Source: Leslie Halliwell, Seats in All Parts (London: Granada, 1985), pp. 54-56

Text: … the Lido in Bradshawgate, as unprepossessing an unVenetian a building as could be imagined despite its gondola-filled proscenium frieze. Financed by a small Salford-based circuit, it was little more than a cheap shell. The foyer was bare and cramped, and the centre stalls exists were by crash doors which opened from the auditorium straight out into the side alleys, sometimes drenching the adjacent customers in rain or snow.

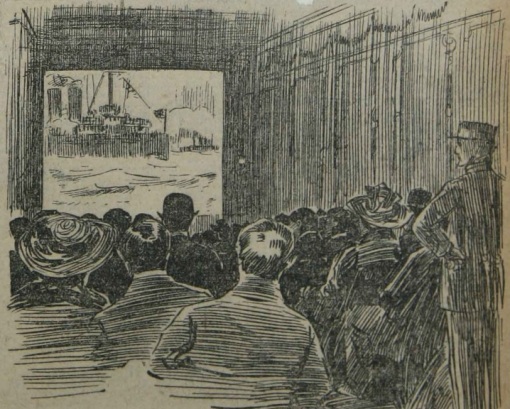

But we were unaware of such inconveniences on the Saturday in 1937 when we queued for the gala opening. For some reason the attraction chosen for that one night only was a revival of Jessie Matthews in Evergreen, very welcome but quite uneventful, since we had previously seen it at the Hippodrome. The place nevertheless was mobbed, and we found ourselves in a low point of the front stalls from which it was difficult for me to see more than the top half of the screen over the heads of the people in front. I was comforted, however, by a handful of sample packets of a confectionery, then new, called Maltesers: the usherettes were practically throwing them at everyone who came in, and I grabbed as many as I could from the tray on the way to my seat.

We went again on Monday to see the Lido’s first première, which was Song of Freedom, staring Paul Robeson. It was enjoyable enough while the star held sway, and I responded to his voice as to no one else’s since Al Jolson, who seemed unaccountably to have retired from the screen; but by now we had discovered two of the Lido’s failings. The first was its long, long intervals for ice cream sales, drastically curtailing the supporting programme we expected; the second was an even longer non-attraction called Younger’s Shoppers’ Gazette, a compilation of crude advertising filmlets (I once counted twenty-eight on the one reel). This was certainly not value for money, especially since the Lido was also the proud possessor of a Christie organ, and the interlude for this could stretch the gap between solid celluloid items to as much as thirty-five minutes. Though it had the advantage of a phantom piano attachment, the Lido organ did not rise from the orchestra pit as we expected, nor did it change colour as it came. From some of the side seats you could see it waiting in the wings throughout the performance, and since the main curtain hung slightly short, front stalls patrons could count the feet of the men who pushed it on stage at the appropriate moment. This musical marvel was operated by one Reginald Liversidge, an eager-to-please young man with a gleaming smile and a fine head of skin; his natty tailcoat and graceful manners probably endeared him to the matrons, but not to me. So far as I was concerned, his slide-accompanied concerts of ‘Tchaikovskiana’ were just one more nail in the coffin of a disappointing venue in which I had expected to spend many delightful evenings.

And so I was not impelled, in the years before the 1939 war, to visit the Lido very often. Its schedulers did not have the booking power of the established cinemas, and certainly not of the new Odeon which was to menace them all. It was too often to take the cheapest programme available, and I was happiest when it settled for a re-issue. One such attraction was the 1931 Fredric March version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which my mother wanted to see again, having been impressed by it when I was still in swaddling clothes. It was my first experience, in our well-behaved town, of an audience cat-calling and rough-housing during a performance. Mum said comfortingly that they only did it to prove they were not scared by Jekyll’s transformations into Hyde; I was, but tried not to show it, my fear being tempered by a burning desire to wear, when I grew up, a dress cape, cane and top hat just like Mr March’s. I realize now that this superbly crafted film, by far the best version of the story, is not only horrifying but surprisingly one-track-minded in the matter of sex, and therefore not at all a suitable entertainment for a boy of tender years; nonetheless what I most remember from that long-ago evening is how lustrous and dramatic it was to look at. Mum anxiously watched my reactions to the shock moments and, since I showed no ill effects, took me along a few weeks later to see the Lido’s ‘double thrill bill’ consisting of re-issues of The Old Dark House and The Invisible Man. This time, to our astonishment, we were forestalled by the burly commissionaire in the second-hand uniform, who informed us between pursed lips that Children were no Admitted. My mother pointed out that both films had ‘A’ certificates, not ‘H’, and that she regularly took me to ‘A’ pictures, but argument proved useless, and we could only conclude that this was an entirely unofficial rule drawn up by the management either for the public good or (more likely) to drum up business during a dull week. Adamant, the commissionaire repeatedly tapped a hanging notice on which the words ADULTS ONLY had been inscribed in shaky green lettering. Although, he assured us confidentially, he had seen both pictures and wouldn’t give you that (he snapped his fingers) for their horror content, he was powerless to help us, and could only suggest that we went round the corner to the Theatre Royal where Old Mother Riley was showing. His sister had described it as a real good laugh. Disconsolately, we took his advice; but I don’t remember laughing much: the rather primitively filmed knockabout failed to capture the instinctive zest of Lucan and MacShane’s crockery-smashing stage act which I had seen at the Grand on one recent Saturday night.

Comments: Leslie Halliwell (1929-1989) was a film historian and programme buyer for ITV and Channel 4. Seats in All Parts is his memoir of cinemagoing, including his Bolton childhood. ‘A’ certificates were introduced in 1912 and stood for ‘Adult’; from 1923 a child attending an ‘A’ film had to be accompanied by an adult. ‘H’ certificates, for Horror, were introduced by the British Board of Film Censors in 1932, to be replaced by the X certificate in 1951. The Lido cinema opened in March 1997 and closed in 1998, by which time it was called the Cannon Cinema. The site is now occupied by a block of flats. The films recalled by Halliwell are Evergreen (UK 1934), Song of Freedom (UK 1936), The Old Dark House (USA 1932), The Invisible Man (USA 1933) and Old Mother Riley (UK 1937). Younger’s Shopper’s Gazette was produced by Younger Publicity Service and ran from the 1920s to the 1940s. An example can be seen on the website of the Media Archive for Central England.