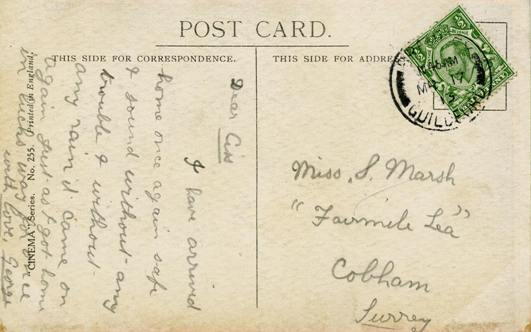

Source: The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1922), pp. 318-320

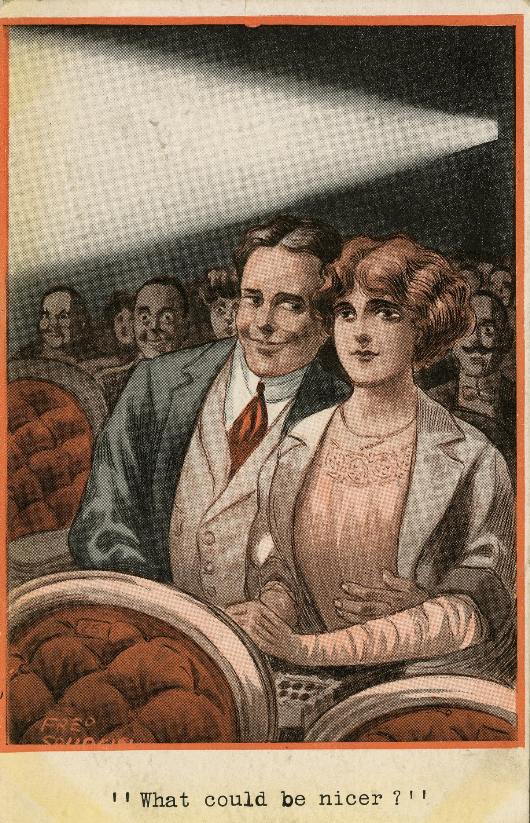

Text: Reports of investigators indicate that the managers of movies are convinced that their main floors, at least, should be guarded against Negroes. In most of the commercial amusement places, Negroes seldom have difficulty if they are willing to sit in the balcony, though attempts are frequently made to seat them on the aisles next to the walls, even when there are center seats empty. It is rare that any report is obtained of objections by white patrons to the actual presence of Negroes when they are well-mannered, well-dressed, and appreciative auditors.

As a rule movie theaters do not sell reserved seats, general admission entitling any patron to any seat in the house. But the following detailed report of the experience of two intelligent, well-dressed, quiet-mannered Negro women at a new movie theater on State Street is typical:

Purchased tickets, and entered the large lobby which extends across the front of the house. From this lobby there are closed doors at the entrance of several aisles, so that patrons are directed by ushers to different aisles, supposedly wherever there are vacant seats. We followed directions, and went to the extreme left of the lobby.

We opened the door, and the usher in charge of this aisle started down toward the front to show us seats. We saw at once that the narrow section of seats next to the wall was empty except for one colored woman sitting about the middle of the section. Instead of following the usher down the aisle, and taking seats indicated to the right of this section, we turned through a row of empty seats on the left-hand section, and sat next to a woman in the aisle seat. This put us two rows from the rear in a side middle section, instead of in the section which seemed to be reserved for colored patrons, next to the wall. As the usher returned to his station he said, “We have some lovely seats in the balcony; wouldn’t you prefer sitting there?” He was courteous, and I thanked him, telling him that we were quite satisfied with the seats we had taken.

Later, seeing two vacant seats further front in the center section which gave us a much better view we decided to take them and see what would happen. As we rose, the usher tried to block ms by putting his hands on the back of the seat in front, and saying, “I am sorry that you can’t take those seats.” I brushed by him and took one of the seats. He tried the same thing with Mrs. H — , and she also brushed by and joined me. There were scattered vacant seats both in the section we left and the one to which we moved. We remained until the end of the show without embarrassment.

The manager of this theater has had many years of experience in Chicago, and was quite willing to discuss race contacts. Nothing in his words would indicate any strong prejudice against Negroes, even when expressing his conviction that they should keep to places intended especially for them. He said, in substance:

Not many Negroes buy tickets — perhaps ten or a dozen a day. An effort is made to seat them in one section of the house, preferably the balcony, to which they are directed by ushers. Reason is the complaint by white patrons who object to sitting next to them for an hour, or hour and a half. Offensive odor reason usually given. White patrons often complain to manager as they go out if Negro has been sitting near them.

Conduct of Negroes is not often objectionable — runs about the same as all patrons. Occasionally one tries to “start something.” Recently two Negroes came to manager in crowded lobby after they had attended the show and objected to their seats on the balcony to which they had been sent by ushers, saying there were vacant seats on the main floor. Wanted to know why they were discriminated against. Manager did not want an argument in the presence of other patrons, and told them that as they had seen the show, heard the music, and shared everything with other patrons, he did not see they had any real cause for complaint. Called attention to the notice printed on almost every theater ticket in some form or other to the effect that the management reserves the right to revoke the license granted in the sale of the ticket, by refunding the money paid.

The same two women bought tickets the next day and attended a movie in an older and very popular “Loop” theater. They reported that they had no difficulty of any kind.

In a test made of a new and popular movie theater in an outlying section the investigator reported:

There were four of us in the party on June 5. We were told by the usher that there were no seats on the first floor, and that we would find seats in the first balcony. I think he was right, for there were white people also sent to the balcony. We were ushered in promptly, but another usher met us and said, “Right on up to the second balcony.” We said we preferred seats in the first balcony, and walked by him. He went and got two more ushers and stood in front of us to prevent us from going into the first balcony, insisting that there were no seats there. One of the young ladies stepped around the usher, and saw three vacant seats. She called them to the attention of the usher, and he then said he meant there were no seats for four. Two of our party took those seats, and the other two waited about twenty minutes till they could get the seats they wanted. After getting into the first balcony, we saw vacant seats in at least four rows, two, three, and four seats together into which we might quietly have gone had the usher been courteous.

On June 18, 1920, a well-known Negro employed in the City Hall was denied admission to a movie theater at Halsted and Sixty-third streets. There is a small but long-established Negro colony about a mile west of this location.

Comments: The Negro in Chicago is a report commissioned by the Chicago Commission of Race Relations following severe racial disturbances in the city in 1919. In Northern states Black audiences had the legal right to be seated anywhere at a public entertainment, but many cinemas and theatres attempted to keep them to segregated areas (often the balcony), or might charge them higher prices than white audiences. Some cinemas had separate entrances for blacks. Southern states enforced racial segregation under the Jim Crow laws. Cinemas managed solely for black audiences existed in both North and South.

Links: Copy at Internet Archive