Source: Dorothy Richardson, ‘Continuous Performance’, Close Up vol. X no. 2, June 1933, pp. 130-132

Text: One can grow rather more than weary of hearing that the Drama is on its death-bed. For although there is no need to listen to them, it is not easy to escape the voices of the prophets of woe. They sound out across the world at large, and each little world within it has private vocalists. And there is a certain grim fascination in the spectacle of their futility. What are they? What purpose, since no one heeds their warnings, can they possibly serve? Are they the lunatic fringe, the outside edge of common prudence, the fantastic exaggeration that alone seems able to command fruitful attention? But they don’t, in their own day, command fruitful attention, nor do all of them exaggerate. “Oh, Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that slayest the prophets, hadst thou but known in this thy day the things that belong unto thy peace!” Woe over tribulation that might have been averted if the prophets had been listened to. But in the little world of The Drama, the mourning prophet, true or false, gleams with a perfection of meaninglessness. If his word be false, what does it matter? If true, what can be done? For though cascades of tears may relieve the hearts of those at the bedside, they will not restore the patient.

Meanwhile Drama, variously encumbered, goes its way. And from time to time a play appears — either refreshingly of its time or, equally refreshingly, standing well back within one or other of the grand traditions — and deals with its audiences much as did, when first they dawned, the plays that now are classics, assembled in groups under period labels.

Yet still the prophets howl. And so monotonous is their note, that it is a relief to hear one howling with a difference. Lo, says this newcomer, the drama, is starved for lack of good new dramatists, but all is well with the theatre, since it can carry on with revivals. Triumph-song of an inheritor. Drama comes and drama goes, but the stage goes on for ever. Selah. No matter that one disagrees with his diagnosis. One can stand at his side and drink to the drama in general, date unspecified.

But this prophet has not done with us. Having passed sentence on The Drama, and forthwith commuted it on account of past achievements, he turns to the Film. We learn that the Cinema, like the stage, is starving for lack of good writers. Unlike the stage, it has no classics to fall back upon and must therefore starve to death. Result: the days of the Cinema are numbered.

Why, it may well be enquired, since everyone knows that there is, the world over, a sufficiency of good films to keep going for an indefinite period the cinemas run for those who prefer good films and more than a sufficiency for those who prefer other films, why tilt at such a preposterous windmill? Why not enquire, with transatlantic simplicity, “What’s biting you?” And why not politely indicate one or two recently-appeared masterpieces and point out that they could be exhibited in the world’s leading Cinemas simultaneously, whereas the stage —

Quite. But there is in this prophet’s outcry something more than a pessimism so neat and so mathematical as to have the air of a pastime not unlike a jigsaw puzzle. And while indeed it might be a pastime to oppose the statement on its own ground, in the accredited heavy-weight boxing style of the debating-society, by retorting that if the Stage can worry along on classics, so can the Cinema, by filming these classics, it may not be out of place to take a look at the unconscious assumption underlying this prophet’s neat equation. The assumption that the Cinema is merely the Stage with a difference. For this assumption is one that the general public, including ourselves, is daily more and more inclined to make. Growing talkie-minded, we increasingly regard the Film in the light of the possibilities it shares with the Stage.

For Stage and Screen, falsifying the prophecies of those who saw in the Talkies the doom of the Theatre, have become a joint-stock company, to the benefit of both parties. They, so to speak, try things out for each other. Successful plays are filmed, successful films are made into plays. Insensibly therefore, the screen’s patron, the general public including ourselves, while more or less constantly aware of the ways in which Stage outdoes Film and gets the better of Stage, is apt increasingly to regard the Film as the purveyor of Drama.

We hear of a good film. Born as a film. Or as the brilliant by-product of an obscure novel. Or as the screen equivalent of a good play. The organiser of the cinema showing this film obligingly indicates the times at which it may be seen. We look in. See our play and come away. We are play-goers.

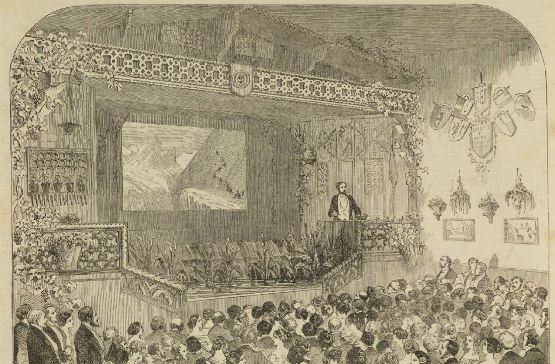

But Cinema could subsist without these events. And could make us attend to it. And even these are ultimately dependent, for their pull on us, upon the peculiar quality of the film’s continuous performance, the unchallenged achievement that so overwhelmingly stated itself when the first “Animated Pictures” cast their uncanny spell with the dim, blurred, continuously sparking representation of a locomotive advancing full steam upon the audience, majestic and terrible.

It was the first hint of the Film’s power of tackling aspects of reality that no other art can adequately handle. But the power of the Film, of Film drama, filmed realities, filmed uplift and education, all its achievements in the realm of the Good, the True and the Beautiful, appealing to the many, and in the realm of the abstract, appealing only to the few, rests alike for the uninstructed, purblind onlooker and the sophisticated kinist, upon the direct relationship, mystic, joyous, wonderful, between the observer a continuous miracle of form in movement, of light and shadow in movement, the continuous performance, going on behind all invitations to focus upon this or that, of the film itself. And if to-morrow all playwrights and all plays should disappear, the Film would still have its thousand resources while the Stage, bereft of its sole material, would die. Except, perhaps, for ballet?

Comments: Dorothy Richardson (1873-1957) was a British modernist novelist. Through 1927-1933 she wrote a column, ‘Continuous Performance’ for the film art journal Close Up. The column concentrates on film audiences rather than the films themselves. The above essay was the last in the series.

All of the ‘Continuous Performance’ essays have now been published on this site, thanks to the full set of Close Up digitised by the Media History Digital Library. This is the full list, in chronological order:

‘Continuous Performance’, Close Up vol. I no. 1, July 1927

‘Musical Accompaniment’, Close Up vol. I no. 2, August 1927

‘Captions’, Close Up vol. I no. 3, September 1927

‘A Thousand Pities’, Close Up vol. I no. 4, October 1927

‘There’s No Place Like Home’, Close Up vol. I no. 5, November 1927

‘The Increasing Congregation’, Close Up vol. I no. 6, December 1927

‘The Front Rows’, Close Up vol. II no. 1, January 1928

‘Continuous Performance VIII’, Close Up vol. II no. 3, March 1928

‘The Thoroughly Popular Film’, Close Up vol. II no. 4, April 1928

‘The Cinema in the Slums’, Close Up vol. II no. 5, May 1928

‘Slow Motion’, Close Up vol. II no. 6, June 1928

‘The Cinema in Arcady’, Close Up vol. II no. 1, July 1928

‘Pictures and Films’, Close Up vol. IV no. 1, January 1929

‘Almost Persuaded’, Close Up vol. IV no. 6, June 1929

‘Dialogue in Dixie’, Close Up vol. V no. 3, September 1929, pp. 211-218

‘A Tear for Lycidas’, Close Up vol. VII no. 3, September 1930

‘Narcissus’, Close Up vol. VIII no. 3, September 1931

‘This Spoon-fed Generation?’, Close Up vol. VIII no. 4, December 1931

‘The Film Gone Male’, Close Up vol. IX no. 1, March 1932

‘Continuous Performance’, Close Up vol. X no. 2, June 1933