Source: Thomas Baird, ‘Speedsters Replace Cowboys’, World Film and Television Progress, vol. 2 no. 12 (March 1938), p. 20

Text: A little over twenty years ago, I started to go to the pictures. I was then a small boy

living in a provincial city. There was quite a ritual about this picture-going. The first requirement was a penny. Pennies only come on Saturdays and, strange coincidence, the “Penny Matinee” came on the same day. Part of the ritual was to forswear the sweetie shops on Saturday morning. This called for severe discipline. It is true that we children had watched the highly dramatic posters all the week. Early on Monday morning the bill poster had pasted them up opposite the school gate. At the eleven o’clock interval we hoisted each other up on to the school wall to see the new posters. From the top of the wall would come shouts of: “It’s a cowboy”, or “It’s about lions”, or “There’s a man in a mask”. Imagination eked out these brief abstracts, and by Saturday excitement was at fever pitch; many a Friday night was sleepless in anticipation. But still it was difficult to pass the sweetie shop and occasionally we succumbed to the temptation of toffee-apples and liquorice straps. Once the precious penny was broken there was nothing for it but to get the greatest value by spending in four shops. But Saturday afternoon was a misery without the matinee.

The second item of the ritual was to be at the picture house fully an hour before the programme commenced. We had to stand in a queue and fight periodically to keep our positions. In the quiet periods we read comics, Buffalo Bills, and Sexton Blakes. Part of the ritual was to swap comics. As a story was finished off a shout went up of: “Swap you comics”, and there was great reaching and struggling to pass the paper to someone else in the queue.

About fifteen minutes to three o’clock the queue grew tense. Comics were stuffed in pockets and the battle to retain a place in the queue started. The struggling and pushing continued for about five minutes. Then the doors opened and a stream of children spilled into the picture house. There was a fight for the best seats. The right of possession meant little, and many a well-directed push slid a small boy from a well-earned seat into the passage.

Occasionally the programme was suitable, and by that I mean interesting to us children. Often, however, the feature was quite meaningless to us. On rare occasions I can remember films like Last Days of Pompeii, Tarzan of the Apes, Cowboy films, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, and the war films, giving us unexpected thrills, but in the main we went for the more comprehensible shorts: Bronco Billy, John Bunny, the Keystone Kops, Ford Sterling, Fatty Arbuckle, then one day a funny little waiter who afterwards we learned to call “Charlie”. Newsreels with soldiers, guns and bursting shells we loved. But we went for one thing above all others — the serial. These were the days of the Clutching Hand, The Exploits of Elaine, The Black Box and The Laughing Mask. Many of the names have faded and been forgotten, but I can recall that the heroine par excellence of all small boys was Pearl White. As Elaine she triumphed week after week, and later, changing with the times, she was Pearl of the Army. The villain of villains was an oriental called Warner Oland and, if I remember rightly, he was the Clutching Hand Himself, but this I will not swear to because these old serials had already learned the trick of making the obviously bad man become good in the last reel. I can remember living through fifteen exciting weeks to learn who the Clutching Hand was: to-day I can’t remember whether it was Oland or not. I seem to be losing my sense of values. Week after week we followed Warner Oland through his baleful adventures. Later he became the malevolent Dr. Fu Manchu. Then for a while I missed him, but, joy of joys, he reappeared as Charlie Chan. It is sad news that he has, perhaps, made his last picture. He has been one of my symbols of a changing cinema; the evil and the nefarious Clutching Hand became in time a prolific and model parent and fought on the side of the angels.

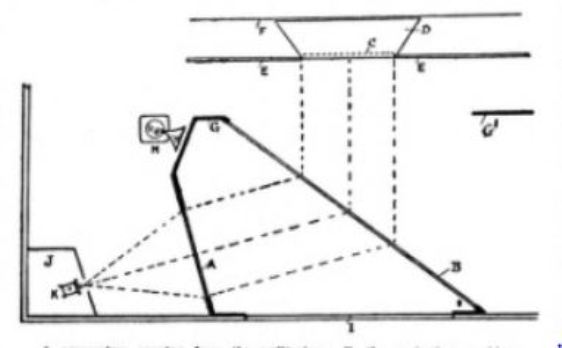

The blonde hero and partner of Pearl White in so many of these episodes was Cr[e]ighton Hale. To us, twenty years ago, he was a superman. He could hang for a week to the edge of a cliff and on the next Saturday miraculously climb to safety. It is perhaps a greater miracle that we, who, in imitation, hung from the washing-house roof, escaped with our lives. But the master mind — the great detective — was Craig Kennedy. That is the name of the character. I doubt if I ever knew the actor’s name and can still remember my astonishment when he turned up as a naval officer in a feature picture. He existed only for us as a detective with no other function than to answer the plea of Cr[e]ighton Hale to discover the whereabouts of Pearl White, or, out of bubbling retorts, to distil the antidote to the bite of the beetle which Warner Oland had secreted in her bouquet of flowers.

Periodically, a rumour ran round. It was whispered in hushed tones in the waiting queue and passed from lip to lip along the rows of excited children. Pearl White was dead. Somebody’s uncle had read in a paper — not an ordinary paper, but an American paper — that she had been killed jumping from an express train on to a motor-cycle. But she kept turning up week after week and this continual resurrection was sufficient to discount each rumour.

Last week I attended a press view of a serial. All the old characters were there. A black-faced villain (Julian Rivero), a thin-lipped henchman (Jason Robarts [sic]), a beautiful schoolboy’s heroine (Lola Lane), a juvenile of strange intelligence and unerring instinct (Frankie Darro) and a hero, smiling, confident, wise, resourceful and athletic (Jack Mulhall). There they all were, and in episode after episode they romped through their tantalizing escapades. The hero leapt from certain death at the end of one reel to equally certain safety at the beginning of the next; falling in mid air at the end of part three, he easily caught hold of a beam at the beginning of part four; flung from a racing car at the end of part four, he landed safely, with never a scratch, in part five. The scream of the heroine in part one turned through tears to laughter in part two; the leer of certain triumph of the villain in part nine turned to a scowl of miserable defeat in part ten.

I was unable to sit through all the hours necessary to reach the satisfactory conclusion which must be inevitable in the final episode, but I am sure that Burn ‘Em Up Barnes kissed Miss Lane in the end, that Frankie Darro achieved his aim both of a college education and being an ace cameraman, that the villains met a sticky end, in a burning racing-car, that Miss Lane never signed that deed which would have ruined her, and which she threatened to sign at least ten times and would have signed, had not Mr. Mulhall, driving at 413.03 miles per hour, arrived in the nick of time. Of all these things I am certain, and who would have it otherwise?

But even with all these familiar items I felt a little strange in the face of this serial. The fatal contract was there; true, the evil leers; true, the heroic athletics; but it was all set in a strange new world. There was no oriental mystery, no cowboy horses, no swift smuggling of drugs, no torture chamber, no shooting, no labs, with fantastic chemistry, no death-ray. It was all set for the new generation of youngsters who read “Popular Mechanics” in the Saturday queues and not for me, with my world of Sexton Blake and Buffalo Bill. The hero is a racing driver. The vital document was not a faded parchment taken from an old sea chest but a cinematograph film taken on a Mitchell. The hidden wealth was not gold but oil. Death came not suddenly by poisoned arrow or slowly in the torture chamber, but fiercely in burning automobiles or lingeringly on the sidewalks after a crash.

Comments: Thomas Baird was a British film journalist and documentary film executive, who worked for the Ministry of Information in the 1940s as its non-theatrical film supervisor. There was no serial named The Clutching Hand in the 1910s or 20s. Instead ‘The Clutching Hand’ was Perry Bennett, the mystery villain played by Sheldon Lewis in The Exploits of Elaine (USA 1914). This was based on the writings of Arthur B. Reeve, whose Craig Kennedy detective character features in the serial, played by Arnold Daly. Pearl White starred as Elaine and Creighton Hale appeared as Walter Jameson in this and the subsequent New Exploits of Elaine (1915) and The Romance of Elaine (1915), the latter of which featured Warner Oland, who became best known for playing the Chinese detective Charlie Chan in the 1930s. The other serials mentioned are The Black Box (USA 1915), Pearl of the Army (1916) and Burn ‘Em Up Barnes (USA 1934). I have not been able to discover what serial is meant by The Laughing Mask. The reference to four shops is because there were four farthings to a penny, and some sweets could be bought for a farthing.

Links: Copy at the Internet Archive (c/o Media History Digital Library)