Source: Ursula Bloom, Youth at the Gate (London: Hutchinson, 1959)

Text: On Tuesday, August the fourth, when we were already halfway through the evening programme at the White Palace, Mr. Clements returned and started to talk again. He said that he wanted the national anthems of all countries who would be our allies to be played in a kind of pot-pourri at the end of the evening, ours as the final one.

I did not think it was a good idea. Already innumerable countries were involved, some with very long national anthems, and it would take a time to compose and to play, when all the audience asked was to be allowed to go home.

He looked at me with gaunt dark eyes on either side of a big nose which was like an eagle’s beak He was horribly worried, we knew that because his finger-nails were bitten to the quick (one of his nastier habits) and last week one of the girls had noticed that they were actually bleeding.

Mr. Clements was on the Stock Exchange (the cinema being merely a hobby), and with war coming he saw disaster ahead It is pathetic that at the time I did not realize that his wife had a daughter by a previous marriage to a German, a girl born deaf and dumb, and both of them were in agony lest Olga would be taken from them and put into a detention camp. I had never heard of such a place.

Earlier this evening Brooker the commissionaire had gone. A policeman had come for him, which alone caused some perturbation, but he was an old soldier on the Reserve. We wished him well, and those who could gave him something ‘for luck’, there seemed little time for goodbyes. This had brought the war considerably closer. Brooker, a very ordinary little man, who had never even been particularly brave with the drunks, suddenly glittered into something of a hero.

‘God only knows what’ll happen,’ said Mr. Clements in anxiety. ‘It’ll be the end of the world as we know it. One thing is certain, England’ll never be quite the same again.’

I was contemptuous. I thought he was cowardly, something to be despised in this moment of thrill. If we went to war (and oh, how I hoped we should!), England would rise with a glory never before achieved.

‘Maybe it’ll be nicer than you think?’ I suggested as I wrestled with ‘Poet and Peasant’ on the cottage piano.

‘You’re just a silly little girl! You don’t know a thing about it, and you’d better hold your tongue,’ he snapped, then swept out through the curtains, which at the start had been second-hand, leaving me with a haze of their dust and facing the nastier bits of ‘Poet and Peasant’.

The ‘Pathé Gazette’ flickered across the screen with pictures of the Reserves being called up, to be greeted with violent applause from the twopennies. A destroyer put out from Harwich harbour. A slide told the audience that so far – my tin clock told me it was nine o’clock, just before the ‘big picture’ – Germany had not replied to our ultimatum, and the twopennies booed.

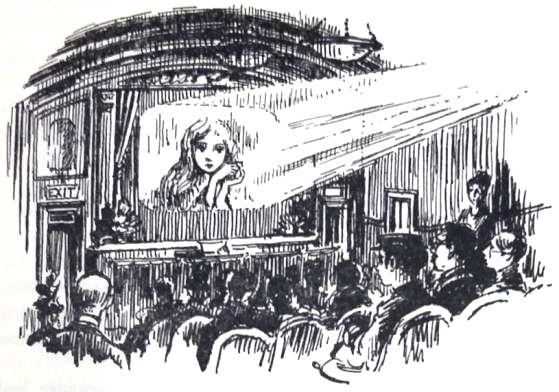

The cinema darkened again, just above me lights played on to the screen, and the tin clock (one-and-sixpence) on the piano top began to tick away the last vital minutes of the old regime. At the dramatic moments of one’s life one does not recognize the tensity of emotional crisis. Sitting there playing for Mary Pickford was just another night in my life. No more.

When the end came I played the national anthems, but the audience did not stay, for they were eager to rush out and hear if we were really at war or not. Not yet. I closed the piano lid, and pushed the borrowed music into a box, for at all costs we had to keep that clean or the shop on Hollywell Hill wouldn’t take it back next Monday. I went through the deserted foyer, up shoddy stairs to where Teddy was waiting with his chocolate tray to get it checked. As nobody else came to do it, he and I achieved this together.

The two girl attendants pulled on coats which hung on a wall hook, the only attempt at a ladies’ room that we had. There was no lavatory of any kind and in emergencies one had to go up to the station which was a considerable way off. Any natural need of this kind was vulgar and could not be mentioned. Mother always said it was better than in the eighties when one was prepared to die rather than admit that nature could no longer contain itself, and some people had died, she vowed.

I went downstairs again into the foyer which advertised next week’s programme in big colourful posters to catch the eye. We should be running Les Miserables, a picture I had selected. Montie was waiting, in the green suit of the era, and with a stick.

‘Have we gone to war?’ I asked.

He didn’t know.

Comments: Ursula Bloom (1892-1984) was a highly-prolific British novelist. In her various memoirs, of which Youth at the Gate is only one, she provides detailed accounts of the time she spent as a pianist at the White Palace cinema in Harpenden, just before the First World War.