Source: Rudyard Kipling, ‘Mrs Bathurst’, The Windsor Magazine, September 1904, pp. 376-386, collected in Traffics and Discoveries (London: Macmillan, 1904), pp. 337-365

Text: “Yes,” said Pyecroft. “I used to think seein’ and hearin’ was the only regulation aids to ascertainin’ facts, but as we get older we get more accommodatin’. The cylinders work easier, I suppose … Were you in Cape Town last December when Phyllis’s Circus came?”

“No – up country,” said Hooper, a little nettled at the change of venue.

“I ask because they had a new turn of a scientific nature called ‘Home and Friends for a Tickey.'”

“Oh, you mean the cinematograph – the pictures of prize-fights and steamers. I’ve seen ’em up country.”

“Biograph or cinematograph was what I was alludin’ to. London Bridge with the omnibuses – a troopship goin’ to the war – marines on parade at Portsmouth an’ the Plymouth Express arrivin’ at Paddin’ton.”

“Seen ’em all. Seen ’em all,” said Hooper impatiently.

“We Hierophants came in just before Christmas week an’ leaf was easy.”

“I think a man gets fed up with Cape Town quicker than anywhere else on the station. Why, even Durban’s more like Nature. We was there for Christmas,” Pritchard put in.

“Not bein’ a devotee of Indian peeris, as our Doctor said to the Pusser, I can’t exactly say. Phyllis’s was good enough after musketry practice at Mozambique. I couldn’t get off the first two or three nights on account of what you might call an imbroglio with our Torpedo Lieutenant in the submerged flat, where some pride of the West country had sugared up a gyroscope; but I remember Vickery went ashore with our Carpenter Rigdon – old Crocus we called him. As a general rule Crocus never left ‘is ship unless an’ until he was ‘oisted out with a winch, but when ‘e went ‘e would return noddin’ like a lily gemmed with dew. We smothered him down below that night, but the things ‘e said about Vickery as a fittin’ playmate for a Warrant Officer of ‘is cubic capacity, before we got him quiet, was what I should call pointed.”

“I’ve been with Crocus – in the Redoubtable,” said the Sergeant. “He’s a character if there is one.”

“Next night I went into Cape Town with Dawson and Pratt; but just at the door of the Circus I came across Vickery. ‘Oh!’ he says, ‘you’re the man I’m looking for. Come and sit next me. This way to the shillin’ places!’ I went astern at once, protestin’ because tickey seats better suited my so-called finances. ‘Come on,’ says Vickery, ‘I’m payin’.’ Naturally I abandoned Pratt and Dawson in anticipation o’ drinks to match the seats. ‘No,’ he says, when this was ‘inted -‘not now. Not now. As many as you please afterwards, but I want you sober for the occasion.’ I caught ‘is face under a lamp just then, an’ the appearance of it quite cured me of my thirsts. Don’t mistake. It didn’t frighten me. It made me anxious. I can’t tell you what it was like, but that was the effect which it ‘ad on me. If you want to know, it reminded me of those things in bottles in those herbalistic shops at Plymouth – preserved in spirits of wine. White an’ crumply things – previous to birth as you might say.”

“You ‘ave a beastial mind, Pye,” said the Sergeant, relighting his pipe.

“Perhaps. We were in the front row, an’ ‘Home an’ Friends’ came on early. Vickery touched me on the knee when the number went up. ‘If you see anything that strikes you,’ he says, ‘drop me a hint’; then he went on clicking. We saw London Bridge an’ so forth an’ so on, an’ it was most interestin’. I’d never seen it before. You ‘eard a little dynamo like buzzin’, but the pictures were the real thing – alive an’ movin’.”

“I’ve seen ’em,” said Hooper. “Of course they are taken from the very thing itself – you see.”

“Then the Western Mail came in to Paddin’ton on the big magic lantern sheet. First we saw the platform empty an’ the porters standin’ by. Then the engine come in, head on, an’ the women in the front row jumped: she headed so straight. Then the doors opened and the passengers came out and the porters got the luggage – just like life. Only – only when any one came down too far towards us that was watchin’, they walked right out o’ the picture, so to speak. I was ‘ighly interested, I can tell you. So were all of us. I watched an old man with a rug ‘oo’d dropped a book an’ was tryin’ to pick it up, when quite slowly, from be’ind two porters – carryin’ a little reticule an’ lookin’ from side to side – comes out Mrs. Bathurst. There was no mistakin’ the walk in a hundred thousand. She come forward – right forward – she looked out straight at us with that blindish look which Pritch alluded to. She walked on and on till she melted out of – he picture – like – like a shadow jumpin’ over a candle, an’ as she went I ‘eard Dawson in the ticky seats be’ind sing out: ‘Christ! There’s Mrs. B.!'”

Hooper swallowed his spittle and leaned forward intently.

“Vickery touched me on the knee again. He was clickin’ his four false teeth with his jaw down like an enteric at the last kick. ‘Are you sure?’ says he. ‘Sure,’ I says, ‘didn’t you ‘ear Dawson give tongue? Why, it’s the woman herself.’ ‘I was sure before,’ he says, ‘but I brought you to make sure. Will you come again with me to-morrow?’

“‘Willingly,’ I says, ‘it’s like meetin’ old friends.’

“‘Yes,’ he says, openin’ his watch, ‘very like. It will be four-and-twenty hours less four minutes before I see her again. Come and have a drink,’ he says. ‘It may amuse you, but it’s no sort of earthly use to me.’ He went out shaking his head an’ stumblin’ over people’s feet as if he was drunk already. I anticipated a swift drink an’ a speedy return, because I wanted to see the performin’ elephants. Instead o’ which Vickery began to navigate the town at the rate o’ knots, lookin’ in at a bar every three minutes approximate Greenwich time. I’m not a drinkin’ man, though there are those present” – he cocked his unforgettable eye at me–“who may have seen me more or less imbued with the fragrant spirit. None the less, when I drink I like to do it at anchor an’ not at an average speed of eighteen knots on the measured mile. There’s a tank as you might say at the back o’ that big hotel up the hill – what do they call it?”

“The Molteno Reservoir,” I suggested, and Hooper nodded.

“That was his limit o’ drift. We walked there an’ we come down through the Gardens – there was a South-Easter blowin’ – an’ we finished up by the Docks. Then we bore up the road to Salt River, and wherever there was a pub Vickery put in sweatin’. He didn’t look at what he drunk – he didn’t look at the change. He walked an’ he drunk an’ he perspired in rivers. I understood why old Crocus ‘ad come back in the condition ‘e did, because Vickery an’ I ‘ad two an’ a half hours o’ this gipsy manoeuvre an’ when we got back to the station there wasn’t a dry atom on or in me.”

“Did he say anything?” Pritchard asked.

“The sum total of ‘is conversation from 7.45 P.M. till 11.15 P.M. was ‘Let’s have another.’ Thus the mornin’ an’ the evenin’ were the first day, as Scripture says … To abbreviate a lengthy narrative, I went into Cape Town for five consecutive nights with Master Vickery, and in that time I must ‘ave logged about fifty knots over the ground an’ taken in two gallon o’ all the worst spirits south the Equator. The evolution never varied. Two shilling seats for us two; five minutes o’ the pictures, an’ perhaps forty-five seconds o’ Mrs. B. walking down towards us with that blindish look in her eyes an’ the reticule in her hand. Then out walk – and drink till train time.”

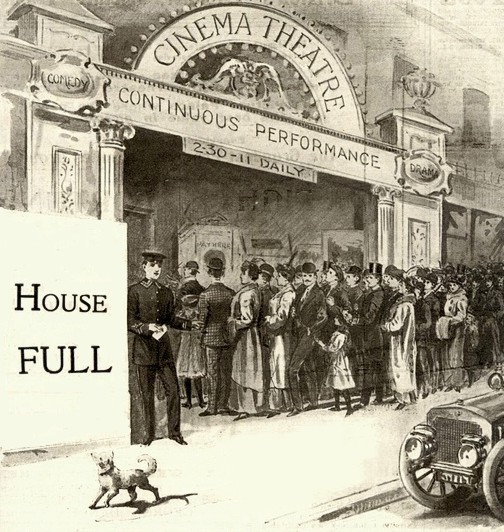

Text: Rudyard Kipling’s mysterious short story ‘Mrs Bathurst’, from which the above is an extract, features a conversation between four men – Pycroft, Pritchard, Hooper and the narrator – the first two of whom are in the navy. Collectively they relate the story of Vickery, a warrant officer, and Mrs Bathurst, with whom it is implied he has had an affair. While stationed in South Africa Vickery sees Mrs Bathurst on an actuality film screened as part of a circus entertainment, something which affects deeply as he returns to see the film several times. Vickery apparently deserts and later a charred corpse matching his description is found, and with it a second, unidentified charred corpse. The significance of the story in an early cinema context is discussed by Tom Gunning in Andrew Shail, Reading the Cinematograph: The Cinema in British Short Fiction 1896-1912 (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2010) which also reproduces Kipling’s text in full. A tickey was a South African threepence coin. ‘Phyllis’s circus’ is a reference to Frank Fillis, a South African showman whose ‘Savage South Africa’ troupe was filmed when it visited Britain in 1899-1900. The story suggests that the film element of Fillis’ show lasted for five minutes, just before the elephants. As Gunning points out, the reference to the “dynamo like buzzin'” not only suggests the sound of the projector but implies that there was no musical accompaniment. The film itself bears a strong affinity with the many train arrival films common in the 1890s.