Source: Dorothy Richardson, ‘Continuous Performance VI: The Increasing Congregation’, Close Up vol. I no. 6, December 1927, pp. 61-65

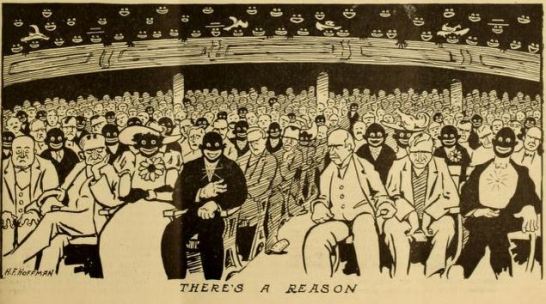

Text: It is the London season. Not a day must be lost nor any conspicuous event. And the cinema, having been first a nine months wonder and then, almost to date, a perennial perplexity, matter for public repudiation mitigated by private and, with fair good fortune, securely invisible patronage, is now part of our lives, ranks, as a topic, alongside the theatre and there are Films that must be seen. We go. No longer in secret and in taxis and alone, but openly in parties in the car. We emerge, glitter for a moment in the brilliant light of the new flamboyant foyer, and disappear for the evening into the queer faintly indecent gloom. Such illumination as there will be, moments of the familiar sense of the visible audience, of purposefully being somewhere, is but hail and farewell leaving our party again isolated amidst unknown invisible humanity. Anyone may be there. Anyone is there and everyone, and not segregated in a tier-quenched background nor packed away up under the roof. During the brief interval we behold not massed splendours bordered by a row of newspaper men, but everyone, filling the larger space, oddly ahead of us.

“What about a Movie? That one at the Excelsior sounds quite good.” Suggestions made off-hand. A Theatre is a rarity, to be selected with care, anticipated, experienced, discussed at great length, long remembered. But a film more or less is neither here nor there. May be good may be surprisingly good in the way of this strange new goodness provided for hours of relaxation and that nobody seems quite sure what to think of. It will at least be an evening’s entertainment, a welcome change from talk, reading, bridge, wireless, gramophone. And the trip down town revives the unfailing bright sense of going out, lifts off the burden and heat of the day and if the rest of the evening is a failure it is not an elaborately arranged and expensive failure.

There’s pictures going on all over London always making something to do whenever you want to go out specially those big new ones with orchestras. Splendid. It’s the next best thing to a dance and sure to be good you can get a nice meal at a restaurant and decide while you’re there and if the one you choose is full up there’s another round the corner nothing to fix up and worry about. And it’s all so nice nothing poky and those fine great entrance halls everything smart and just right and waiting there for friends you feel in society like anybody else if your hat’s all right and your things and my word the ready-mades are so cheap nowadays you need never go shabby and the commissionnaires and all those smart people about makes you feel smart. It’s as good an evening as you can have and time for a nice bit of supper afterwards.

It is Monday. Thursday. The pence for the pictures are in the jar beside the saucer of coppers for the slot metre. But folded behind the jar are unpaid bills. In the jar are threepence and six halfpence … “Me and ‘Erb tonight, then we’ll have to manage for Dad and Alf Thurdsay and then no more for a bit. … Whatever did we used to do when there was no pictures? Best we could I s’pose, and must again.”

“Never swore I wouldn’t go again this week. Never said swelp me. Might be doin’ worse. Its me own money anyway.”

“Goin’ on now. This minute. Pickshers goin’ on now. Thou shalt not ste… Goin’ on and me ‘ere. It won’t be, if I pay it back. …”

And so here we all are. All over London, all over England, all over the world. Together in this strange hospice risen overnight, rough and provisional but guerdon none the less of a world in the making. Never before was such all-embracing hospitality save in an ever-open church where kneels madame hastened in to make her duties between a visit to her dressmaker and an assignation, where the dustman’s wife bustles in with infants and market-basket.

Universal hospitality. See that starveling, lean with loathing, feeding his unknown desperate longings upon selected books, giving his approval to tortoiseshell cats. He creeps in here. Braving the herd he creeps in. His scorn for the film is not more inspiring than the fact of his presence.

And that pleasant intellectual, grown a little weary of the things of the mind, his stock-in-trade. He comes not for ideas, but to cease in his mild circling, to use the cinema as a stupifier, forty winks for his cherished intelligence. He will go away refreshed to write his next article.

Happy youth, happy childhood, weary women of all classes for whom at home there is no resting-place. Sensitives creep in here to sit clothed in merciful darkness. See those elders in whose ears sound always the approaching footsteps of death. Here, now and again, they are free from the sense of moments ticked off. See the beatitude of the stone-deaf. And that charming girl lost, despairing in the midst of her first quarrel who would no more go to an entertainment alone than she would disrobe herself in the street. But this refuge near her lodgings opens its twilit spaces and makes itself her weepery.

Refuge, trysting-place, village pump, stimulant, shelter from rain and cold at less than the price of an evening’s light and fire, drunkenness at less than the price of a drink. Instruction. Peeps behind scenes. Sermons. Homethrusts for hims and for hers, impartially.

School, salon, brothel, bethel, newspaper, art science, religion, philosophy, commerce, sport, adventure; flashes of beauty of all sorts. The only anything and everything. And here we all are, as never before. What will it do with us?

Comments: Dorothy Richardson (1873-1957) was a British modernist novelist. Through 1927-1933 she wrote a column, ‘Continuous Performance’ for the film art journal Close Up. The column concentrates on film audiences rather than the films themselves.

Links: Copy at Internet Archive