Source: Verne Morgan, Yesterday’s Sunshine: Reminiscences of an Edwardian Childhood (Folkestone: Bailey Brothers and Swinfen, 1974), pp. 122-126

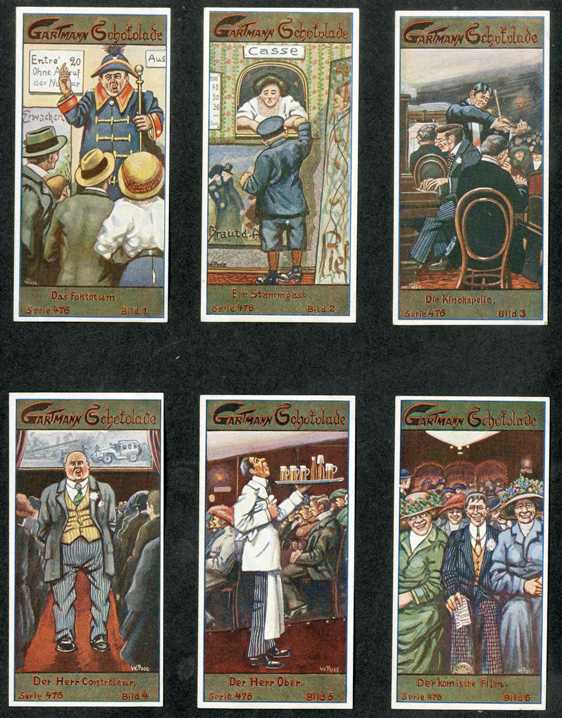

Text: The Moving Pictures, as we called them, first came to Bromley when I was about seven. They made their début at the Central Hall, and the performances took place on Friday nights. There were two houses, one at five o’clock for the children and one at seven for the grown-ups. The programmes lasted approximately one hour, and consisted of a succession of short films. Indeed some of them would last no longer than three or four minutes and there would be an appreciable wait in between while the man in the box got busy threading the next reel.

The Central Hall was a vast place with a huge gallery encircling it. It was used mostly for political meetings and the like, and quite often a band concert would be held there too. But it also had a pronounced ecclesiastical leaning and the man who owned it belonged in some way to the church and was avidly religious. He was an elderly man and wore pince-nez spectacles to which were attached a long black cord. He was a man of extremely good intentions and loved to stand upon the platform making long speeches spouting about them. Unfortunately, he had the most dreadful impediment and it was quite impossible to understand a word he said. But I well remember the enthusiastic claps he got when he eventually sat down, not because we had appreciated what he said so much as the fact that he had at last finished. The film programme could then begin.

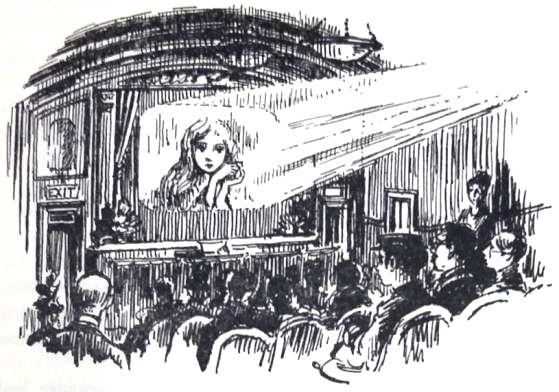

The operating box was a temporary affair, and was perched up at the rear of the gallery. I used to get a seat as close to it as possible so that I could see how it was all done. The lighting was effected by a stick of black carbon, about the size of a piece of chalk, which lit up the small box with a brilliant blueish-white light and had a blinding effect if you looked right at it. Occasionally it would burn low and the operator would push it up a bit; this would be reflected by the density of light on the screen. The screen itself was also of a temporary nature, it was in fact little more than a large white sheet weighted at the bottom to keep it taut. Any movement close to it would cause it to wobble, and the picture would go a little peculiar. We were not critical of such minor details. The very fact that the picture moved was enough to satisfy us.

As each small reel was finished the operator would place it outside for re-winding, his box being of limited dimensions. On account of this I was able to study the technique as to how the pictures appeared to move. It was so simple I could hardly believe it. I told my Brother about it; I told my Mother about it; I told lots of people about it. But no one believed me. So, to prove myself right, I set about editing a film on my own account. I drew a succession of pictures in pencil on the bottom of a hymn book in church. Each one was just that little bit different, so that when the pages were flicked over the overall picture appeared to move. This technique, in ‘flicker’ form, has, of course, been used in many ways since then, but at the time it was entirely my own idea, and I was middling proud of it. I can’t say that anybody was particularly impressed, but at the time it thrilled me beyond description. In due course I pictorialised all the hymn books I could lay my hands on, during the sermon and other breaks in the church service. They consisted mostly of football matches with someone scoring a goal. Or it might be a boxing match with someone getting knocked out. Or an exciting race with a hectically close finish. Anything that inspired my sporting instincts was in course of time recorded in the hymn books of St. Luke’s Church, Bromley. I have often wondered since what the effect must have been on the boy who eventually took my seat in the choir pew when he found what he had inherited. I can only hope that he had as much enjoyment out of watching animated pictures as I had got out of drawing them.

The Central Hall was situated close to the top of Bromley Hill, nearly three miles from where we lived. It was a long walk for small legs, and there was no public transport at that time. Yet, whatever the weather, we never missed. Every Friday, shortly after school hours, a swarm of happy-faced youngsters were to be seen all heading in the same direction. The Central Hall had become the centre of a new culture. But, as yet, only the school kids had caught on to it.

Then quite suddenly, the Grand Theatre in Bromley High Street, which up till then had housed nothing more spectacular than stage dramas of the “Maria Marten” and “Sweeney Todd” kind, put up the shutters and announced that in future Moving Pictures would take over. They would be put on once nightly with a full programme of films. A new firm moved in calling itself Jury’s. The old Grand was given a face-lift and transformed into a picture house.

This was revolutionary indeed.

The grown-ups were sceptical. But the programmes were of a higher standard than those at the Central Hall, and would sometimes have a two-reeler as the star attraction. The films began to take on a more realistic angle, with interesting stories, love scenes, cowboys and Indians, exciting battles and lots of gooey pathos.

People began to go.

When they announced a showing of the famous story “Quo Vadis” in seven reels, all Bromley turned out to see it. Even my father condescended, and grumbled volubly because he had to “line up” to get it (the word “queue” had not yet come into circulation).

It was the beginning of a new era. Very soon a place was built in the High Street, calling itself a cinema. Moving pictures were firmly on the map, and shortly to be called films. We watched with astonishment as the new building reached completion and gave itself the high-flown title of “The Palaise [sic] de luxe”.

Most of us pronounced it as it was spelt, “The Palace de lux”, but my cousin Daisy, who was seventeen and having French lessons twice a week, pronounced it the “Palyay dee Loo”. And she twisted her mouth into all sorts of shapes when she said it.

That being as it may, the Palaise de Luxe put on programmes that pulled in the crowds from far and near, and it wasn’t long before they engaged a pianist to play the piano while the films were in progress. I remember him well. A portly gentleman who hitherto had earned a precarious living playing in local pubs. He soon got into his stride and began to adapt his choice of music to the particular film that was being shown. If it was a comedy he would play something like “The Irish Washerwoman”; if it was something sad, he would rattle off a popular number of the day like, “If your heart should ache awhile never mind”, and if it was a military scene, he would strike up a well-known march. The classic example came when a religious film was presented and we saw Christ walking on the water. He immediately struck up a few bards of “A life on the ocean wave”.

Later on, all cinemas worthy of the name included a small orchestra to accompany the films, and in due course, a complete score of suitable music would be sent with the main feature film so as to give the right effect at the right moment.

The Palaise de Luxe was indeed a palace as far as we were concerned. We sat in plush tip-up seats and there were two programmes a night. Further, you could walk in any old time and leave when you felt like it. Which meant, of course, that you could, if you so desired, be in at the start and watch the programme twice through (which many of us did and suffered a tanning for getting home late). It was warm and cosy, and there was a small upper circle for those who didn’t wish to mix!

The projector was discreetly hidden away behind the back wall up in the circle, and no longer could you see the man turning the handle. We became conscious for the first time of the strong beam of light that extended from the operating box to the screen. It was all so fascinating and mysterious. The screen, too, was no longer a piece of white material hanging from the ceiling, it was built into the wall, or so it appeared, and it was solid, so that no amount of movement could make it wobble.

It quickly became the custom to visit the cinema once a week. It was the “in” thing, or as we said in those days, it was “all the rage”.

We learnt to discriminate. My Brother and I became infatuated with a funny little man who was just that bit different from the others. His tomfoolery had a “soul” we decided, and whereas we smiled and tittered at the others comics, we roared our heads off with laughter whenever this one came on the screen. We went to a great deal of trouble to find out who he was, for names were not very often given in the early days.

“He’s called Charlie Chaplin”, the manager of the cinema told us, a little surprised no doubt that one so young could be all that interested.

Comment: Verne Morgan lived in Kent, and became a writer of pantomimes and theatre sketches. Palais de Luxe cinemas were a chain, run by Electric Theatres (1908) Ltd. Jury’s Imperial Pictures was a producer and distributor, must did not manage cinemas. The period described is the early to mid-1910s: the Italian film Quo Vadis was made in 1913 and Chaplin’s first films were released in 1914. The mention of a piano player being introduced suggests that the earlier screenings had been watched without musical accompaniment.