Source: Dorothy Richardson, ‘Continuous Performance V: There’s No Place Like Home’, Close Up vol. I no. 5, November 1927, pp. 44-47

Text: Short of undertaking pilgrimages we remain in ignorance of new films until they become cheap classics. Not completely in ignorance for there is always hearsay. But these films coming soon or late find us ready to give our best here where we have served our apprenticeship and the screen has made in us its deepest furrows. It is true that an excellence shining enough will bring out anywhere and everywhere our own excellence to meet it. And the reflected glory of a reputation will sometime carry us forth into the desert to see. But until we are full citizens of the spirit, free from the tyranny of circumstance and always and everywhere perfectly at home, we shall find our own place our best testing-ground and since, moreover, we are for THE FILM as well as for FILMS, we prefer in general to take our chance in our quarter, fulfilling thus the good bishop’s advice to everyman to select his church, whether in the parish or elsewhere near at hand, and remain there rather than go a-whoring after novelties. The truly good bishop arranges of course that the best, selected novelties shall circulate from time to time.

Meanwhile in the little bethel there is the plain miraculous food, sometimes coarse, sometimes badly served, but still miraculous food served to feed our souls in this preparatory school for the finer things that soon no doubt will be raising the level all round. And we may draw, if further consolation be needed, much consolation from the knowledge that, in matters of feeding, the feeder and the how and the where are as important as the what.

Once through the velvet curtain we are at home and on any but first nights can glide into our sittings without the help of the torch. There is a multitude of good sittings for the hall is shaped like a garage and though there are nave and two aisles with seats three deep, there are no side views. Something is to be said for seats at the heart of the congregation, but there is another something in favour of a side row. It can be reached, and left, without squeezing and apologetic crouching. The third seat serves as a hold-all. In front of us will be either the stalwart and the leaning lady, forgiven for her obstructive attitude because she, also an off-nighter, respects, if arriving first, our chosen sittings, or there will be a solitary, motionless middle-aged man. There is, in proportion to the size of the congregation, a notable number of solitary middle-aged male statues set sideways, arm over seat, half -persuaded, or wishing to be considered half-persuaded. Behind there is no one, no commentary, no causerie, no crackling bonbonnieres. The torch is immediately at hand for greetings and tickets and, having disposed ourselves and made our prayers we may look forth to find the successor of Felix making game of space and time. Hot Air beating Cold Steel by a neck, or, if we are late, an Arrow collar young man, collarless, writhing within ropes upon the floor of the crypt whose reappearance will be the signal for our departure. Perfection, of part or of whole, we shall rarely see, but there is no limit to vision and if we return quite empty-handed we shall know whose is the fault. The miracle works, some part of it works and gets home. And sometimes one of the “best” to date is ours without warning.

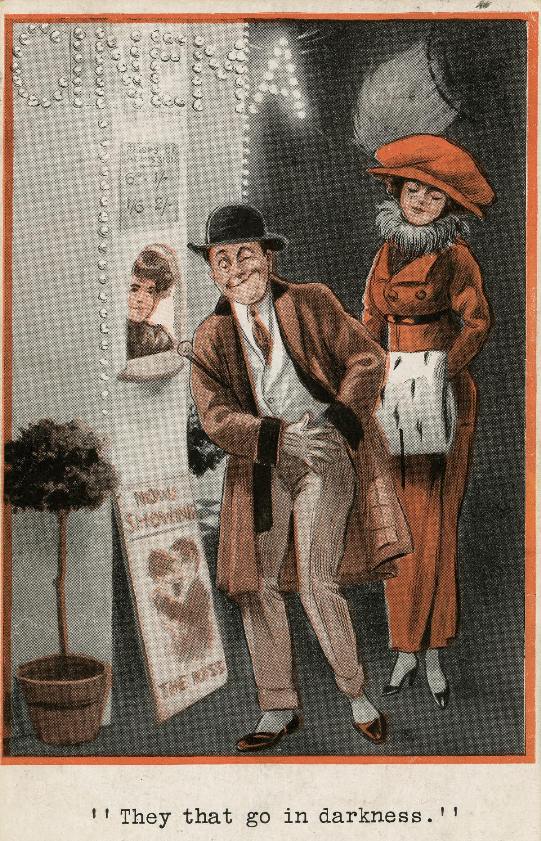

For any sake let everyman have his local cinema to cherish or neglect at will, and let it be, within reason, small. Small enough to be apprehended at a glance. And plain. That is to say simple. The theatre may be as ornate, as theatrical as it likes, the note of the cinema is simplicity. Abandon frills all ye who enter here. And indeed while dramatic and operatic enterprise is apt, especially in England, to be in part social function the cinema, though subtly social, is robbed by necessity of the chance of becoming a parade ground. One cannot show off one’s diamonds in the dark. Going to the cinema is a relatively humble, simple business. Moreover in any but the theatre’s more vital spaces it is impossible to appear in an old ulster save in the way of a splendiferous flouting of splendour that is more showy than diamonds. To the cinema one may go not only in the old ulster but decorated by the scars of any and every sort of conflict. To the local cinema one may go direct, just as one is.

For the local, or any, cinema the garage shape is the right shape because in it the faithful are side by side confronting the screen and not as in some super-cinemas in a semi-circle whose sides confront each other and get the screen sideways. The screen should dominate. That is the prime necessity. It should fill the vista save for the doorways on either side whose reassuring “Emergency Exit” beams an intermittent moonlight. It is no doubt because screens must vary in size according to the distance from them of the projector that the auditorium of the super-cinema (truly an auditorium for there is already much to be heard there) is built either in a semi-circle or in an oblong so wide that the screen, though proportionately larger, looks much smaller than that of a small cinema, seems a tiny distant sheet upon which one must focus from a surrounding disadvantageously-distributed populous bigness. The screen should dominate, and its dominating screen is one of the many points scored by the small local cinema.

For the small local cinema that will remain reasonably in tune with the common feelings of common humanity both in its films and in its music, there is a welcome waiting in every parish.

Comments: Dorothy Richardson (1873-1957) was a British modernist novelist. Through 1927-1933 she wrote a column, ‘Continuous Performance’ for the film art journal Close Up. The column concentrates on film audiences rather than the films themselves. ‘Felix’ is a reference to the cartoon character Felix the Cat. The Arrow Collar Man was a familiar figure from advertisements for shirts and detachable shirt collars.

Links: Copy at Internet Archive