Source: Rev. H.A. Jump, The Social Influence of the Moving Picture (New York: Playground and Recreation of America, 1911), pp. 3-4. Reprinted from The Playground, June 1911; originally given as a talk to the People’s Institute, Cooper Union, March 12, 1911, New York City

Text: Recently I was conversing with a group of Persians who are employed in my city. Desirous of ascertaining how American life had impressed them, I put this question: “What was the most amazing experience that came to you after your arrival in the United States?” One man answered, “the subway,” another replied, “a black woman,” a third confessed that it was “the moving picture.” And I observed by the nodding of heads among other members of the company that they were saying amen to his verdict. Further inquiries brought out the fact that practically every one of these foreigners had the habit of going to moving picture shows. One man declared, “I like them because they make me forget that I am tired.” Another said, “I like them because I learn so much from them without knowing the English language.” Evidently the motion picture looms large in the experience of the immigrant.

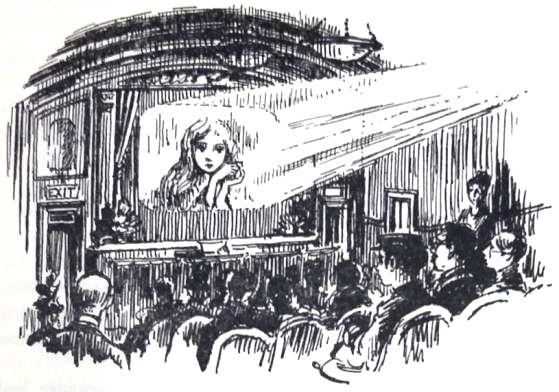

A few weeks ago I visited the public library and had a chat with some three dozen children in the Children’s Room. “How many of you visit the moving picture shows?” I asked, and every hand went up. “What kind of pictures do you like best?” was my second inquiry. “I like the sad pictures,” answered one pale-faced little girl. “I like the kind where they get married,” replied a jolly miss. “I like the pictures of American soldiers marching down the street with the flags going on before,” came from a dark skinned lad. I asked him his name. He answered, “Guiseppi Calderoni.” The librarian of the Children’s Room told of a Hebrew boy who had recently inquired for a story called “The Bride of Lammermoor.” When asked where he had ever heard of that story, he replied, “I saw it in a moving picture show” Before he was through patronizing the library he had read every novel of Sir Walter Scott and much other good fiction besides. Evidently the motion picture occupies a large place in the experience of the school child.

College professors sometimes surprise us by their humanity. One of them told me not long ago that he patronized the moving picture show as often as he could find the time to do so. I expressed surprise, and asked him why he followed up the practice. He answered, “I always find something human in moving pictures; they seem to bring me close to the life of humanity.” Evidently there are educated men who are not above enjoying this marvelous invention.

In short, a new form of entertainment for the people has grown up without our realizing its extent. It appeals to all races, all ages, all stages of culture. In fact, it is one of the most democratic things in modern American life, belonging in a class with the voting booth and the trolley car.

Comments: The Reverend H.A. Jump, of the South Congregational Church, New Britain, Connecticut published the text of a talk he gave in New York City on the new phenomenon of the motion picture show, of which the above are the opening paragraphs. It is a markedly more positive assessment of the effect of motion pictures on audiences, especially the young, than was common from similar social guardians at this time. There had been four film adaptations of Walter Scott’s novel The Bride of Lammermoor, some by way of Donizetti’s opera version, by 1911.

Links: Copy at Hathi Trust