Source: John Dos Passos, Three Soldiers (New York: George Doran Company, 1920), pp. 25-27

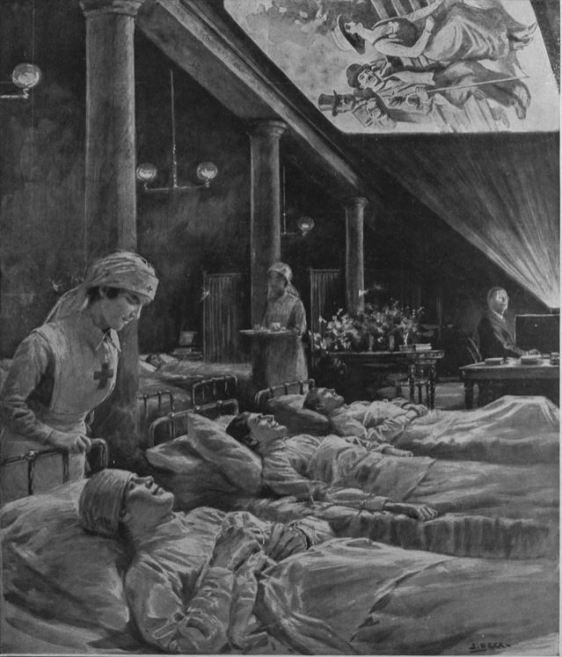

Text: “Now, fellows, all together,” cried the “Y” man who stood with his arms stretched wide in front of the movie screen. The piano started jingling and the roomful of crowded soldiers roared out:

“Hail, Hail, the gang’s all here;

We’re going to get the Kaiser,

We’re going to get the Kaiser,

We’re going to get the Kaiser,

Now!”

The rafters rang with their deep voices.

The “Y” man twisted his lean face into a facetious expression.

“Somebody tried to put one over on the ‘Y’ man and sing ‘What the hell do we care?’ But you do care, don’t you, Buddy?” he shouted.

There was a little rattle of laughter.

“Now, once more,” said the “Y” man again, “and lots of guts in the get and lots of kill in the Kaiser. Now all together. … ”

The moving pictures had begun. John Andrews looked furtively about him, at the face of the Indiana boy beside him intent on the screen, at the tanned faces and the close-cropped heads that rose above the mass of khaki-covered bodies about him. Here and there a pair of eyes glinted in the white flickering light from the screen. Waves of laughter or of little exclamations passed over them. They were all so alike, they seemed at moments to be but one organism. This was what he had sought when he had enlisted, he said to himself. It was in this that he would take refuge from the horror of the world that had fallen upon him. He was sick of revolt, of thought, of carrying his individuality like a banner above the turmoil. This was much better, to let everything go, to stamp out his maddening desire for music, to humble himself into the mud of common slavery. He was still tingling with sudden anger from the officer’s voice that morning: “Sergeant, who is this man?” The officer had stared in his face, as a man might stare at a piece of furniture.

“Ain’t this some film?” Chrisfield turned to him with a smile that drove his anger away in a pleasant feeling of comradeship.

“The part that’s comin’s fine. I seen it before out in Frisco,” said the man on the other side of Andrews. “Gee, it makes ye hate the Huns.”

The man at the piano jingled elaborately in the intermission between the two parts of the movie.

The Indiana boy leaned in front of John Andrews, putting an arm round his shoulders, and talked to the other man.

“You from Frisco?”

“Yare.”

“That’s goddam funny. You’re from the Coast, this feller’s from New York, an’ Ah’m from ole Indiana, right in the middle.”

“What company you in?”

“Ah ain’t yet. This feller an me’s in Casuals.”

“That’s a hell of a place. … Say, my name’s Fuselli.”

“Mahn’s Chrisfield.”

“Mine’s Andrews.”

“How soon’s it take a feller to git out o’ this camp?”

“Dunno. Some guys says three weeks and some says six months. … Say, mebbe you’ll get into our company. They transferred a lot of men out the other day, an’ the corporal says they’re going to give us rookies instead.”

“Goddam it, though, but Ah want to git overseas.”

“It’s swell over there,” said Fuselli, “everything’s awful pretty-like. Picturesque, they call it. And the people wears peasant costumes. … I had an uncle who used to tell me about it. He came from near Torino.”

“Where’s that?”

“I dunno. He’s an Eyetalian.”

“Say, how long does it take to git overseas?”

“Oh, a week or two,” said Andrews.

“As long as that?” But the movie had begun again, unfolding scenes of soldiers in spiked helmets marching into Belgian cities full of little milk carts drawn by dogs and old women in peasant costume. There were hisses and catcalls when a German flag was seen, and as the troops were pictured advancing, bayonetting the civilians in wide Dutch pants, the old women with starched caps, the soldiers packed into the stuffy Y.M.C.A. hut shouted oaths at them. Andrews felt blind hatred stirring like something that had a life of its own in the young men about him. He was lost in it, carried away in it, as in a stampede of wild cattle. The terror of it was like ferocious hands clutching his throat. He glanced at the faces round him. They were all intent and flushed, glinting with sweat in the heat of the room.

As he was leaving the hut, pressed in a tight stream of soldiers moving towards the door, Andrews heard a man say:

“I never raped a woman in my life, but by God, I’m going to. I’d give a lot to rape some of those goddam German women.”

“I hate ’em too,” came another voice, “men, women, children and unborn children. They’re either jackasses or full of the lust for power like their rulers are, to let themselves be governed by a bunch of warlords like that.”

Comments: John Dos Passos (1896-1970) was an American modernist novelist. His second novel, Three Soldiers (1920) is an antiwar work which stresses the dehumanising effects of war. Dos Passos served as an ambulance driver during the First World War. The scene here takes place in an American town close to troop barracks.

Links: Copy at Internet Archive