Source: Charles Dickens, ‘Some Account of an Extraordinary Traveller’, Household Words, 20 April 1850, pp. 73-77

Text: No longer ago than this Easter time last past, we became acquainted with the subject of the present notice. Our knowledge of him is not by any means an intimate one, and is only of a public nature. We have never interchanged any conversation with him, except on one occasion when he asked us to have the goodness to take off our hat, to which we replied ‘Certainly.’

Mr. Booley was born (we believe) in Rood Lane, in the City of London. He is now a gentleman advanced in life, and has for some years resided in the neighbourhood of Islington. His father was a wholesale grocer (perhaps) and he was (possibly) in the same way of business; or he may, at an early age, have become a clerk in the Bank of England or in a private hank, or in the India House. It will he observed that we make no pretence of having any information in reference to the private history of this remarkable man, and that our account of it must be received as rather speculative than authentic.

In person Mr. Booley is below the middle size, and corpulent. His countenance is florid, he is perfectly bald, and soon hot; and there is a composure in his gait and manner, calculated to impress a stranger with the idea of his being, on the whole, an unwieldy man. It is only in his eye that the adventurous character of Mr. Booley is seen to shine. It is a moist, bright eye, of a cheerful expression, and indicative of keen and eager curiosity.

It was not until late in life that Mr. Booley conceived the idea of entering on the extraordinary amount of travel be has since accomplished. He had attained the age of sixty-five before be left England for the first time. In all the immense journeys he has since performed, he has never laid aside the English dress, nor departed in the slightest degree from English customs. Neither does he speak a word of any language but his own.

Mr. Booley’s powers of endurance are wonderful. All climates are alike to him. Nothing exhausts him; no alternations of heat and cold appear to have the least effect upon his hardy frame. His capacity of travelling, day and night, for thousands of miles, has never been approached by any traveller of whom we have any knowledge through the help of books. An intelligent Englishman may have occasionally pointed out to him objects and scenes of interest; but otherwise he has travelled alone and unattended. Though remarkable for personal cleanliness, he has carried no luggage; and his diet has been of the simplest kind. He has often found a biscuit, or a bun, sufficient for his support over a vast tract of country. Frequently he has travelled hundreds of miles, fasting, without the least abatement of his natural spirits. It says much for the Total Abstinence cause, that Mr. Booley has never had recourse to the artificial stimulus of alcohol, to sustain him under his fatigues.

His first departure from the sedentary and monotonous life he had hitherto led, strikingly exemplifies, we think, the energetic character, long suppressed by that unchanging routine. Without any communication with any member of his family – Mr. Booley has never been married, but has many relations – without announcing his intention to his solicitor, or banker, or any person entrusted with the management of his affairs, he closed the door of his house behind him at one o’clock in the afternoon of a certain day, and immediately proceeded to New Orleans, in the United States of America.

His intention was to ascend the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, to the base of the Rocky Mountains. Taking his passage in a steamboat without loss of time, he was soon upon the bosom of the Father of Waters, as the Indians call the mighty stream which, night and day, is always carrying huge instalments of the vast continent of the New World down into the sea.

Mr. Booley found it singularly interesting to observe the various stages of civilisation obtaining on the banks of these mighty rivers. Leaving the luxury and brightness of New Orleans – a somewhat feverish luxury and brightness, he observed, as if the swampy soil were too much enriched in the hot sun with the bodies of dead slaves – and passing various towns in every stage of progress, it was very curious to observe the changes of civilisation and of vegetation too. Here, while the doomed negro race were working in the plantations, while the republican overseer looked on, whip in hand, tropical trees were growing, beautiful flowers in bloom; the alligator, with his horribly sly face, and his jaws like two great saws, was basking on the mud; and the strange moss of the country was hanging in wreaths and garlands on the trees, like votive offerings. A little farther towards the west, and the trees and flowers were changed, the moss was gone, younger infant towns were rising, forests were slowly disappearing, and the trees, obliged to aid in the destruction of their kind, fed the heavily-breathing monster that came clanking up those solitudes laden with the pioneers of the advancing human army. The river itself, that moving highway, showed him every kind of floating contrivance, from the lumbering flat-bottomed boat, and the raft of logs, upward to the steamboat, and downward to the poor Indian’s frail canoe. A winding thread through the enormous range of country, unrolling itself before the wanderer like the magic skein in the story, he saw it tracked by wanderers of every kind, roaming from the more settled world, to those first nests of men. The floating theatre, dwelling-house, hotel, museum, shop; the floating mechanism for screwing the trunks of mighty trees out of the mud, like antediluvian teeth; the rapidly-flowing river, mid the blazing woods; he left them all behind – town, city, and log-cabin, too; and floated up into the prairies and savannahs, among the deserted lodges of tribes of savages, and among their dead, lying alone on little wooden stages with their stark faces upward towards the sky. Among the blazing grass, and herds of buffaloes and wild horses, and among the wigwams of the fast-declining Indians, he began to consider how, in the eternal current. of progress setting across this globe in one unchangeable direction, like the unseen agency that points the needle to the Pole, the Chiefs who only dance the dances of their fathers, and will never have a new figure for a new tune, and the Medicine men who know no Medicine but what was Medicine a hundred years ago, must be surely and inevitably swept from the earth, whether they be Choctawas, Maudans, Britons, Austrians, or Chinese.

He was struck, too, by the reflection that savage nature was not by any means such a fine and noble spectacle as some delight to represent it. He found it a poor, greasy, paint-plastered miserable thing enough; but a very little way above the beasts in most respects; in many customs a long way below them. It occurred to him that the ‘Big Bird,’ or the ‘Blue Fish,’ or any of the other Braves, was but a troublesome braggart after all; making a mighty whooping and halloaing about nothing particular, doing very little for science, not much more than the monkeys for art, scarcely anything worth mentioning for letters, and not often making the world greatly better than he found it. Civilisation, Mr. Booley concluded, was, on the whole, with all its blemishes, a more imposing sight, and a far better thing to stand by.

Mr. Booley’s observations of the celestial bodies, on this voyage, were principally confined to the discovery of the alarming fact that light had altogether departed from the moon; which presented the appearance of a white dinner-plate The clouds, too, conducted themselves in an extraordinary manner, and assumed the most eccentric forms, while the sun rose and set in a very reckless way. On his return to his native country, however, he had the satisfaction of finding all these things as usual.

It might have been expected that at his advanced age, retired from the active duties of life, blessed with a competency, and happy in the affections of his numerous relations, Mr. Booley would now have settled himself down, to muse, for the remainder of his days, over the new stock of experience thus acquired. But travel had whetted, not satisfied, his appetite; and remembering that he had not seen the Ohio River, except at the point of its junction with the Mississippi, he returned to the United States, after a short interval of repose, and appearing suddenly at Cincinnati, the queen City of the West, traversed the clear waters of the Ohio to its Falls. In this expedition he had the pleasure of encountering a party of intelligent workmen from Birmingham who were making the same tour. Also his nephew Septimus, aged only thirteen. This intrepid boy had started from Peckham, in the old country, with two and sixpence sterling in his pocket; and had, when he encountered his uncle at a point of the Ohio River, called Snaggy Bar, still one shilling of that sum remaining!

Again at home, Mr. Booley was so pressed by his appetite for knowledge as to remain at home only one day. At the expiration of that short period, he actually started for New Zealand.

It is almost incredible that a man in Mr. Booley’s station of life, however adventurous his nature, and however few his artificial wants, should cast himself on a voyage of thirteen thousand miles from Great Britain with no other outfit than his watch and purse, and no arms but his walking-stick. We are, however, assured on the best authority, that thus he made the passage out, and thus appeared, in the act of wiping his smoking head with his pocket-handkerchief, at the entrance to Port Nicholson in Cook’s Straits: with the very spot within his range of vision, where his illustrious predecessor, Captain Cook, so unhappily slain at Otaheite, once anchored.

After contemplating the swarms of cattle maintained on the hills in this neighbourhood, and always to be found by the stockmen when they are wanted, though nobody takes any care of them – which Mr. Booley considered the more remarkable, as their natural objection to be killed might be supposed to be augmented by the beauty of the climate – Mr. Booley proceeded to the town of Wellington. Having minutely examined it in every point, and made himself perfect master of the whole natural history and process of manufacture of the flax-plant, with its splendid yellow blossoms, he repaired to a Native Pa, which, unlike the Native Pa to which he was accustomed, he found to be a town, and not a parent. Here he observed a chief with a long spear, making every demonstration of spitting a visitor, but really giving him the Maori or welcome – a word Mr. Booley is inclined to derive from the known hospitality of our English Mayors – and here also he observed some Europeans rubbing noses, by way of shaking hands, with the aboriginal inhabitants. After participating in an affray between the natives and the English soldiers, in which the former were defeated with great loss, he plunged into the Bush, and there camped out for some months, until he had made a survey of the whole country.

While leading this wild life, encamped by night near a stream for the convenience of water in a Ware, or lint, built open in the front, with a roof sloping backward to the ground, and made of poles, covered and enclosed with bark or fern, it was Mr. Booley’s singular fortune to encounter Miss Creeble, of The Misses Creeble’s Boarding and Day Establishment for Young Ladies, Kennington Oval, who, accompanied by three of her young ladies in search of information, had achieved this marvellous journey, and was then also in the Bush. Miss Creeble, having very unsettled opinions on the subject of gunpowder, was afraid that it entered into the composition of the fire before the tent, and that something would presently blow up or go off. Mr. Booley, as a more experienced traveller, assuring her that there was no danger; and calming the fears of the young ladies, an acquaintance commenced between them. They accomplished the rest of their travels in New Zealand together, and the best understanding prevailed among the little party. They took notice of the trees, as the Kaikatea, the Kauri, the Ruta, the Pukatea, the Hinau, and the Tanakaka – names which Miss Creeble had a bland relish in pronouncing. They admired the beautiful, aborescent, palm-like fern, abounding everywhere, and frequently exceeding thirty feet in height. They wondered at the curious owl, who is supposed to demanded ‘More Pork!’ wherever he flies, and whom Miss Creeble termed ‘an admonition of Nature against greediness!’ And they contemplated some very rampant natives of cannibal propensities. After many pleasing and instructive vicissitudes, they returned to England in company, where the ladies were safely put into a hackney cabriolet by Mr. Booley, in Leicester Square, London.

And now, indeed, it might have been imagined that that roving spirit, tired of rambling about the world, would have settled down at home in peace and honour. Not so. After repairing to the tubular bridge across the Menai Straits, and accompanying Her Majesty on her visit to Ireland (which he characterised as ‘a magnificent Exhibition’), Mr. Booley, with his usual absence of preparation, departed for Australia.

Here again, he lived out in the Bush, passing his time chiefly among the working-gangs of convicts who were carrying timber. He was much impressed by the ferocious mastiffs chained to barrels, who assist the sentries in keeping guard over those misdoers. But he observed that the atmosphere in this part of the world, unlike the descriptions he had read of it, was extremely thick, and that objects were misty, and difficult to be discerned. From a certain unsteadiness and trembling, too, which he frequently remarked on the face of Nature, he was led to conclude that this part of the globe was subject to convulsive heavings and earthquakes. This caused him to return with some precipitation.

Again at home, and probably reflecting that the countries he had hitherto visited were new in the history of man, this extraordinary traveller resolved to proceed up the Nile to the second cataract. At the next performance of the great ceremony of ‘opening the Nile,’ at Cairo, Mr. Booley was present.

Along that wonderful river, associated with such stupendous fables, and with a history more prodigious than any fancy of man, in its vast and gorgeous facts; among temples, palaces, pyramids, colossal statues, crocodiles, tombs, obelisks, mummies, sand and ruin; he proceeded, like an opium-eater in a mighty dream. Thebes rose before him. An avenue of two hundred sphinxes, with not a head among them, – one of six or eight, or ten such avenues, all leading to a common centre – conducted to the Temple of Carnak: its walls, eighty feet high and twenty-five feet thick, a mile and three-quarters in circumference; the interior of its tremendous hall, occupying an area of forty-seven thousand square feet, large enough to hold four great Christian churches, and yet not more than one-seventh part of the entire ruin. Obelisks he saw, thousands of years of age, as sharp as if the chisel had cut their edges yesterday: colossal statues fifty-two feet high, with ‘little’ fingers five feet and a half long; a very world of ruins, that were marvellous old ruins in the days of Herodotus; tombs cut high up in the rock, where European travellers live solitary, as in stony crow’s nests, burning mummied Thebans, gentle and simple – of the dried blood-royal maybe – for their daily fuel, and making articles of furniture of their dusty coffins. Upon the walls of temples, in colours fresh and bright as those of yesterday, he read the conquests of great Egyptian monarchs: upon the tombs of humbler people in the same blooming symbols, he saw their ancient way of working at their trades, of riding, driving, feasting, playing games; of marrying and burying, and performing on instruments, and singing songs, and healing by the power of animal magnetism, and performing all the occupations of life. He visited the quarries of Silsileh, whence nearly all the red stone used by the ancient Egyptian architects and sculptors came; and there beheld enormous singled-stoned colossal figures, nearly finished – redly snowed up, as it were, and trying hard to break out – waiting for the finishing touches, never to be given by the mummied hands of thousands of years ago. In front of the temple of Abou Simbel, he saw gigantic figures sixty feet in height and twenty one across the shoulders, dwarfing live men on camels down to pigmies. Elsewhere he beheld complacent monsters tumbled down like ill-used Dolls of a Titanic make, and staring with stupid benignity at the arid earth whereon their huge faces rested. His last look of that amazing land was at the Great Sphinx, buried in the sand – sand in its eyes, sand in its ears, sand drifted on its broken nose, sand lodging, feet deep, in the ledges of its head – struggling out of a wide sea of sand, as if to look hopelessly forth for the ancient glories once surrounding it.

In this expedition, Mr. Booley acquired some curious information in reference to the language of hieroglyphics. He encountered the Simoon in the Desert, and lay down, with the rest of his caravan until it had passed over. He also beheld on the horizon some of those stalking pillars of sand, apparently reaching from earth to heaven, which, with the red sun shining through them, so terrified the Arabs attendant on Bruce, that they fell prostrate, crying that the Day of Judgment was come. More Copts, Turks, Arabs, Fellahs, Bedouins, Mosques, Mamelukes, and Moosulmen he saw, than we have space to tell. His days were all Arabian Nights, and he saw wonders without end.

This might have satiated any ordinary man, for a time at least. But Mr. Booley, being no ordinary man, within twenty-four hours of his arrival at home was making the overland journey to India.

He has emphatically described this, as ‘a beautiful piece of scenery,’ and ‘a perfect picture.’ The appearance of Malta and Gibraltar he can never sufficiently commend. In crossing the desert from Grand Cairo to Suez he was particularly struck by the undulations of the Sandscape (he preferred that word to Landscape, as more expressive of the region), and by the incident of beholding a caravan upon its line of march; a spectacle which in the remembrance always affords him the utmost pleasure. Of the stations on the desert, and the cinnamon gardens of Ceylon, he likewise entertains a lively recollection. Calcutta he praises also; though he has been heard to observe that the British military at that seat of Government were not as well proportioned as he could desire the soldiers of his country to be; and that the breed of horses there in use was susceptible of some improvement.

Once more in his native land, with the vigour of his constitution unimpaired by the many toils and fatigues he had encountered, what had Mr. Booley now to do, but, full of years and honour, to recline upon the grateful appreciation of his Queen and country, always eager to distinguish peaceful merit? What had he now to do, but to receive the decoration ever ready to be bestowed, in England, on men deservedly distinguished, and to take his place among the best? He had this to do. He had yet to achieve the most astonishing enterprise for which he was reserved. In all the countries he had yet visited, he had seen no frost and snow. He resolved to make a voyage to the ice-bound arctic regions.

In pursuance of this surprising determination, Mr. Booley accompanied the expedition under Sir James Boss, consisting of Her Majesty’s ships the Enterprise and Investigator, which sailed from the River Thames on the 12th of May 1848, and which, on the 11th of September, entered Port Leopold Harbour.

In this inhospitable region, surrounded by eternal ice, cheered by no glimpse of the sun, shrouded in gloom and darkness, Mr. Booley passed the entire winter. The ships were covered in, and fortified all round with walls of ice and snow; the masts were frozen up; hoar frost settled on the yards, tops, shrouds, stays, and rigging: around, in every direction, lay an interminable waste, on which only the bright stars, the yellow moon, and the vivid Aurora Borealis looked, by night or day.

And yet the desolate sublimity of this astounding spectacle was broken in a pleasant and surprising manner. In the remote solitude to which he had penetrated, Mr. Booley (who saw no Esquimaux during his stay, though he looked for them in every direction) had the happiness of encountering two Scotch gardeners; several English compositors, accompanied by their wives; three brass-founders from the neighbourhood of Long Acre, London; two coach-painters, a gold-beater and his only daughter, by trade a staymaker; and several other working-people from sundry parts of Great Britain who had conceived the extraordinary idea of ‘holiday-making’ in the frozen wilderness. Hither, too, had Miss Creeble and her three young ladies penetrated; the latter attired in braided peacoats of a comparatively light maternal; and Miss Creeble defended from the inclemency of a Polar Winter by no other outer garment than a wadded Polka-jacket. He found this courageous lady in the net of explaining, to the youthful sharers of her toils, the various phases of nature by which they were surrounded. Her explanations were principally wrong, but her intentions always admirable.

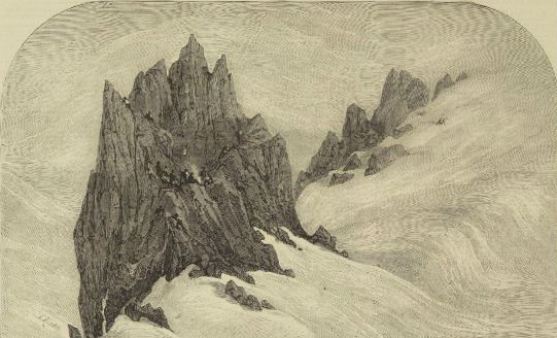

Cheered by the society of these fellow-adventurers, Mr. Booley slowly glided on into the summer season. And now, at midnight, all was bright and shining. Mountains of ice, wedged and broken into the strangest forms – jagged points, spires, pinnacles, pyramids, turrets, columns in endless succession and in infinite variety, flashing and sparkling with ten thousand hues, as though the treasures of the earth were frozen up in all that water – appeared on every side. Masses of ice, floating and driving hither and thither, menaced the hardy voyagers with destruction; and threatened to crush their strong ships, like nutshells. But, below those ships was clear sea-water, now; the fortifying walls were gone; the yards, tops, shrouds and rigging, free from that hoary rust of long inaction, showed like themselves again; and the sails, bursting from the masts, like foliage which the welcome sun at length developed, spread themselves to the wind, and wafted the travellers away.

In the short interval that has elapsed since his safe return to the land of his birth, Mr. Booley has decided on no new expedition; but he feels that he will yet be called upon to undertake one, perhaps of greater magnitude than any he has achieved, and frequently remarks, in his own easy way, that he wonders where the deuce he will he taken to next! Possessed of good health and good spirits, with powers unimpaired by all he has gone through, mid with an increase of appetite still growing with what it feeds on, what may not be expected yet from this extraordinary man!

It was only at the close of Easter week that, sitting in an armchair, at a private club called the Social Oysters, assembling at Highbury Barn, where he is much respected, this indefatigable traveller expressed himself in the following terms:

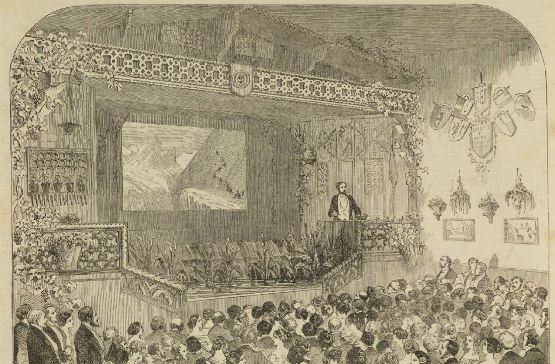

‘It is very gratifying to me,’ said he, ‘to have seen so much at my time of life, and to have acquired a knowledge of the countries I have visited, which I could not have derived from books alone. When I was a boy, such travelling would have been impossible, as the gigantic-moving-panorama or diorama mode of conveyance, which I have principally adopted (all my modes of conveyance have been pictorial), had then not been attempted. It is a delightful characteristic of these times, that new and cheap means are continually being devised for conveying the results of actual experience to those who are unable to obtain such experiences for themselves: and to bring them within the reach of the people – emphatically of the people; for it is they at large who are addressed in these endeavours, and not exclusive audiences. Hence,’ said Mr. Booley, ‘even if I see a run on an idea, like the panorama one, it awakens no ill-humour within me, but gives me pleasant thoughts. Some of the best results of actual travel are suggested by such means to those whose lot it is to stay at home. New worlds open out to them, beyond their little worlds, and widen their range of reflection, information, sympathy, and interest. The more man knows of man, the better for the common brotherhood among us all. I shall, therefore,’ said Mr. Booley, now propose to the Social Oysters, the healths of Mr. Banvard, Mr. Brees, Mr. Phillips, Mr. Allen, Mr. Prout, Messrs. Bonomi, Fahey, and Warren, Mr. Thomas Grieve, and Mr. Burford. Long life to them all, and more power to their pencils?’

The Social Oysters having drunk this toast with acclamation, Mr. Booley proceeded to entertain them with anecdotes of his travels. This he is in the habit of doing after they have feasted together, according to the manner of Sinbad the Sailor – except that he does not bestow upon the Social Oysters the munificent reward of one hundred sequins per night, for listening.

Comments: Charles Dickens (1812-1870) was a British novelist and journalist. Household Words was a weekly magazine that Dickens edited and contributed to. Mr Booley was an elderly gentleman character created by Dickens who features in three Household Words pieces (a second was on Mr Booley’s experience of the Lord Mayor’s Show). Dickens was an enthusiastic viewers of panoramas and dioramas (see https://picturegoing.com/?p=4387). Those whose health is proposed at the end of the article are panorama showmen and artists, including John Banvard, Samuel Charles Brees, John Skinner Prout, Joseph Bonomi, James Fahey, Henry Warren, Thomas Grieve and Robert Burford.

Links: Available at Dickens Journals Online