Source: Dorothy Richardson, ‘Continuous Performance: Pictures and Films’, Close Up vol. IV no. 1, January 1929, pp. 51-57

Text:

American films, sharp as steel, cold like the poles, beautiful as the tomb, passed before our dazzled eyes. The gaze of William Hart pierced our hearts and we loved the calm landscape where the hoofs of his horse raised clouds of dust.

Quite so. True, true, perfectly true. Something, at any rate, did, pierce our hearts, and we did love the calm of the landscape whereon the wild riders flew, the dust-clouds testifying to their pace. Just those things and as they were, unrelated to what came before and after. And to whatever it might be that had preceded, and to whatever it was that might follow, the splendid riding in the vast landscape gave its peculiar quality. We were devotees of the vast landscape and the wild riding and all the rest passing so magnificently before our eyes.

But however devout our feelings it did not occur to us to express them quite so openly and prayerfully. And, I beg … has not the quoted tribute a strange air? An air at first sight of being an extract from an out-of-date hand-book on the year’s pictures, part of whose compilation had been entrusted to a youth with literary ambitions, and a somewhat exotic youth at that, and therefore a youth who properly should not have been the prey of the wild west film? And yet here most certainly is cri du coeur, with no question of tongue in cheek.

But young Englishmen of no period, and under no matter what provocation, are to be found gushing in these terms. Gush they may. But not quite in these terms. A young Englishwoman, then? An aspiring and enthusiastic young Englishwoman writing to suggest to other aspiring and enthusiastic young Englishwomen exactly what they think about the movies, and well understanding the heart-piercing and the adoration of the landscape.

But though the sentiments may be thus accountable, the expression of them remains a little mysteriously not an English form of expression until – turning the page to discover in whose person it was that The Little Review at any point in its thrilled and thrilling career should have waxed lyrical over the movies in their own right, as distinct from their glimpsed possibilities – one finds the signature of a French writer, one of the super-realists who had hoped the war would have rescued art from romanticism, had been disappointed and, having enumerated the few artists who in Europe were giving the world anything worth the having, looked sadly back upon the movies in their pristine innocence.

With the strange unsuitability of the English garb to the sentiments expressed thus cleared up by the realisation that the article was a literal translation, one could give rein to one’s delight in the discovery of this genuine feeling of the day before yesterday, even though immediately one was forced to reflect that this wistful young man, given the circumstances and the date, could not possibly have seen any FILMS.

Accepting, therefore, its French reading, I have set down this tribute in the manner of a text, first because with an odd punctuality it came to my notice immediately on my return, from a first visit to London’s temple of good films, to get on with the business of extracting forgotten treasures from a packing-case, and also because its sentiments chimed perfectly with certain convictions floating uninvited into my mind as I talked, on matters unrelated to the film (if, indeed, at this date any matters can be so described), with a friend encountered by chance on my way home from The Avenue Pavilion.

I had seen, in great comfort, and from a back seat whose price was that of the less valuable portions of the average super-cinema, The Student of Prague. This film, I am told, though excellent for the date of its production, a good play, well acted and likely to remain indefinitely upon any well-chosen repertory, has been out-done and left behind by films now being shown in Germany and in Russia. It is approved by the film intelligentsia, including psycho-analysts who delightedly find it, like all works of art, ancient and modern, fuller of wisdom than its creator clearly knows. And it was most heartily approved by a large gathering of onlookers, revealed when the lights went up, as consisting for the most part of those kinds of persons to be seen scattered sparsely amongst the average cinema crowd.

For me, personally, and before the human interest of the drama began to compete with whatever conscious critical faculty I may possess, it joined forces with the few ‘good’ films I have seen at home and abroad in convincing me that the film can be an ‘art-form’. There is much in it I shall never forget, and that much was supported and amplified in a way that no conceivable stage setting can compete with. The absence of the spoken word was more than compensated. Captions there may have been. I remember none. Clear, too, was the role of the musical accompaniment, though this was now and again a little obtrusive, and one grew intolerant of the crescendo of cymbal-crashing that accompanied every great moment instead of being reserved for the post-script, the final discomfiture of the wonderful devil with the umbrella, surely one of the best devils ever seen on stage or film? The same uniform cymbal-crashing did much, a week or so later, to spoil the revival of Barrymore’s Jekyll and Hyde, first seen in England to the tune of the Erl-könig, itself a work of art and fitting most admirably to Barrymore’s achievement.

But the rôle of the musical accompaniment was clear, nevertheless, its contribution to the business of compensating the absence of the spoken word, its support and its amplification that joins the many other resources of the film in deepening and unifying and driving home all that is presented. Conrad Veidt on any stage would be a great actor. Conrad Veidt moving voiceless through the universal human tragedy in surroundings whose every smallest item ‘speaks to the occasion’ has the opportunity that at last gives to pure acting its fullest scope.

I left gratefully anticipating such other good films as it may:be my fortune to see. Yet within and around my delights there were, I knew, certain reservations at work waiting to formulate themselves and, as I have said, taking the opportunity, the moment my attention was busy elsewhere, of coming forward in the form of clear statement.

The burden of their message was that welcome for the FILM does not by any means imply repudiation of the movies. The FILM at its utmost possible development can no more invalidate the movies than the first-class portrait, say Leonardo’s of the Lady Lisa, can invalidate a snap-shot.

The film as a work of art is subject to the condition ruling all great art: that it shall be a collaboration between the conscious and the unconscious, between talent and genius. Let either of these elements get ahead of the other and disaster is the result, disaster in proportion to the size of the attempt.

The film, therefore, runs enormous risks. Portraits are innumerable. The great portraits produced by any single nation are very few indeed. And the portrait that is merely clever or pretentious, be its technique what it will, is no food for mankind. But the snap-shot, and the movie that offers to the fool and the wayfaring man a perfected technique, is food for all. It can’t go wrong. It is innocent, and its results go straight to the imagination of the onlooker, the collaborator, the other half of the game.

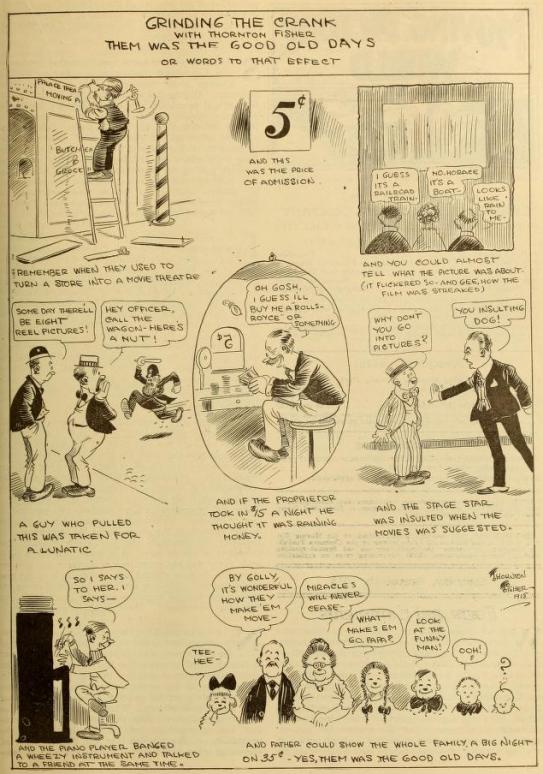

The charm of the first movies was in their innocence. They were not concerned, or at any rate not very deeply concerned, either with idea or with characterisation. Like the snap-shot, they recorded. And when plot, intensive, came to be combined with characterisation, with just so much characterisation as might by good chance be supplied by minor characters supporting the tailor’s and modiste’s dummies filling the chief rôles, still the records were there, the snap-shot records that are always and everywhere food for a discriminating and an undiscriminating humanity alike. ‘Sharp as steel, cold like the poles’; of landscape calm or wild, of crowds and all the moving panorama of life, of interiors, and interiors opening out of interiors, an unlimited material upon which die imagination of the onlooker could get to work unhampered by the pressure of a controlling mind that is not his own mind.

I was reminded also that the Drama, for instance, the Elizabethan drama, became Great Art only in retrospect. Worship of Art and The Artist is a modern product. In the hey-day of the Elizabethan drama the stage was despised, the actor a vagabond and a low fellow.

It may be that the hey-day of the film will come when things have a little settled down. When the gold-diggers, put out of court, shall have ceased to dig, when the medium is developed and within reach of the vagabonds and low fellows, when writing for the film shall no longer offer a spacious livelihood. Then, by those coming innocently to a well-known medium, the World’s Great Films, the Hundred Best Films, will be produced. And, since history never repeats itself, they will probably be thousands, some of which, it would seem, have already been made in pioneering Russia.

But the movies will remain. The snap-shots will go on all the time. And there will always be people who infinitely prefer the family album of snap-shots to the family portrait gallery. And this is not necessarily the same as saying that there will always be irresponsible people, people who are happy merely because they are infantile. Much has been said, by those who dislike the pictures, of their value as evidence of infantilism. It is claimed that the people who flock to the movies do so because they love to lose themselves in the excitements of a dream-world, a world that bears no relationship to life as they know it, that makes no demand upon the intelligence, acts like a drug, and is altogether demoralising and devitalising.

Such people obviously know very little about the movies. But even if they did, even if they cared to take their chance and now and again submit themselves to the experience of a thoroughly popular show, it is hardly likely that they would lose their apparent inability to distinguish between childishness, the quality that has of late been so admirably analysed and presented under the label of infantilism, and childlikeness, which is quite another thing. The child trusts its world, and those who, in all civilisations and within all circumstances, in face of all evidence and no matter what experience, cannot rid themselves of a child-like trust are by no means to be confused with those who shirk problems and responsibilities and remain ego-centrically within a dream-world that bears no relation to reality.

The battles and the problems of those who trust life are not the same as the battles and problems of those who regard life as the raw material for great conflicts and great works of art. But only such as regard the Fine Arts as mankind’s sole spiritual achievement will reckon those who appear not to be particularly desirous of these achievements as therefore necessarily damned.

Comments: Dorothy Richardson (1873-1957) was a British modernist novelist. Through 1927-1933 she wrote a column, ‘Continuous Performance’ for the film art journal Close Up. The column concentrates on film audiences rather than the films themselves. The films mentioned are Der Student von Prag (Germany 1926) and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (USA 1920). The Avenue Pavilion cinema was in Shaftesbury Avenue, London, and specialised in showing foreign films. The Little Review was an American literary magazine.

Links: Copy at Internet Archive