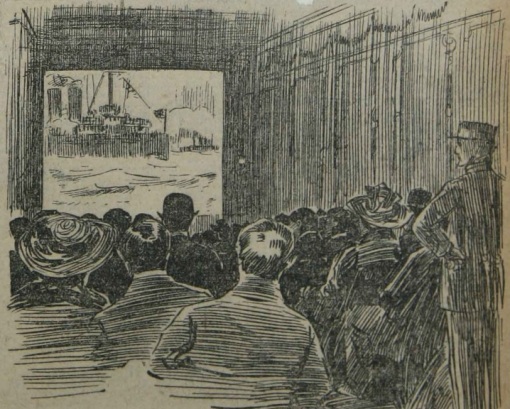

Illustration accompanying the original article

Source: ‘The Picture-Palaces of London’, The Daily Chronicle, 9 April 1910

Text: The Picture-Palaces of London. Have They Comes to Stay?

Pricked out in electric lights, on an imposing brand new structure of white stucco, you read the words “Cinematograph Theatre.” You wonder where the thing has come from. Like Aladdin’s Palace, it seems to have sprung up in a single night. On yesterday there was a block of old houses on that very spot. You remember looking in a the greengrocer’s window as you sauntered home to dinner, wondering what kind of fruit the children would like.

Well, no, it could not have been yesterday, but it was certainly the week before last!

A few weeks later the white stucco erection appears to have budded. There are two of the now, side by side. The matter is worth further enquiry, so you cross over, and read the “bill of fare” at either door. The rival attendants, gorgeously arrayed, glance at you with enticing eyes, but you regard not their mute entreaties. Then you are probably taken by surprise. The charm of the things catches you. Perhaps it is best set down as a free-and-easiness. Go when you will, after the door is opened, you are never late; never in anxiety over a seat. The show goes on continuously. There is a set of pictures for the day – six perhaps, or eight – and if you miss numbers one and two, why, you will see them for certain after number eight.

Entertainment Ad Lib.

The set may last an hour, to an hour and a half, but you need not go out at that time unless you have a mind to. You may sit still, if you choose, and see the whole set over again. I dare say you won’t, unless it is pouring wet outside, and you have forgotten your umbrella, but it is something to know that you can.

The cinematograph theatre fills a gap in our scheme of amusement. It may be a small gap, but still it was there, and now it is filled. It catches the leakage from the theatres and halls, the unfortunately who are sent sorrowfully away by the unwelcome announcement of “House full.”

It gives the tired sightseer an hour’s respite from the noise and fatigue of the streets, and in some cases it dangles the tempting bait of “afternoon tea[“] gratis before this type of prospective patron. To the regular theatre it stands in the same relationship as a “snack” does to a formal luncheon. It is the resource of the man with only an hour to spare, the lady who doesn’t like to be out late, the girl whose papa doesn’t approve of theatres, the little boy who must be in bed at six, the hospital nurse who only has two hours off duty, and the family party from the provinces, whose train starts at ten sharp.

Oh, and one must not forget the lovers! Humble lovers, perhaps, with a few shillings to spare. one sees them often in the sixpenny seats, holding hands in the friendly dark. They watch the films go spinning on, with absent eyes and beatific smiles. They haven’t come there for the show, but to find a corner to sit in, out of the wet. One can’t always go round and round the Inner Circle with a penny ticket without catching the eye of the cute conductor!

The Aristocratic Sixpence.

There are differences in the quality of these as of all other types of amusement. There are the second-raters in the outlying streets, just beyond the radius of West-end style. The modest sum of threepence will gain you admittance here, and if you indulge yourself to the tune of sixpence you are “a swell.” The pictures are usually quite up to the average, but the environment is not. The dark is not friendly, but apprehensive. One is suspicious of one’s neighbour, and keeps a tight clutch on one’s belongings. There is every prospect of carrying away with you less than you ought, and more than you bargained for. Reminiscences of the place are forced upon you next day by the odour of stale and indifferent tobacco that clings to your clothes. As you near the vicinity of Oxford-street there is a decided attempt at luxury in the internal appointments of the “Palaces.” The goods are not all in the shop window. Decidedly, too, the “orchestra” plays better. It consists usually of a girl with a piano, the latter very much at her mercy. In some of the theatres visited by the writer, it would be only charitable to suppose that the lady pianist had fallen a victim to the prevalent disease newly christened by a London daily as “The Hump.” She played in spasms, with a reckless disregard of time and tune, and an obvious idea that her function was merely to drown out the silence.

In the West they have changed all that, and, incidentally, the prices have gone up. We may now pay two shillings for a “fauteuil” (which is a horrid, awkward word to spell, and means exactly the same as seat, anyway!). Along with the fauteuil we have the advantage of being shone upon by rose-shaded electric lights, vastly improving to the complexion, and of feasting our eyes on the artistic decorations of the walls when we tire of the pictures.

People do not laugh so boisterously here as they do in the north and east. At most they chuckle. On the whole, there is a remarkable absence of all kinds of noise in these cinematograph theatres. Applause seems to be a thing unknown. It is a relief to hear the voice of a child imperiously demanding, as the name of the film appears, “Read it, mother. Read it quick!”

Child’s Living Picture Book.

The little folks are mostly to be found at the afternoon performances. It must all seem a kind of glorified picture book to them. How they roar over the man who knocks down everything, or the fat old lady pursued by some strange fatality, who is knocked down by everybody! They have a wonderful aptitude, too, for following the “story” in some of the more ambitious pictures. The kidnapped child is one of their favourites. “Did they find him, mother? Are you sure?” a little lad asks in a tearful voice, to the kindly amusement of all who sit near by. The tragic subjects find favour with young ladies, one fancies, and indeed they are sometimes admirably conceived – real dramas, in which the words are hardly missed. The marvellous power of facial expression to convey an emotion in all its subtle shades is brought home to the mind with striking force by the intense interest one feels in these “mimed” plays. Of course it is hard to forget that the pictures are “faked.” One could never for a moment admit the possibility of pictorial drama affecting the taste for the drama of the regular stage. Too much talk may be bad, as was instanced in a recent much-criticised production, but no talk at all is the worse evil of the two.

Perhaps most successful of all are the travel pictures, where the scenery is absolutely realistic, and the sense of motion admirably conveyed. No “book of views,” however beautiful, can fascinate as this moving panorama does. It is as good as a holiday – and somewhat cheaper!

Have the pictures come to stay? Yes, they have filled a gap. It will be long before anything more novel or more entertaining appears to fit that precise niche in the House of Pleasure.

Comment: The inner Circle refers to a London underground train line.