Source: O. Winter, ‘The Cinematograph’, The New Review, May 1896, pp. 507-513

Text: Life is a game played according to a set of rules – physical, moral, artistic – for the moment ironbound in severity, yet ever shifting. The heresy of to-day is to-morrow‘s dogma, and many a martyr has won an unwilling crown for the defence of a belief, which his son’s boot-black accepts as indisputable. The tyranny of the arts, most masterful of all, seldom outlasts a generation; time brings round an instant revenge for a school’s contempt of its predecessor; and all the while Science is clamorously breaking the laws, which man, in his diffidence, believes to be irrefragable.

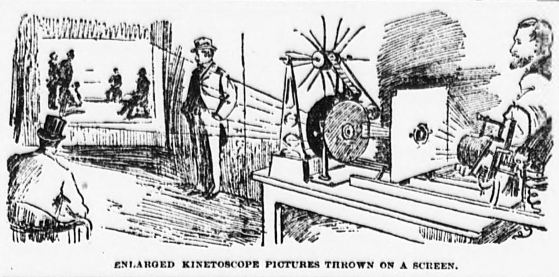

When the first rude photograph was taken, it was already a miracle; but stability was the condition of its being, and the frozen smirk of an impossible tranquillity hindered its perfection. Even the “snap-shot,” which revealed poses indiscoverable to the human eye, was, at best, a mere effect of curiosity, and became, in the hands of Mr. Muybridge and others, the instrument of a pitiless pedantry. But, meantime, the moving picture was perfected, and, at last, by a skilful adaptation of an ingenious toy, you may contemplate life itself thrown moving and alert upon a screen. Imagine a room or theatre brilliant with electric lights and decorated with an empty back-cloth. Suddenly the lights are extinguished, and to the whirring sound of countless revolutions the back-cloth quivers into being. A moment since it was white and inanimate; now it bustles with the movement and masquerade of tremulous life. Whirr! And a train, running (so to say) out of the cloth, floats upon your vision. It draws up at the platform; guards and porters hustle to their toil; weary passengers lean through the window to unfasten the cumbrous door; sentimentalists hasten to intercept their friends; and the whole common drama of luggage and fatigue is enacted before your eyes. The lights leap up, and at their sudden descent you see upon the cloth a factory at noon disgorging its inmates. Men and women jostle and laugh; a swift bicycle seizes the occasion of an empty space; a huge hound crosses the yard in placid content; you can catch the very changing expression of a mob happy in its release; you note the varying speed of the footsteps; not one of the smaller signs of human activity escapes you. And then, again, a sudden light, and recurring darkness. Then, once more, the sound and flicker of machinery; and you see on the bare cloth a tumbling sea, with a crowd of urchins leaping and scrambling in the waves. The picture varies, but the effect is always the same – the terrifying effect of life, but of life with a difference.

It is life stripped of colour and of sound. Though you are conscious of the sunshine, the picture is subdued to a uniform and baffling grey. Though the waves break upon an imagined shore. they break in a silence which doubles your shrinking from their reality. The boys laugh with eyes and mouth-that you can see at a glance. But they laugh in a stillness which no ripple disturbs. The figures move after their appointed habit; it is thus and not otherwise that they have behaved yesterday and will behave to-morrow. They are not marionettes, because they are individuals, while a marionette is always generalised into an aspect of pity or ridicule. The disproportion of foreground and background adds to your embarrassment, and although you know that the scene has a mechanical and intimate correspondence with truth, you recognise its essential and inherent falsity. The brain and the eye understand not the process of the sensitive plate. They are ever composing, eliminating, and selecting, as if by an instinct. They work far more rapidly than the most elaborate mechanism. They discard one impression and take on another before the first has passed the period of its legitimate endurance. They permit no image to touch them without alteration or adaptation. The dullest eye, the deafest ear, has a personality, generally unconscious, which transforms every scene, and modifies every sound. A railway station, for instance, is a picture with a thousand shifting focuses. The most delicate instrument is forced to render every incident at the same pace and with the same prominence, only reserving to itself the monstrous privilege of enlarging the foreground beyond recognition. If you or I meet an arriving train, we either compose the scattered elements into a simple picture, and with the directness, distinguishing the human vision from the photographic lens, reject the countless details which hamper and confuse our composition, or we stand upon the platform eager to recognise a familiar face. Then the rest of the throng, hastily scanned, falls into a shadowy background. Thus in the moving picture, thrown upon the screen, the crowd is severally and unconsciously choosing or rejecting the objects of sight. But we find the task impossible. The grey photograph unfolds at an equal pace and with a sad deliberation. We cannot follow the shadows in their enthusiasm of recognition; the scene is forced to trickle upon our nerves with an equal effect; it is neither so quick nor so changeful as life. From the point of view of display the spectacle fails, because its personages lack the one quality of entertainment: self-consciousness. The ignorant man falls back upon the ancient wonderment. “Ain’t it lifelike!” he exclaims in all sincerity, though he possesses the faculty of comparison but roughly developed, and is apt to give an interpretation of reality to the most absurd symbols.

Here, then, is life; life it must be because a machine knows not how to invent; but it is life which you may only contemplate through a mechanical medium, life which eludes you in your daily pilgrimage. It is wondrous, even terrific; the smallest whiff of smoke goes upward in the picture; and a house falls to the ground without an echo. It is all true, and it is all false. “Why hath not man a microscopic eye?” asked Pope; and the answer came prosaic as the question: “The reason it is plain, he’s not a fly.” So you may formulate the demand: Why does not man see with the vision of the Cinematograph? And the explanation is pat: Man cannot see with the mechanical unintelligence of a plate, exposed forty times in a second. Yet such has ever been the ambition of the British painter. He would go forth into the fields, and adjust his eyes to the scene as though they were a telescope. He would register the far-distant background with a monstrous conscientiousness, although he had to travel a mile to discover its qualities. He would exaggerate the foreground with the clumsy vulgarity of a photographic plate, which knows no better cunning, and would reveal to himself, with the unintelligent aid of a magnifying glass, a thousand details which would escape the notice of everything save an inhuman machine. And while he was a far less able register of facts than the Cinematograph, he was an even worse artist. He aimed at an unattainable and undesirable reality, and he failed. The newest toy attains this false reality without a struggle. Both the Cinematograph and the Pre-Raphaelite suffer from the same vice. The one and the other are incapable of selection; they grasp at every straw that comes in their way; they see the trivial and important, the near and the distant, with the same fecklessly impartial eye. And the Pre-Raphaelite is the worse, because he is not forced into a fatal course by scientific necessity. He is not racked upon a machine that makes two thousand revolutions in a minute, though he deserves to be. No; he pursues his niggled path in the full knowledge of his enormity, and with at least a chance, if ever he opened his eye, of discovering the straight road. The eye of the true impressionist, on the other hand, is the Cinematograph’s antithesis. It never permits itself to see everything or to be perplexed by a minute survey of the irrelevant. It picks and chooses from nature as it pleaseth; it is shortsighted, when myopia proves its advantage; it can catch the distant lines, when a reasoned composition demands so far a research. It is artistic, because it is never mechanical, because it expresses a personal bias both in its choice and in its rejection. It looks beyond the foreground and to the larger, more spacious lines of landscape. Nature is its material, whereas Fred Walker and his followers might have been inspired by a series of photographic plates.

Literature, too, has ever hankered unconsciously after the Cinematograph. Is not Zola the M. Lumière of his art? And might not a sight of the Cinematograph have saved the realists from a wilderness of lost endeavour? As the toy registers every movement without any expressed relation to its fellow, so the old and fearless realist believed in the equal value of all facts. He collected information in the spirit of the swiftly moving camera, or of the statistician. Nothing came amiss to him, because he considered nothing of supreme importance. He emptied his notebooks upon foolscap and believed himself an artist. His work was so faithful in detail that in the bulk it conveyed no meaning whatever. The characters and incidents were as grey and as silent as the active shadows of the Cinematograph. M. Zola and M. Huysmans (in his earlier incarnation) posed as the Columbuses of a new art, and all the while they were merely playing the despised part of the newspaper reporter. They fared forth, notebook in hand, and described the most casual accidents as though they were the essentials of a rapid life. They made an heroic effort to strip the brain of its power of argument and generalisation. They were as keenly convinced that all phenomena are of equal value as is the impersonal lens, which to-day is the Academician’s best friend. But they forget that the human brain cannot expose itself any more easily than the human eye to an endless series of impartial impressions. For the human brain is not mechanical: it cannot avoid the tasks of selection and revision, and when it measures itself: against a photographic apparatus it fails perforce. It is the favourite creed of the realists that truth is valuable for its own sake, that the description of a tiresome hat or an infamous pair of trousers has a merit of its own closely allied to accuracy. But life in itself is seldom interesting – so much has been revealed by photography; life, until it be crystallised into an arbitrary mould, is as flat and fatuous as the passing bus. The realist, however, has formulated his ambition: the master of the future, says he, will produce the very gait and accent of the back-parlour. This ambition may already be satisfied by the Cinematograph, with the Phonograph to aid, and while the sorriest pedant cannot call the result supremely amusing, so the most sanguine of photographers cannot pronounce it artistic. At last we have been permitted to see the wild hope of the realists accomplished. We may look upon life moving without purpose, without beauty, with no better impulse than a foolish curiosity; and though the spectacle frightens rather than attracts, we owe it a debt of gratitude, because it proves the complete despair of modern realism.

As the realistic painter, with his patient, unspeculative eye bent upon a restless foreground, produces an ugly, tangled version of nature, so the disciple of Zola perplexes his indomitable industry by the compilation of contradictory facts. Not even M. Zola himself, for all his acute intelligence, discovered that Lourdes, for instance, was a mere flat record. By the force of a painful habit, he differentiated his characters; he did not choose a single hero to be the mule (as it were), who should sustain all the pains and all the sins of the world. No, he bravely labelled his abstractions with names and qualities, but he played the trick with so little conviction, that a plain column and a half of bare fact would have conveyed as much information and more amusement. Now, M. Zola has at least relieved the gloom of ill-digested facts by adroitly-thrown pétards. When you find his greyness at its greyest, he will flick in a superfluous splash of scarlet, to arouse you from your excusable lethargy. But in America, where even the novel may be “machine-made,” they know far better than to throw pétards. Their whole theory of art is summed up in the Cinematograph, so long as that instrument does its work in such an unexciting atmosphere as the back-yard of a Boston villa. Life in the States, they murmur, is not romantic. Therefore the novel has no right to be romantic. Because Boston is hopelessly dull, therefore Balzac is an impostor. For them, the instantaneous photograph, and a shorthand clerk. And, maybe, when the historian of the future has exhausted the advertisement columns of the pompous journals, he may turn (for statistics) to the American novel, first cousin, by a hazard, to the Cinematograph.

The dominant lesson of M. Lumière’s invention is this: the one real thing in life, art, or literature, is unreality. It is only by the freest translation of facts into another medium that you catch that fleeting impression of reality, which a paltry assemblage of the facts themselves can never impart The master quality of the world is human invention, whose liberal exercise demonstrates the fatuity of a near approach to “life.” The man who invents, may invent harmoniously; he may choose his own key, and bend his own creations to his imperious will. And if he be an artist, he will complete his work without hesitancy or contradiction. But he who insists upon a minute and conscientious vision, is forthwith hampered by his own material, and is almost forced to see discordantly. Hence it is that M. Zola is interesting only in isolated pages. His imagination is so hopelessly crippled by sight, that he cannot sustain his eloquence beyond the limit of a single impression. Suppose he does astonish you by a flash of entertainment, he relapses instantly into dulness, since for him, as for the Cinematograph, things are interesting, not because they are beautiful or happily combined, but because they exist, or because they recall, after their clumsy fashion, a familiar experience.

Has, then, the Cinematograph a career? Artistically, no; statistically, a thousand times, yes. Its results will be beautiful only by accident, until the casual, unconscious life of the streets learns to compose itself into rhythmical pictures. And this lesson will never be learned outside the serene and perfect air of heaven. But if only the invention be widely and properly applied, then history may be written, as it is acted. With the aid of these modern miracles, we may bottle (so to say) the world’s acutest situations. They will be poured out to the students of the future without colour and without accent, and though their very impartiality may mislead, at least they will provide the facts for a liberal judgment. At least they will give what an ingenious critic of the drama once described as “slabs of life.” For the Cinematograph the phrase is well chosen; but for Ibsen, who prompted its invention, no phrase were more ridiculous. For whatever your opinion of Hedda Gabler, at least you must absolve its author from a too eager rivalry with M. Lumière’s hastily-revolving toy.

And now, that Science may ever keep abreast of literature, comes M. Röntgen’s invention to play the part of the pyschologist [sic]. As M. Bourget (shall we say?) uncovers the secret motives and inclinations of his characters, when all you ask of him is a single action, so M. Röntgen bids photography pierce the husk of flesh and blood and reveal to the world the skeletons of living men. In Science the penetration may be invaluable; in literature it destroys the impression, and substitutes pedantry for intelligence. M. Röntgen, however, would commit no worse an outrage than the cure of the sick and the advancement of knowledge. Wherefore he is absolved from the mere suspicion of an onslaught upon art. But it is not without its comedy, that photography’s last inventions are twin echoes of modern literature. The Cinematograph is but realism reduced to other terms, less fallible and more amusing ; while M. Röntgen’s rays suggest that, though a too intimate disclosure may be fatal to romance, the doctor and the curiosity-monger may find it profitable to pierce through our “too, too solid flesh” and count the rattling bones within.

Comments: O. Winter was an occasional writer for art and culture journals in the 1890s. I have not been able to trace his full name. The essay was written after seeing an exhibition of the Lumière Cinématographe, which debuted in the United Kingdom on 20 February 1896. A number of Lumière films are suggested by the text, including Arrivée d’un train and La Sortie des Usines Lumière (Workers Leaving the Factory). Those mentioned in the text are the novelists Emile Zola, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Honoré Balzac and Paul Bourget, playwright Henrik Ibsen, Pre-Raphaelite painter Fred Walker, and photographer Eadweard Muybridge. Wilhelm Röntgen discovered what would soon become known as X-rays in 1895; X-rays, or Röntgen rays, would frequently be exhibited alongside motion pictures in the late 1890s.