Source: Henry Albert Phillips, ‘The New Motion Picture: No. 1 – The Teleview’, Motion Picture Magazine, August 1923, pp. 35-36, 86

Text:

The New Motion Picture

A Series of Searching Articles Showing the Constant Efforts of the Moving Picture to Re-Create Nature and Life as We Actually Experience It

I. THE TELEVIEW

By HENRY ALBERT PHILLIPS

Of the many thrills that enlivened my boyhood days, one stands out with vivid distinctness. As I recall it now, not a little of the original “kick” comes back with the recollection. I cannot help recalling with a certain amount of wistfullness the ravishing odor of candle grease and drying Christmas tree greens. For it was very early Christmas morning. And I had come down to see what Santa had brought me and stood there shivering from the cold and mingled emotions, when my eye fell on a pasteboard box about a foot long. It looked mysterious. I removed the red ribbon with trembling fingers and a rapidly beating heart. Within was excelsior — only wonderful things were wrapped in excelsior! I was further ecstatically tantalized to find the object inclosed in tissue paper. Each of these barriers heightened my imagination to a quite alarming state, and enhanced the value of the gift out of its true proportions.

The wonderful present proved to be a stereopticon. It consisted of a wooden canopy shaped to fit the brow and shade the eyes. You held it to your face and looked thru two windows of slightly magnifying glass at pictures which were set in a sliding cross-piece and regulated according to your astigmatism, or lack of it. The peculiar part of it was, that there were two pictures side by side on the picture card, one being identical with the [other]. I remember feeling that some mistake must have been made in the pictures they had sent me, likewise a sense of dreadful waste! If they had only put two different pictures on each card, I would have had twice as many! The pictures were photographs of noteworthy scenes the world over. There was the Brooklyn Bridge, I remember, with the low skyline of buildings in the background of New York of the eighties: there was a chamois standing on a mountain crag, with a breath-taking abyss beside him and other mountains in the background; and some hunters standing with their clogs in an open field, with a wood in the background. In other words, I remember, that there was always a foreground and a background in every picture, with distinct “air spaces” intervening between the two.

If for one moment, I had had any doubts of a possible commonplaceness in my stereopticon and its “views,” they immediately vanished when I looked thru the little windows and saw every object standing out both as big and as thick as life! I could actually see behind each object! By this, I mean objects did not appear as objects usually do when drawn on a flat surface, like so many facsimile shadows, but they actually had body, length, breadth and thickness and were actually separate from other objects around them. Why, you could actually feel the nearness of the near objects and calculate the distance of those far away. It was as tho each object in the picture had been cut out and stood up separately and accurately in relative distance one from the other.

This magical toy has never yet ceased to thrill and delight me. It brought ordinary scenes to life, or at least it lacked one essential which seemed too audacious for me to conjecture even — motion! Add motion to our three-dimension picture and the magic would be complete — for, bear in mind, that objects were magnified to the normal dimensions in which they would be perceived by the naked eye, known as “life-size.”

Well, this magic picture — which seemed too blasphemous for my boyish mind to consider possible — has come into being, like so many other undreamed-of wonders, in this Age of Invention in which we are living open-mouthed. The Moving Picture Stereopticon is here! They call it — possibly for the same reason that a living apartment in a more or less high building is called a “Flat” — the Teleview. That name has numbed thousands of potential patrons into a state of innocuous disinterestedness.

However, altho a name may give a thing a black eye, it cant hurt it if its character is good and sound. Call it even Teleview and the virtue of the device will survive.

It is human nature and cupidity in the crowd that makes it shrink from novelties of progress — especially if they have to dip their hands into their pockets and contribute a few cents to support the idea at a critical moment; while this same crowd, propelled by the same human nature, will flock en masse to witness some act of decadence — such as fire, murder or suicide — admission free! At the recent showing of the Teleview in one of New York’s big theaters, the public showed considerable interest over it — only when they had read the publicity stuff about it they yawned and went to bed, instead of going to see it and catering to their better faculties. Several of the passholders in the seat behind me showed that rare good taste so often exhibited by pass-holders — and all other people who get good things for nothing – by sneering audibly during the performance and, on leaving, announcing in scornful tones that the whole show was rotten.

There is probably something to be said on both sides. Restricting ourselves to the Teleview process of projection, I must acknowledge having witnessed a really marvelous exhibition. When we step aside from the invention proper and touch upon the judgment and skill of those responsible for the selection and production of “the first moving picture to be produced in three dimensions,” then I too must join those who remarked that there was surely something rotten in Teleview’s Denmark.

The picture-play was called “M-A-R-S.” From scenario to directing, and directing to acting, it was among the worst ten pictures I ever saw, and that is saying a great deal. To mention names in this instance is to call names. They have suffered enough. But the point remains, that Teleview suffered a great deal unjustifiedly. The critics went and their odoriferous opinion of the picture made them dub the whole performance as being one and the same piece of cheese. Honest, interested spectators came and had their sincere enthusiasm numbed by an hour and a half’s boredom. Outside, were thousands upon thousands of credulous people who would have been willing to go to see Teleview — and kill two movie birds with one stone as it were, by seeing this wonderful new process and a good picture at the same time — if the picture had been only as bad as the average. So their scientific end was excellent, but their artistic end was not. Because of this error — oh, so common! — in artistic judgment and execution, thousands of people may not see this wonderful new process so soon as they might otherwise have done so.

The reason for all this is simple. Teleview picture making is costly from beginning to end. A special camera is necessary, a special method in the processes between exposure and projection, and, finally, in seeing the pictures on the screen it is necessary for each individual spectator to look thru what corresponds to our former stereopticon, which consists of two little windows within which passes a revolving shutter operated by a tiny motor. Here’s the rub — both in the matter of enormous expense to the producer, and also in [that] of training the spectator to his comfort and savoir faire [to] adjust his individual apparatus and maintain the rigid poise necessary to keep his eyes on a level with the small apertures.

The Teleview method of motion picture photography, production and projection is the invention of Lawrence Hammond, assisted by William F. Cassidy, both of the class of 1919 at Cornell.

Looking with the naked eye upon Teleview pictures projected on the screen, we find a blurred double image with a fuzzy suggestion of chromatic colors permeating it. And it is true that there really are two images on the screen; one superimposed — slightly off-center — over the other. In the projection-room you will find two projection machines operating in co-ordination and each throwing its contributive image on the screen simultaneously. Going further back, we learn that the subject-matter was originally photographed with a stereoscopic, or double-lensed, camera these lenses have been adjusted to a distance apart corresponding to the space — optically speaking — between the two human eyes.

An observation by the writer at this point might be helpful to the reader in understanding and visualizing the Teleview method at this stage of its development. Several years ago I had a serious infection of the eyes. An operation and heroic treatment effected a cure, but I suffered a collapse of the optical muscles. They refused to binoculate. I saw two images. Each eye saw separately. You can do the same thing, by deliberately forcing the eyeballs to draw themselves so as to look in two straight parallel lines. You will then see two slightly blurred images.

The ingenious feature of the method is introduced at this point. Just before the projection on the screen begins, spectators become aware that the stereoscope device, thru which they must look at the screen, has suddenly come to life! We can hear a slight whirring and feel a tiny smooth vibration within. It is the motor within each instrument. Perhaps we had noted on first examining the instrument that it contained a small, two-vaned “shutter,” which persisted in sticking in one of the windows and thus threatening to spoil our clear view of the screen. But now we note with satisfaction that the shutter has mysteriously disappeared! The fact is that it is revolving so fast that we cannot see it.

Now, this shutter co-ordinates perfectly with the projection machine and cuts off the vision of each eye alternately so that one eye sees one “frame” — as each separate picture that forms the strip of pictures is called — and the other eye sees only the following or alternate one. Because of the infinitesimal elapse of time — l/196th of a second — of the duration of each impression, they seem to be simultaneous but separate images. When they are blended in the brain they give the sensation of depth, observable in the old- fashioned stereoscope. The ordinary rate of 16 pictures to the foot is used.

The cost of equipping a theater with mechanical shutters is given by the inventors as five dollars a seat, separate shutters being necessary for each observer. The cost of producing a picture by this method is said to be about double.

The result of witnessing a Teleview moving picture is startling. In stereoscope “still” pictures we were impressed with the realism induced by the appearance of solid images with perceptible air-spaces between them. With these “real” images set in motion, the effect is astonishing. But one gets a real thrill when moving objects are set in motion coming directly toward the spectator. They actually leap from the screen! The result is uncanny. One shrinks back for an instant to avoid what must prove a disastrous impact. The illusion is perfect.

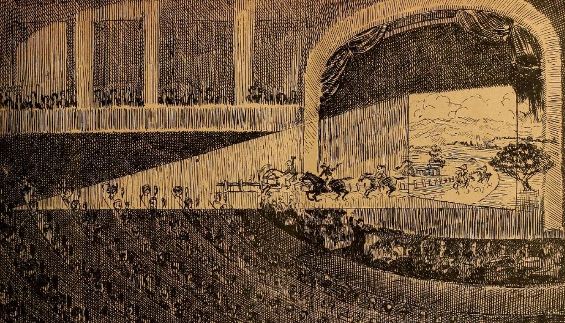

The background of the photographic picture appears to be no farther distant than the surface of the actual screen from the spectator. Any person or object in the picture that moves in any degree from the picture background toward the observer seems actually to step out of the picture and approach. Thus moving figures appear to be carrying on the action on a real stage projected toward the audience in front of a realistic back-drop.

What presumably happens is that objects approach just as close to each individual spectator as they did to the camera. The audience is really looking thru the lens of the camera, which has been made to synchronize with the universal focus and vision of all who see it thereafter. The eye of the cameraman has attended to that. Thus, if an object is moved to within six feet of the camera, it seems to have emerged from the background and approached to within the same distance of each spectator. I sat at a distance of let us say one hundred feet from the screen and yet the illusion in one or two instances was so perfect that I felt convinced that if I had put out my hand I could almost have touched the foremost objects in the picture!

And Teleview is only one of the many indications showing the marvelously rapid advance of the motion picture to spheres of perfection and efficiency at which we can only hazard a guess from day to day!

Comments: Henry Albert Phillips (1880–1951) was an American film scenarist and editor of Motion Picture Magazine. The science-fiction feature film M.A.R.S. (aka The Man from M.A.R.S.) was first exhibited in December 1922 as part of a programme of films demonstrating the ‘teleview’ invention of Laurens Hammond (also inventor of the Hammond organ). The ‘teleview’ was a glass viewer with a revolving shutter attached to the side of the cinema seat that was operated by a small motor. The special ‘teleview’ camera had two lenses, giving a blurred picture to the naked etye, but through the projection device a stereoscopic effect was produced, though the effect was restricted to a small projection space. The film was re-issued in August 1923 as Radio-Mania in non-stereoscopic form, being either entirely re-shot or possibly filmed simultaneously with a normal camera. No further ‘teleview’ films were made. Stereopticon was an American term for the magic lantern.

Links: Copy at Internet Archive