Source: Extracts from Karl Brown, Adventures with D.W. Griffith (London: Secker & Warburg, 1973), pp. 86-95

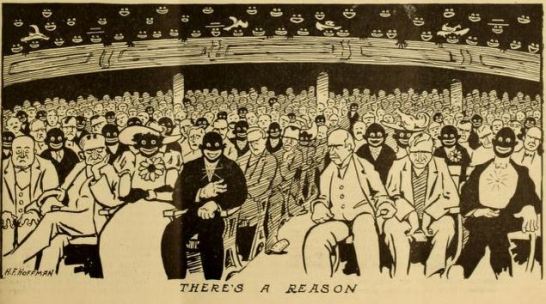

Text: It was a packed house, with swarms of people standing around outside, hoping for cancellations so they could get in anywhere at all, even in the top gallery. I never saw or felt such eager anticipation in any crowd as there was at that opening night. We three, my father, my mother, and I, had been given choice seats saved for us by Frank Woods. My parents, old-stagers at the business of opening nights, were all keyed up to a state of high tension, while I – well, I was feeling a little sick because I knew what the picture really was, just another Biograph, our four times as long. I simply couldn’t help feeling that it had been a tragic mistake to build up such a fever pitch of eager anticipation, only to let them down by showing them what was bound to be just another movie. Only longer, much longer, three hours longer. What audience, however friendly, could possibly sit through that much of nothing but one long, one very long movie of the kind they had seen a hundred times before?

My first inkling that this was not to be just another movie came when I heard, over the babble of the crowd, the familiar sound of a great orchestra tuning up. First the oboe sounding A, then the others joining to produce an ever-changing medley of unrelated sounds, with each instrument testing its own strength and capability through this warming-up preliminary. Then the orchestra came creeping in through that little doorway under the proscenium apron and I tried to count them. Impossible. Too many. But there were at least seventy, for that’s where I lost count, so most if not all of the Los Angeles Symphony orchestra had been hired to “play” the picture.

[…]

The house lights dimmed. The audience became tensely silent. I felt once again, as always before, that strange all-over chill that comes with the magic moment of hushed anticipation when the curtain is about to rise.

The title came on, apparently by mistake, because the curtain had not yet risen and all I could see was the faint flicker of the lettering against the dark fabric of the main curtain. But it was not a mistake at all, because the big curtain rose slowly to disclose the title, full and clear upon the picture screen, while at the same time [Joseph Carl] Briel’s baton rose, held for an instant, and then swept down, releasing the full impact of the orchestra in a mighty fanfare that was all but out-roared by the massive blast of the organ in an overwhelming burst of earth-shaking sound that shocked the audience first into a stunned silence and then roused them to a pitch of enthusiasm such as I had never seen or heard before.

Then, of course, came those damned explanatory titles that I had shot time and time again as Griffith and Woods kept changing and rechanging them, all with the object of having them make as much sense as possible in the fewest possible words. Somehow, the audience didn’t seem to mind. Perhaps they were hardened to it. They should have been, by now, because whenever anybody made any kind of historical picture, it always had to be preceded by a lot of titles telling all about it, not to mention a long and flowery dedication thanking everyone from the Holy Trinity to the night watchman for their invaluable cooperation, without which this picture would not have been possible.

The orchestra sort of murmured to itself during the titles, as though to reassure the audience that they couldn’t last forever. And then … the picture, gliding along through its opening sequences on a flow of music that seemed to speak for the screen and to interpret every mood. The audience was held entranced, but I was not. I was worried in the same way that young fathers, waiting to learn whether it’s a boy or a girl, are worried. I was worried, badly worried, about the battle scenes, and I wished they’d get through fiddle-faddling with that dance and all that mushy stuff and get down to cases. For it was a simple, open-and-shut matter of make or break as far as I could see; and I could not see how that mixed-up jumble of unrelated bits and pieces of action could ever be made into anything but a mixed-up jumble of bits and pieces.

Well, I was wrong. What unfolded on that screen was magic itself. I knew there were cuts from this to that, but try as I would, I could not see them. A shot of the extreme far end of the Confederate line flowed into another but nearer shot of the same line, to be followed by another and another, until I could have sworn that the camera had been carried back by some sort of impossible carrier that made it seem to be all one unbroken scene. Perhaps the smoke helped blind out the jumps, I don’t know. All I knew was that between the ebb and flow of a broad canvas of a great battle, now far and now near, and the roaring of that gorgeous orchestra banging and blaring battle songs to stir the coldest blood, I was hot and cold and feeling waves of tingling electric shocks racing all over me.

[…]

Somewhere during my self-castigation a title came on reading INTERMISSION. So soon? I asked my father the time. He pulled out his watch, snapped open the case, and said it was nine thirty. Preposterous. Somehow during the past fifteen minutes, or not more than twenty, an hour and a half had sneaked away.

We went out with the rest of the crowd to stretch our legs and, in true backstage fashion, to eavesdrop on the comments of the others. There was enthusiasm, yes; lots of it. It had been exactly as grandpa had described it was the consensus, only more real. There were also a few professionals who were wisely sure that Griffith was riding for all fall. “You can;t shoot all your marbles in the first half and have anything left for your finish” was the loudly expressed opinion of a very portly, richly dressed gentleman. “That battle was a lulu, best I’ve seen, and that assassination bit was a knockout, I ain’t kidding you. But what’s he going to do for a topper, that’s what I want to know. I’ll tell you what’s going to happen. This thing is going to fizzle out like a wet firecracker, that’s what it’s going to do. Don’t tell me, I know! I’ve seen it happen too many times. They shoot the works right off the bat and they got nothing left for their finish. You wait and see. You just wait and see.”

[…]

And yet it wasn’t the finish that worried me so much as the long, dull, do-nothing stuff that I knew was slated for the bulk of the second half. Stuff like the hospital scenes, where Lillian Gish comes to visit Henry Walthall, she in demurest of dove grey, he in bed with a bandage neatly and evenly wrapped around his head. Now what in the world can anyone possibly do to make a hospital visit seem other than routine? He’ll be grateful, and she’ll be sweetly sympathetic, but what else? How can you or Griffith or the Man in the Moon possibly get anything out of such a scene? Answer: you can’t. But he did, by reaching outside the cur-and-dried formula and coming up with something so unexpected, and yet so utterly natural, that it lifted the entire thing right out of the rut and made it ring absolutely true.

Since this was an army hospital there had to be a sentry on guard. So Griffith looked around, saw a sloppy, futile sort of character loitering about, and ran him in to play the sentry, a fellow named Freeman, not an actor, just another extra. Well, Lillian passed before him and he looked after her and sighed. In the theater and on the screen, that sigh became a monumental, standout scene, because it was so deep, so heartfelt, and so loaded with longing for the unattainable that it simply delighted the audience. But not without help. Breil may not have been the greatest composer the world has ever known but he did know how to make an orchestra talk, and that sigh, uttered by the cellos and the muted trombones softly sliding down in a discordant glissando, drove the audience into gales of laughter.

[…]

I endured the “drama” – all that stuff with Ralph Lewis being shown up as a fake when he wouldn’t let his daughter marry George Siegmann because he was a mulatto – all because I was itching to get to the part where Walter Long chased Mae Marsh all over Big Bear Valley, running low and dripping with peroxide. What came on the screen wasn’t Walter Long at all. It was some sort of inhuman monster, an ungainly, misshapen creature out of a nightmare, not running as a human being would run but shambling like a gorilla. And Mae Marsh was not fluttering, either. She was a poor little lost girl frightened out of her wits, not knowing which way to turn, but searching, searching for safety, and too bewildered to know what she was doing. So she ran to the peak of that rock, and when the monster came lumbering straight at her, she … well, all I can say is that it was right, absolutely, perfectly, incontestably right.

And did the audience hate Griffith for letting them down? Not a bit of it. When the clansmen began to rise,the cheers began to rise from all over that packed house. This was not a ride to save Little Sister but to avenge her death, and every soul in that audience was in the saddle with the clansmen and pounding hell-for-leather on an errand of stern justice, lighted on their way by the holy flames of a burning cross.

[…]

So everyone was rescued and everyone was happy and everyone was noble in victory and the audience didn’t just sit there and applaud, but they stood up and cheered and yelled and stamped feet until Griffith finally made an appearance.

If you could call it an appearance. Now I, personally, in such a situation would have bounded out to the center of the stage with both hands aloft in a gesture of triumph, and I would probably have shaken my hands over my head, as Tom Wilson had told me was the proper thing for any world’s champion to do at the end of a hard-fought but victorious fight.

Griffith did nothing of the sort. He stepped out a few feet from stage left, a small, almost frail figure lost in the enormousness of that great proscenium arch. He did not bow or raise his hands or do anything but just stand there and let wave after wave of cheers and applause wash over him like great waves breaking over a rock.

Then he left. The show was over. There was an exit march from the orchestra, but nobody could hear it. People were far too busy telling one another how wonderful, how great, how tremendous it had all been.

Comments: Karl Brown (1896-1990) was an American cinematographer and director. He served as assistant to cinematographer Billy Bitzer on D.W. Griffith’s feature film The Birth of a Nation. His memoir Adventures with D.W. Griffith is one of the best first-hand accounts of silent era film. The event recalled here is the premiere at Clune’s Auditorium, Los Angeles, on 8 February 1915, when the film was still known as The Clansman. The composer Joseph Carol Breil did not conduct at the premiere – it was Carli Elinor, conducting his own score. Brown’s memory sometimes places film sequences in the wrong order, though Griffith did re-edit the film after initial screenings and in response to requests by censorship boards. Frank Woods was co-scriptwriter on the with with Griffith. Walter Long was a white actor playing a black character, Gus.