Source: Barton W. Currie, ‘The Nickel Madness,’ Harper’s Weekly, 24 August 24 1907, pp. 1246-1247.

Text: The Nickel Madness

The Amazing Spread of a New Kind of Amusement Enterprise Which is Making Fortunes for its Projectors

The very fact that we derive pleasure from certain amusements, wrote Lecky, creates a kind of humiliation. Anthony Comstock and Police-Commissioner Bingham have spoken eloquently on the moral aspect of the five-cent theatre, drawing far more strenuous conclusions than that of the great historian. But both the general and the purity commissioner generalized too freely from particulars. They saw only the harsher aspects of the nickel madness, whereas it has many innocent and harmless phases.

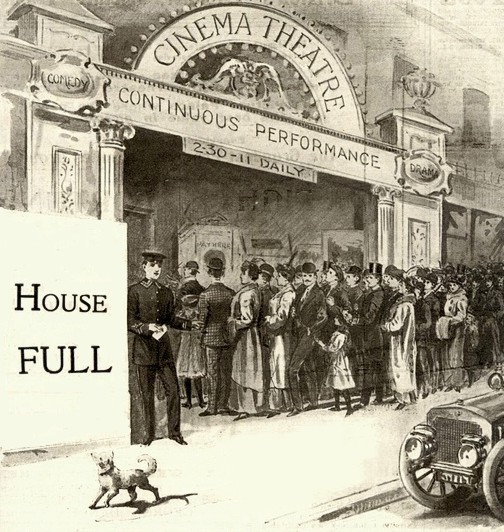

Crusades have been organized against these low-priced moving-picture theatres, and many conservators of the public morals have denounced them as vicious and demoralizing. Yet have they flourished amazingly, and carpenters are busy hammering them up in every big and little community in the country.

The first “nickelodeon,” or “nickelet,” or whatever it was called was merely an experiment, and the first experiment was made a little more than a year ago. There was nothing singularly novel in the ideal, only the individualizing of the moving-picture machine. Before it had served merely as a “turn” in vaudeville. For a very modest sum the outfit could be housed in a narrow store or in a shack in the rear yard of a tenement, provided there was an available hallway and the space for a “front.” These shacks and shops are packed with as many chairs as they will hold and the populace welcomed, or rather hailed, by a huge megaphone-horn and lurid placards. The price of admission and entertainment for from fifteen to twenty minutes is a coin of the smallest denomination in circulation west of the Rockies.

In some vaudeville houses you may watch a diversity of performances four hours for so humble a price as ten cents, provided you are willing to sit among the rafters. Yet the roof bleachers were never so popular or profitable as the tiny show-places that have fostered the nickel madness.

Before the dog-days set in, licenses were being granted in Manhattan Borough alone at the rate of one a day for these little hurry-up-and-be-amused booths. They are categorized as “common shows,” thanks to the Board of Aldermen. A special ordinance was passed to rate them under this heading. Thereby they were enabled to obtain a license for $25 for the first year, and $12.50 for the second year. The City Fathers did this before Anthony Comstock and others rose up and proclaimed against them. A full theatrical license costs $500.

An eloquent plea was made for these humble resorts by many “friends of the peepul.” They offered harmless diversion for the poor. They were edifying, educational, and amusing. They were broadening. They revealed the universe to the unsophisticated. The variety of the skipping, dancing, flashing, and marching pictures was without limit. For five cents you were admitted to the realms of the prize ring; you might witness the celebration of a Pontifical mass in St. Peter’s; Kaiser Wilhelm would prance before you, reviewing his Uhlans. Yes, and even more surprising, you were offered a modern conception of Washington crossing the Delaware “acted out by a trained group of actors.” Under the persuasive force of such arguments, was it strange that the Aldermen befriended the nickelodeon man and gave impetus to the craze?

Three hundred licenses were issued within the past year in the Borough of Manhattan alone for common shows. Two hundred of these were for nickelets. They are becoming vastly popular in Brooklyn. They are springing up in the shady places of Queens, and down on Staten Island you will find them in the most unexpected bosky dells, or rising in little rakish shacks on the mosquito flats.

Already statisticians have been estimating how many men, women, and children in the metropolis are being thrilled daily by them. A conservative figure puts it at 200,000, though if I were to accept the total of the showmen the estimate would be nearer half a million. But like all statisticians, who reckon human beings with the same unemotional placidity with which they total beans and potatoes, the statistician I have quoted left out the babies. In a visit to a dozen of these moving-picture hutches I counted an average of ten babies to each theatre-et. Of course they were in their mothers’ or the nurse-girls’ arms. But they were there and you heard them. They did not disturb the show, as there were no counter-sounds, and many of them seemed profoundly absorbed in the moving pictures.

As a matter of fact, some mothers- and all nurse-girls- will tell you that the cinematograph has a peculiarly hypnotic or narcotic effect upon an infant predisposed to disturb the welkin. You will visit few of these places in Harlem where the doorways are not encumbered with go-carts and perambulators. Likewise they are prodigiously popular with the rising generation in frock and knickerbocker. For this reason they have been condemned by the morality crusaders.

The chief argument against them was that they corrupted the young. Children of any size who could transport a nickel to the cashier’s booth were welcomed. Furthermore, undesirables of many kinds haunted them. Pickpockets found them splendidly convenient, for the lights were always cut off when the picture machine was focused on the canvas. There is no doubt about the fact that many rogues and miscreants obtained licenses and set up these little show-places merely as snares and traps. There were many who though they had sufficient pull to defy decency in the choice of their slides. Proprietors were said to work hand in glove with lawbreakers. Some were accused of wanton designs to corrupt young girls. Police-Commissioner Bingham denounced the nickel madness as pernicious, demoralizing, and a direct menace to the young.

But the Commissioner’s denunciation was rather too sweeping. His detectives managed to suppress indecencies and immoralities. As for their being a harbor for pickpockets, is it not possible that even they visit these humble places for amusement? Let any person who desires- metaphorically speaking, of course- put himself in the shoes of a pickpocket and visit one of these five-cent theatres. He has a choice of a dozen neighborhoods, and the character of the places varies little, nor does the class of patrons change, except here and there as to nationality. Having entered one of these get-thrills-quick theatres and imagined he is a pickpocket, let him look about him at the workingmen, at the tired, drudging mothers of bawling infants, at the little children of the streets, newsboys, bootblacks, and smudgy urchins. When he has taken all this in, will not his (assumed) professional impulse be flavored with disgust? Why, there isn’t an ounce of plunder in sight. The pickpocket who enters one of these humble booths for sordid motives must be pretty far down in his calling- a wretch without ambition.

But if you happen to be an outlaw you may learn many moral lessons from these brief moving-picture performances, for most of the slides offer you a quick flash of melodrama in which the villain and criminal are getting the worst of it. Pursuits of malefactors are by far the most popular of all nickel deliriums. You may see snatch-purses, burglars, and an infinite variety of criminals hunted by the police and the mob in almost any nickelet you have the curiosity to visit. The scenes of these thrilling chases occur in every quarter of the globe, from Cape Town to Medicine Hat.

The speed with which pursuer and pursued run is marvellous. Never are you cheated by a mere sprint or straightaway flight of a few blocks. The men who “fake” these moving pictures seem impelled by a moral obligation to give their patrons their full nickel’s worth. I have seen dozen of these kinetoscope fugitives run at least forty miles before they collided with a fat woman carrying an umbrella, who promptly sat on them and held them for the puffing constabulary.

It is in such climaxes as these that the nickel delirium rises to its full height. You and old follow the spectacular course of the fleeing culprit breathlessly. They have seen him strike a pretty young woman and tear her chain-purse from her hand. Of course it is in broad daylight and in full view of the populace. Then in about one-eighth of a second he is off like the wind, the mob is at his heels. In a quarter of a second a half-dozen policemen have joined in the precipitate rush. Is it any wonder that the lovers of melodrama are delighted? And is it not possible that the pickpockets in the audience are laughing in their sleeves and getting a prodigious amount of fun out of it?

The hunted man travels the first hundred yards in less than six seconds, so he must be an unusually well-trained athlete. A stout uniformed officer covers the distance in eight seconds. Reckon the handicap he would have to give Wegers and other famous sprinters. But it is in going over fences and stone walls, swimming rivers and climbing mountains, that you mount the heights of realism. You are taken over every sort of jump and obstacle, led out into tangled underbrush, through a dense forest, up the face of a jagged cliff- evidently traversing an entire county- whirled through a maze of wild scenery, and then brought back to the city. Again you are rushed through the same streets, accompanying the same tireless pack of pursuers, until finally looms the stout woman with the umbrella.

A clerk in a Harlem cigar-store who is an intense patron of the nickelodeon told me that he had witnessed thief chases in almost every large city in the world, not to mention a vast number of suburban town, mining-camps and prairie villages.

“I enjoy these shows,” he said, “for they continually introduce me to new places and new people. If I ever go to Berlin or Paris I will know what the places look like. I have seen runaways in the Boys de Boulong and a kidnapping in the Unter der Linden. I know what a fight in an alley in Stamboul looks like; have seen a papermill in full operation, from the cutting of the timber to the stamping of the pulp; have seen gold mined by hydraulic sprays in Alaska, and diamonds dug in South Africa. I know a lot of the pictures are fakes, but what of that? It costs only five cents.”

The popularity of these cheap amusement-places with the new population of New York is not to be wondered at. The newly arrived immigrant from Transylvania can get as much enjoyment out of them as the native. The imagination is appealed to directly and without any circumlocution. The child whose intelligence has just awakened and the doddering old man seem to be on an equal footing of enjoyment in the stuffy little box-like theatres. The passer-by with an idle quarter of an hour on his hands has an opportunity to kill the time swiftly, if he is not above mingling with the hoi polloi. Likewise the student of sociology may get a few points that he could not obtain in a day’s journey through the thronged streets of the East Side.

Of course the proprietors of the nickelets and nickelodeons make as much capital out of suggestiveness as possible, but it rarely goes beyond a hint or a lure. For instance, you will come to a little hole in the wall before which there is an ornate sign bearing the legend:

FRESH FROM PARIS

Very Naughty

Should this catch the eye of a Comstock he would immediately enter the place to gather evidence. But he would never apply for a warrant. He would find a “very naughty” boy playing pranks on a Paris street- annoying blind men, tripping up gendarmes, and amusing himself by every antic the ingenuity of the Paris street gamin can conceive.

This fraud on the prurient, as it might be called, is very common, and it has led a great many people, who derive their impressions from a glance at externals, to conclude that these resorts are really a menace to morals. You will hear and see much worse in some high-price theatres than in these moving-picture show-places.

In of the crowded quarters of the city the nickelet is cropping up almost a thickly as the saloons, and if the nickel delirium continues to maintain its hold there will be, in a few years, more of these cheap amusement-places than saloons. Even now some of the saloon-keepers are complaining that they injure their trade. On one street in Harlem, there are as many as five to a block, each one capable of showing to one thousand people an hour. That is, they have a seating capacity for about two hundred and fifty, and give four shows an hour. Others are so tiny that only fifty can be jammed into the narrow area. They run from early morning until midnight, and their megaphones are barking their lure before the milkman has made his rounds.

You hear in some neighborhoods of nickelodeon theatre-parties. A party will set out on what might be called a moving-picture debauch, making the round of all the tawdry little show-places in the region between the hours of eight and eleven o’clock at night, at a total cost of, say, thirty cents each. They will tell you afterwards that they were not bored for an instant.

Everything they saw had plenty of action in it. Melodrama is served hot and at a pace the Bowery theatres can never follow. In one place I visited, a band of pirates were whirled through a maze of hair-raising adventures that could not have occurred in a Third Avenue home of melodrama in less than two hours. Within the span of fifteen minutes the buccaneers scuttled a merchantman, made its crew walk the plank, captured a fair-haired maiden, bound her with what appeared to be two-inch Manila rope, and cast her into the hold.

The ruthless pirate captain put his captive on a bread-and-water diet, loaded her with chains, and paced up and down before her with arms folded, a la Bonaparte. The hapless young woman cowered in a corner and shook her clankless fetters. Meanwhile from the poop-deck other pirates scanned the offing. A sail dashed over the horizon and bore down on the buccaneers under full wing, making about ninety knots, though there was scarcely a ripple on the sea. In a few seconds the two vessels were hurling broadsides at each other. The Jolly Roger was shot away. Then the jolly sea-wolfs were shot away. It was a French man-of-war to the rescue, and French man-of-war’s men boarded the outlaw craft. There were cutlass duels all over the deck, from “figgerhead” to taffrail, until the freebooters were booted overboard to a man. Then the fiancé of the fair captive leaped down into the hold and cut off her chains with a jack-knife.

Is it any wonder, when you can see all this for five cents and in fifteen minutes, that the country is being swept by a nickel delirium? An agent for a moving-picture concern informed the writer that the craze for these cheap show-places was sweeping the country from coast to coast. The makers of the pictures employ great troops of actors and take them all over the world to perform. The sets of pictures have to be changed every other day. Men with vivid imaginations are employed to think up new acts. Their minds must be as fertile as the mental soil of a dime-novelist.

The French seem to be the masters in this new field. The writers of feuilletons have evidently branched into the business, for the continued-story moving-picture has come into existence. You get the same characters again and again, battling on the edges of precipitous cliffs, struggling in a lighthouse tower, sleuthing criminals in Parisian suburbs, tracking kidnapped children through dense forests, and pouncing upon would-be assassins with the dagger poised. Also you are introduced to the grotesque and the comique. Thousands of dwellers along the Bowery are learning to roar at French buffoonery, and the gendarme is growing as familiar to them as “the copper on the beat.”

And after all it is an innocent amusement and a rather wholesome delirium.

Comment: Anthony Comstock was renowned moralist who formed the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. This article on New York’s nickelodeons was originally made available online via The Silent Film Bookshelf, a collection of transcriptions of original texts on aspects of film history collated by David Pierce. The site is no longer available, but can be traced in its entirety via the Internet Archive.