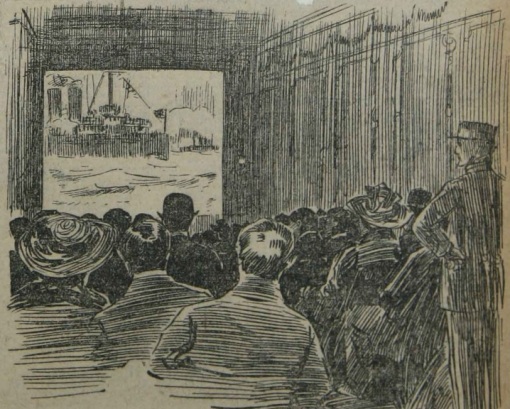

Illustration by Wilson C. Dexter that accompanies the original article

Source: Olivia Howard Dunbar, ‘The Lure of the Films’, Harper’s Weekly, 18 January 1913, pp. 20, 22

Text: Adventures to discover how and where the rest of the world amuses itself are rarely as jocund as they sound. But the adventurer of proper spirit is usually content in witnessing the riotous joy of the multitude, however grimly unmoved his own less facile springs of mirth. Oddly enough, an attempt to share in the delights of “moving pictures,” widely accepted as the most popular of amusements, can scarcely be counted upon to produce even this vicarious satisfaction. For if the adventurer himself gives no sign of being entertained by the “photoplay” or the “art-film,” neither, to his amazement, does the close-packed audience that surrounds him – a fact that is at first inexplicable.

Does all the world demand the “film-show” and then withhold its approval from sheer caprice? And why does it throng so steadily today to the very performance whose lack of stimulus it must have discovered yesterday and the day before?

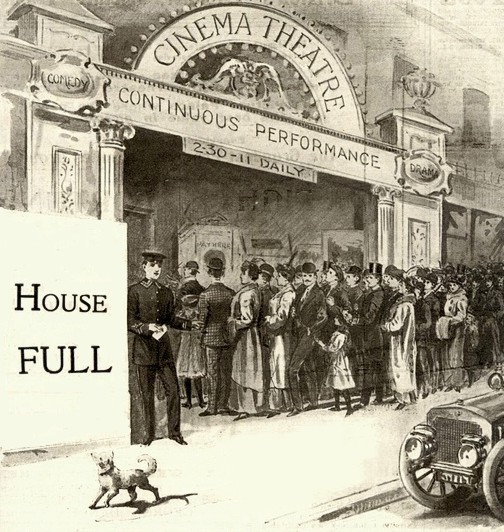

On the other hand, if a random assemblage of this sort gives mysteriously few evidences of active enjoyment, it gives fewer still of displeasure or ennui. To watch it is to discover that it is infinitely tolerant; completely and blessedly immune to boredom. It even betrays no annoyance on being gently approached from behind by some deputy of the management, and sprayed, as a festal touch, with strong. inalienable scent. Daily and hourly – for their patronage is so great that they open either at noon or at nine in the morning — these theaters offer thousands of cases in disproof of all that has been fallaciously said in regard to the restless energy of the American. You wonder how it can be possible, in an alleged busy world, to secure this magnificent total of leisure – to assemble daily, and for long, blank periods, so many people who have nothing to do and who are obviously not worrying about it. Every day, under these roofs, has the stagnant and misleading air of a holiday. And while it may be true that shirking housewives and truant children are never missing, it is nevertheless an interesting fact that three-fourths of the spectators are always men.

Rarely does such an audience betray animation, scarcely ever awareness. Its posture is indifferent and relaxed; its jaws moving unconcernedly in tune with the endlessly reiterated ragtime ground out by some durable automaton — at least, one prefers to believe it an automaton; its dull eyes unresponsively meeting the shadowy grimaccs on the flickering “ film.”

Are these pleasure-seekers resolutely disguising their enjoyment? Or are they, as they appear to be, half asleep? It is true that all the conditions conduce to semi-somnolence – the unbroken whine of the ragtime; the unnatural “continuousness” of the exhibition, hour after hour, without a moment’s interval; the lack of sequence or climax, as of one oddly literal dream succeeding another — varied, at long intervals, by a bolder picture that introduces the strange, noiseless turbulence of nightmare.

In spite of the lack of enthusiasm, there is an indefinable atmosphere of experience and accustomedness. Nobody but yourself is unfamiliar and inquiring. There is rather less suspense and excitement than you will encounter in a trolley-car. You begin to suspect that the phlegmatic audience, having come a great many times before, is quite prepared for the fact that nine-tenths of the programme will be padding and that it does not mind in the least. There is not so much as a change of its expression, much less a sign of applause, as companies of shadow-soldiers are assembled and drilled; parades of a dozen kinds trail their blurred length across the curtain; foreign cities flash out glimpses of their characteristic scenes; ships are launched, cornerstones are laid, medals are presented, and laboratory experiments demonstrating some feature of popular science are painstakingly performed. All “films,” in fact, that may be classed as educational or even indirectly instructive, as well as the occasional ones that are of a genuinely artistic interest, meet with frank but unrcbellious indifference.

For an hour this may continue. Then you are conscious of a stir in the chairs behind you, and a man’s didactic voice begins to enlighten the woman who is with him, in precisely the same fashion that the couple who have sat behind you at the theater all your life have gratuitously explained and perfunctorily listened. You rouse yourself, look about, even glance at the forgotten curtain to discover what it is that has relieved an apathy so general and so profound; and discover that, far from being some unimagined marvel, it is merelv a street scene in New York. And you wonder why the “Film Trust” should go to the trouble of contriving historical “playlets” in costume, through which audiences sleep contentedly, when what really stirs them is the representation of something that they see every day of their lives – the life-size figure of a policeman, a trolley-car, a crowd on Broadway. But this is not, after all, a new phenomenon. The ecstasy experienced by persons of a certain degree of simplicity in recognizing on the stage a familiar object or character has never been explained, although producers must long have realized and catered to it, as an incident in many kinds of drama. It has so often been apparent that audiences betrayed a keener delight in the introduction into a play of a cow or a horse than in the exploits of the most accomplished actor. During one long afternoon of widely varied cinematographic devices, the only genuine success was achieved by a youth who came out before the curtain made a sound like an automobile! This bit of simple realism did wake the sleeping audience from its dreams and gave them an unmistakably poignant pleasure which they expressed without restraint.

These flashes of sympathetic response are rare and fleeting, but may always be evoked by one other element – the broadly farcical. And it is perhaps unnecessary to explain that, the more nearly this unliteral comedy (for realism plays no part_here) approaches that of the comic supplement, the wilder and more immediate its success. An altercation, a practical joke, a chase, are of course the unvarying themes, a chase of anything by anybody, however meaningless, being the acknowledged favorite. Unfailingly popular are the pictured disputes between an impossible mistress and an unnatural servant, in which the maid tumultuously triumphs; or farcical interruptions of the love-making of an ill-suited couple; or rowdy street scenes in which people tumble over each other and somebody gets beaten for an offense he didn’t commit, while the culprit leers from a. neighboring corner. All this is, of course, more or less vulgar, but in the highly unrealistic sense that the comic supplement is vulgar — a harsh, unlovely, shadow-land, repellent, one would suppose, to intelligence and sanity.

The merriment that was set free by the pictured conflict of boy and policeman subsides again into apathy when the first scene in the more ambitious “photoplay” is flashed upon the curtain. For these fragmentary echoes of melodrama seem to be accepted merely as echoes, dim and undisturbing. Their warmed-over quality enables the spectator to remain entirely cool and disillusioned. And yet these plays often present not only the same type of heroine and villain that the old plays did, but the same actors — one would swear to it. The villain’s throwing back his head in cruel, contemptuous laughter is a trick he must have learned and often practised on Fourteenth Street. And the malign deliberation of his walk is full of an ancient theatric significance that could scarcely be felt by any traditionless cub, hired to play in pantomime before the camera. On the other hand, that intemperate use of the telephone that characterizes the moving-picture play was of course unknown to melodrama.

The “Indian play ” – indeed, the Wild West drama generally — is understood to be a commodity that is ordered in large quantities for contemporary audiences; but the result produces no apparent excitement. While a red man discovers a child left alone in a prairie cabin, and, brandishing cruel weapons, pursues the child through various shadow-scenes, the audience contentedly chews its gum. Further scenes are revealed in which the child’s father appears, rescues the child and slays the Indian — but the onlookers are still unmoved. Even the dramatic adventures of the simpering young girl who is menaced by a nondescript villain and rescued at the critical moment by the humble but hitherto neglected suitor are accepted with complete nonchalance. Endangered girlhood is, however, so frequently and persistently presented that the theory must exist that it is a favorite stimulus with these stodgy audiences.

‘There is not so much as a change of expression, much less a sign of applause.’ Illustration by Wilson C. Dexter that accompanies the original article, with caption

Yet these apathetic groups who now appear, except for their occasional bursts of unjoyous mirth, emotionless, are the same men and women who only a few years ago thronged constantly to the melodramas at the urge of what seemed to be an elemental need, the need of wholesome emotional exercise. No audience was ever disappointed in one of these eminently reliable performances; none was ever bored or critical or sleepy. One knew what one had come for and settled down comfortably to enjoy it. It was of relatively little importance whether the central figure in the tangle of love, danger, sacrifice, villainy, heroism, disaster, and triumph was Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model, or Bertha, the Sewing-Machine Girl — the succession of thrills was of practically the same character and intensity. What these audiences unconsciously demanded was an excuse to laugh, weep, pity, resent, condemn, and admire, all in strict conformity with the orthodox moral code; and it was this that was abundantly furnished them. It would surely be a psychological marvel if so deep a need could have vanished as the coincidence of a mere change of fashion in entertainments.

But the best and most satisfying feature of the melodramas was their imaginative scope, their denial of logical limitations. The simple, normal mind while it has felt a childlike delight in the occasional realistic detail, has probably always been charmed by the theater in proportion as its spectacle, as a whole, transcended reality. A world as unfettered as the world of faery, whose characters should have the shape and speech of the ordinary wage-earner, would have at any time a compelling appeal. “What attracted me so strongly to the theater,” Wagner says, speaking of his childhood, “was … the fascinating pleasure of finding mvself in an entirely different atmosphere, in a world that was purely fantastic and often gruesomely attractive. Thus to me … some costume or a characteristic part of it seemed to come from another world, to be in some way as attractive as an apparition.” There is no doubt that this is the expression of a universal experience; and that if a sensitive, impressionable child of six or seven could define and express the emotions (too vaguely recalled by the adult) aroused by its first theater, this would form a human document of thrilling interest. And it may be that melodrama at its best supplied multitudes of adult children with an approximation of this delicious and memorable experience of infancy.

In comparison with the popular drama that it has succeeded and supplanted, the motion picture of course provides little or no emotional outlet. It is far from attempting to “purge with pity and terror” the casual multitudes that it attracts. In most cases the interest that it excites, when it excites any, is shallow, fleeting, two-dimensional, like the pictures themselves. It offers no illusion and no mystery. What is left to those who have had to accustom themselves to this thin and unsatisfying form of emotion, but to acquire, as they have, a self-protective surface of apparent torpor?

It is easy, of course, to recall conspicuously exceptional cases. There is now and then a feverish desire to see the pictured record of some current event of especial interest, particularly when it has to do with sports. But the kind of excitement that would be aroused by the records of a baseball or football game is a very special thing, and is infinity [sic] removed from the mere normal desire for amusement. Yet it is fully shared, as everybody knows, by sophisticated childhood. Indeed, the overpowering desire felt by youthful East Side citizens to see certain celebrated “movies” has more than once led them into tragic difficulty. Not many months ago, just after a much-advertised prize-fight, two little boys, whose uncontrollable longing for the admission fee to a picture-hall had led them to upset a grocer’s display and barter his goods independently, were brought to the Children’s Court. “The price of admittance was five cents?” inquired the judge, examining them. The smaller boy, who was very small indeed, quickly raised his thin, tense face. “Oh, but it was ten cents to see the big fight, judge!” he cried, hoarsely, the tremendous intensity of his manner and expression at once defining the almost irresistible character of his temptation and what he felt to be the manly magnitude of his crime.

But even though its imagination starve, a disaster of which it can scarcely be conscious, it is not difficult to understand why the vast, simple, unexigent public so faithfully follows up the moving picture. Almost any institution that cost so little would probably be patronized, even though the most it did was to provide a convenient and often comfortable lounging place, and, in the poorer quarters of the city, to provide an excuse for social contact. After all, there is no question but that the equivalent of a nickel is usually supplied. Beyond this, there is the fascination of never knowing what one is going to see, which is a far greater lure than an exact knowledge of what is forthcoming. But its strongest hold must be the fact that it makes no demand whatever upon its audiences, requiring neither punctuality — for it has no beginning — nor patience — for it has no end — nor attention — for it has no sequence. No degree of intelligence is necessary, no knowledge of our language, nor convictions nor attitude of any kind, reasonably good eyesight being indeed the only requisite. In the world of amusement, no line of less resistance than this has surely yet been offered.

Comment: Olivia Howard Dunbar (1873-1953) was an American biographer and writer of ghost stories.