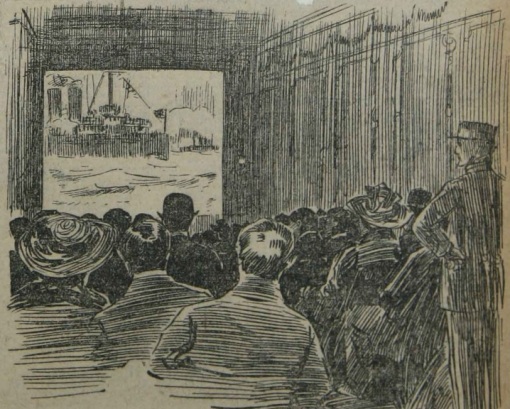

‘They were permitted to drink deep of oblivion of all the trouble of the world’. The illustration by Wladyslaw T. Benda (and its caption) accompanied Mary Heaton Vorse’s original article for Outlook magazine

Source: Mary Heaton Vorse, ‘Some Picture Show Audiences’, Outlook 98, 24 June 1911, pp. 441-447

Text: One rainy night in a little Tuscan town I went to a moving-picture show. It was market-day; the little hall was full of men in their great Italian cloaks. They had come in from small isolated hamlets, from tiny fortified towns perched on the tops of distant hills to which no road led, but only a salita. I remembered that there was in the evening’s entertainment a balloon race, and a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and a mad comic piece that included a rush with a baby-carriage through the boulevards of Paris; and there was a drama, ‘The Vendetta,’ which had for its background the beautiful olive terraces of Italy.

I had gone, as they had, to see pictures, but in the end I saw only them, because it seemed to me that what had happened was a latter-day miracle. By an ingenious invention all the wonderful things that happened in the diverse world outside their simple lives could come to them. They had no pictures or papers; few of them could read; and yet they sat there at home and watching the inflating of great balloons and saw them rise and soar and go away into the blue, and watched again the strange Oriental crowd walking through the holy streets of Jerusalem. It is hard to understand what a sudden widening of their horizon that meant for them. It is the door of escape, for a few cents, from the realities of life.

It is drama, and it is travel, and it is even beauty, all in one. A wonderful things it is, and to know how wonderful I suppose you must be poor and have in your life no books and no pictures and no means of travel or seeing beautiful places, and almost no amusements of any kind; perhaps your only door of escape or only means of forgetfulness more drink that is good for you. Then you will know what a moving-picture show really means, although you will probably not be able to put it into words.

We talk a good deal about the censorship of picture shows, and pass city ordinances to keep the young from being corrupted by them: and this is all very well, because a great amusement of the people ought to be kept clean and sweet; but at the same time this discussion has left a sort of feeling in the minds of people who do not need to go to the picture show that it is a doubtful sort of a place, where young girls and mean scrape undesirable acquaintances, and where the prowler lies in wait for the unwary, and where suggestive films of crime and passion are invariably displayed. But I think that this is an unjust idea, and that any one who will take the trouble to amuse himself with the picture show audiences for an afternoon or two will see why it is that the making of films has become a great industry, why it is that the picture show has driven out the vaudeville and the melodrama.

You cannot go to any one of the picture shows in New York without having a series of touching little adventures with the people who sit near you, without overhearing chance words of a naiveté and appreciation that make you bless the living picture book that has brought so much into the lives of the people who work.

Houston Street, on the East Side, of an afternoon is always more crowded than Broadway. Push=carts line the street. The faces that you see are almost all Jewish – Jews of many types; swarthy little men, most of them, looking under-sized according to the Anglo-Saxon standard. Here and there a deep-chested mother of Israel sails along, majestic in shietel and shawl. These are the toilers – garment-makers, a great many of them – people who work ‘by pants,’ as they say. A long and terrible workday they have to keep body and soul together. Their distractions are the streets, and the bargaining off the push-carts, and the show. For a continual trickle of people of people detaches itself from the crowded streets and goes into the good-sized hall; and around the entrance too, wait little boys – eager-eyed little boys – with their tickets in their hands, trying to decoy those who enter into taking them in with them as guardians, because the city ordinances do not allow a child under sixteen to go in unaccompanied by an older person.

In the half-light the faces of the audience detach themselves into little pallid ovals, and, as you will always find in the city, it is an audience largely composed of men.

Behind us sat a woman with her escort. So rapt and entranced was she with what was happening on the stage that her voice accompanied all that happened – a little unconscious and lilting obbligato. It was the voice of a person unconscious that she spoke – speaking from the depths of emotion; a low voice, but perfectly clear, and the unconsciously spoken words dropped with the sweetness of running water. She spoke in German. One would judge her to be from Austria. She herself was lovely in person and young, level-browed and clear-eyed: a beneficent and lovely woman one guessed her to be. And she had never seen Indians before; perhaps never heard of them.

The drama being enacted was the rescue from the bear pit of Yellow Wing, the lovely Indian Maiden, by Dick the Trapper; his capture by the tribe, his escape with the connivance of Yellow Wing, who goes to warn him in his log house, their siege by the Indians, and final rescue by a splendid charge of the United States cavalry; these one saw riding with splendid abandon over hill and dale, and the marriage then and there of Yellow Wing and Dick by the gallant chaplain. A guileless and sentimental dime novel, most ingeniously performed; a work of art; beautiful, too, because one had glimpses of stately forests, sunlight sifting through leaves, wild, dancing forms of Indians, the beautiful swift rushing of horses. One must have had a heart of stone not to follow the adventures of Yellow Wing and Dick the Trapper with passionate interest.

But to the woman behind it was reality at its highest. She was there in a fabled country full of painted savages. The rapidly unfolding drama was to her no make-believe arrangement ingeniously fitted together by actors and picture-makers. It had happened; it was happening for her now.

‘Oh!’ she murmured. ‘That wild and terrible people! Oh boy, take care, take care! Those wild and awful people will egt you!’ ‘Das wildes und grausames Volk,’ she called them. ‘Now – now – she comes to save her beloved!’ This as Yellow Wing hears the chief plotting an attack on Dick the Trapper, and flies fleet-foot through the forest. ‘Surely, surely, she will save her beloved!’ It was almost a prayer; in the woman’s simple mind there was no foregone conclusion of a happy ending. She saw no step ahead, since she lived in the present moment so intensely.

When Yellow Wing and Dick were besieged within and Dick’s hand was wounded –

‘The poor child! how can she bear it? To see the geliebte wounded before one’s very eyes!’

And when the cavalry thundered through the forest –

‘God give that they arrive swiftly – to be in time they must arrive swiftly!’ she exclaimed to herself.

Outside the iron city roared: before the door of the show the push-cart vendors bargained and trafficked with customers. Who is the audience remembered it? They had found the door of escape. For the moment they were in the depths of the forest following the loves of Yellow Wing and Dick. The woman’s voice, so like the voice of a spirit talking to itself, unconscious of time and place, was their voice. There they were; a strange company of aliens – Jews, almost all; haggard and battered and bearded men, young girls with their beaus, spruce and dapper youngsters beginning to make their way. In that humble playhouse one ran the gamut of the East Side. The American-born sat next to the emigrant who arrived but a week before. A strange and romantic people cast into the welter of the terrible city of New York, each of them with the overwhelming problem of battling with strange conditions and an alien civilization. And for the moment they were permitted to drink deep of oblivion of all the trouble in the world. Life holds some compensation, after all. The keener your intellectual capacity, the higher your artistic sensibilities are developed, just so much more difficult is it to find this total forgetfulness – a thing that for the spirit is a life-giving as sleep.

And all through the afternoon and evening this company of tired workers, overburdened men and women, fills the little halls scattered throughout the city and throughout the land.

There are motion-picture shows in New York that are as intensely local to the audience as to the audience of a Tuscan hill town. Down on Bleecker Street is the Church of Our Lady of Pompeii. Here women, on their way to work or to their brief marketing, drop in to say their prayers before their favourite saints in exactly the same fashion as though it were a little church in their own parish. Towards evening women with their brood of children go in: the children frolic and play subdued tag in the aisles, for church with them is an every-day affair, not a starched-up matter of Sunday only. Then, prayers finished, you may see a mother sorting out her own babies and moving on serenely to the picture show down the road – prayers first and amusement afterwards, after the good old Latin fashion.

It is on Saturday nights down here that the picture show reaches its high moment. The whole neighborhood seems to be waiting for a chance to go in. Every woman has a baby in her arms and at least two children clinging to her skirts. Indeed, so universal is this custom that a woman who goes there unaccompanied by a baby feels out of place, as if she were not properly dressed. A baby seems as much a matter-of-course adjunct to one’s toilet on Bleecker Street as a picture hat would be on Broadway.

every one seems to know everyone else. As a new woman joins the throng other women cry out to her, gayly:

‘Ah, good-evening, Concetta. How is Giuseppe’s tooth?’

‘Through at last,’ she answers. ‘And where are your twins?’

The first woman makes a gesture indicating that they are somewhere swallowed up in the crowd.

This talk all goes on in good north Italian, for the people on Bleecker Street are the Tuscan colony. There are many from Venice also, and from Milan and from Genoa. The South Italian lives on the East Side.

Then, as the crowd becomes denser, as the moment for the show approaches, they sway together, pushed on by those on the outskirts of the crowd. And yet everyone is good-tempered. It is –

‘Not so hard there, boy!’

‘Mind for the baby!’

‘Look out!’

Though indeed it doesn’t seem any place for a baby at all, and much less so for the youngsters who aren’t in their mothers’ arms but are perilously engulfed in the swaying mass of people. But the situation is saved by Latin good temper and the fact that every one is out for a holiday.

By the time one has stood in this crowd twenty minutes and talked with the women and babies, one had made friends, given an account of oneself, told how it was one happened to speak a little Italian, and where it was in Italy one had lived, for all the world as one gives an account of one’s self when travelling through Italian hamlets. One answers the questions that Italian women love to ask:

‘Are you married?’

‘Have you children?’

‘Then why aren’t they at the picture show with you?’

This audience was an amused, and an amusing audience, ready to laugh, ready to applaud. The young man next me had an ethical point of view. He was a serious, dark-haired fellow, and took his moving pictures seriously. He and his companion argued the case of the cowboy who stole because of his sick wife.

‘He shouldn’t have done it,’ he maintained.

‘His wife was dying, poveretta,’ his companion defended.

‘His wife was a nice girl,” said the serious young man. ‘You saw for yourself how nice a girl. One has but to look at her to see how good she is.’ He spoke as though of a real person he had met. ‘She would rather have died than have her husband disgrace himself.’

‘It turned out happily; through the theft she found her father again. He wasn’t even arrested.’

‘It makes no difference,’ said the serious youth; ‘he had luck, that is all. He shouldn’t have stolen. When she knows about it, it will break her heart.’

Ethics were his strong point, evidently. He had something to say again about the old man who, in the Franco-Prussian War, shot a soldier and allowed a young man to suffer the death penalty in his stead. It was true that the old man’s son had been shot and that there was no one else to care for the little grandson, and, while the critic admitted that that made a difference, he didn’t like the idea. The dramas appealed to him from a philosophical standpoint; one gathered that he and his companion might pass an evening discussing whether, when a man is a soldier, and therefore pledged to fight for his country, he has a right to give up his life to save that of an old man, even though he is the guardian of a child.

Throughout the whole show, throughout the discussion going on beside me, there was one face that I turned to again and again. It was that of an eager little girl of ten or eleven, whose lovely profile stood out in violent relief from the dingy wall. So rapt was she, so spellbound, that she couldn’t laugh, couldn’t clap her hands with the others. She was in a state of emotion beyond any outward manifestation of it.

In the Bowery you get a different kind of audience. None of your neighborhood spirit here. Even in what is called, the ‘dago show’ – that is, the show where the occasional vaudeville numbers are Italian singers — the people seem chance-met; the audience is almost entirely composed of men, only an occasional woman.

It was here that I met the moving-picture show expert, the connoisseur, for he told me that he went to a moving-picture show every night. It was the best way that he knew of spending your evenings in New York, and one gathered that he had early twenties, with a tough and honest countenance, and he spoke the dialect of the city of New York with greater richness than I have ever heard it spoken. He was ashamed of being caught by a compatriot in a ‘dago show.’

‘Say,’ he said, ‘dis is a bum joint. I don’t know how I come to toin in here. You don’t un’erstan’ what that skoit’s singin’, do you? You betcher I don’t!’

Not for worlds would he have understood a word of the inferior Italian tongue.

“I don’t never come to dago moving-picter shows,’ he hastened to assure me. ‘Say, if youse wanter see a real show, beat it down to Grand Street. Dat’s de real t’ing. Dese dago shows ain’t got no good films. You hardly ever see a travel film; w’en I goes to a show, I likes to see the woild. I’d like travelin’ if I could afford it, but I can’t; that’s why I like a good travel film. A good comic’s all right, but a good travel film or an a’rioplane race or a battle-ship review — dat’s de real t’ing ! You don’t get none here. I don’t know what made me come here,’ he repeated. He was sincerely displeased with himself at being caught with the goods by his compatriots in a place that had no class, and the only way he could defend himself was by showing his fine scorn of the inferior race.

You see what it means to them; it means Opportunity — a chance to glimpse the beautiful and strange things in the world that you haven’t in your life; the gratification of the higher side of your nature ; opportunity which, except for the big moving picture book, would be forever closed to you. You understand still more how much it means opportunity if you happen to live in a little country place where the whole town goes to every change of films and where the new films are gravely discussed. Down here it is that you find the people who agree with my friend of the Bowery — that ‘travel films is de real t’ing.’ For those people who would like to travel they make films of pilgrims going to Mecca; films of the great religious processions in the holy city of Jerusalem; of walrus fights in the far North. It has even gone so far that in Melilla there was an order for the troops to start out; they sprang to their places, trumpets blew, and the men fell into line and marched off — all for the moving-picture show. They were angry — the troops — but the people in Spain saw how their

armies acted.

In all the countries of the earth — in Sicily, and out in the desert of Arizona, and in the deep woods of America, and on the olive terraces of Italy — they are making more films, inventing new dramas with new and beautiful backgrounds, for the poor man’s theater. In his own little town, in some far-off fishing village, he can sit and see the coronation, and the burial of a king, or the great pageant of the Roman Church.

It is no wonder that it is a great business with a capitalization of millions of dollars, since it gives to the people whoneed it most laughter and drama and beauty and a chance for once to look at the strange places of the earth.

Comment: Mary Heaton Vorse (1874-1966) was a left-wing American journalist and novelist, deeply committed to issues of social justice. Bleecker Street is in Manhattan, within the Greenwich Village area.