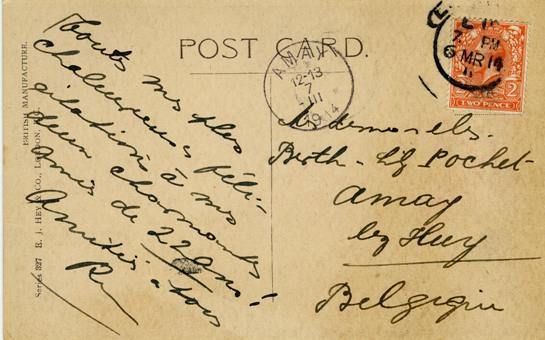

Source: Jacobus vann Looy, ‘Het verhaal van den provinciaal’ in De wonderlijke avonturen van Zebedeus, nieuwe bijlagen (Amsterdam: S.L. van Looy, 1925), pp. 149-161, originally published as ‘Nieuwe bijlagen. XXV’, in De Nieuwe Gids (1917) pp. 361-376

Text: In het Phebus-theater,

Waar anders geen geschater

Van luiten heerscht, maar nu een gróot orchest

Spelende was en tevens voor het lest,

Naar ik las in een advertentie,

In een blad uit de residentie,

Provinciale, wel te verstaan,

Ofschoon het mij er heen toch heeft doen gaan,

En alhoewel ik heimelijk bleef hopen

Dat het niet zoo’n vaart zou loopen,

Dat het niet zou zijn als wat

Ik er over gelezen had…

Ik ging om kort te gaan door ‘t drukke avondlicht,

Als of ik ging naar een gewijd gesticht;

En vroeg ter plaatse naar een plaats, een bèste…

‘U komt toch zeker niet om het orchest, è?’

Vroeg mij een gemobiliseerde man;

‘Achter-an,

Het beste is ook het duurste, zult u weten.’

Hij deed een dame glimlachen daar, gezeten

In een soort van tempeltje,

Voor een poortje als een vlieggat met een drempeltje,

Als eene duive, in kraagdons, ja,

Van Venus of van Diana,

Al zat zij er gelijk een fotografiste

In ‘t rooie kamertje en bleek te zijn de caissiste,

En jong genoeg nog om de favouriete

Van een roman te zijn, zelfs nog zonder…

Evenmin als Diana, ‘t woord behelst geen schand’,

Is aan het Fransch ‘têter’ verwant,…

Tout homme a deux pays, le sien et puis la France,

Spreekt ook Englands dichter niet van popkens laten dansen?

Bestaat iets lievers dan wanneer van honger en van dorst,

Zoo’n heel klein menschje nog klokt aan de moederborst?…

Gewis, zij lachte, wis…

‘k Begrijp niet goed wat steeds aan mij te lachen is;

Zooals van ochtend ook de Directeur

Der Hulpbank deed, toen ‘k mij vergist had in de deur,

En heel ‘t lokaal met zijn persoon vervulde,

Een mensch is meer toch dan ‘n bankje van duizend gulden…

Al moog’ geen ridderorde mij de borst bepralen,

En had ik nooit ‘t geluk om mijne graad te halen,

Een ieder heeft zijn weet,

Lachen is wreed.

‘Smaadt de materie niet,’ als laatst de poldergast zei,

Toen hij zijn hand op ‘t zware heiblok lei;

‘Ik wil wel graag een praatje met u maken,

Maar smaadt mij niet de materie, ze kan je zoo leelijk kraken.

In het Phebus-theater,

Als in een grot onder water,

Als in een school of in de kerk

Van een ondergrondsch loopgravenwerk,

In eene pijpenlade

Waar ieder vrij mocht rooken zonder schade,

Zat ik dan

In afwachting van…

Er gloeiden lampen,

Lantarentjes, tegen rampen,

Er was een radertje, ik hoor nog hoe het snort,

En over mij zag ik een blind-wit bord;

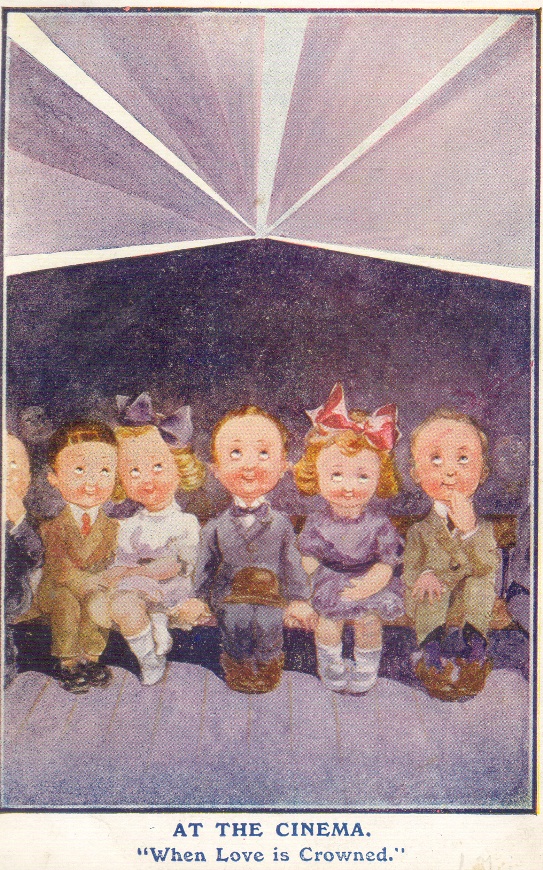

Er zaten andren reeds, die hun gezicht toekeerden;

Allen gemobiliseerden,

Allen mij onbekenden,

Gelukkig niet een mij kende;

Er kwamen er nog meer,

Naast mij zeeg een juffrouw op het stoeltje neêr…

Een paartje volgde, een moeder en een zoon;

Van welk geslacht dan ook, ‘t geldt altijd een persoon;

Een heer zei overluid: ‘hij wou bij de kachel zitten,’

Al meer en meerder kwamen samenklitten,

Om zoo te zeggen, in dit hol,

En aldus werd het Phebus-theater zienderoogen vol.

En toen, nog stom,

Triangel kwam, horen schreed aan en trom,

Allen gemobiliseerden,

Een vedel dan een weinig soupireerde,

Want die het hoogste zat, vóor de piano, was

Dezelfde Diana van zoo pas.

Maar de klavierlamp nu ontstak

Haar roode tunica, haar bloese of haar jak.

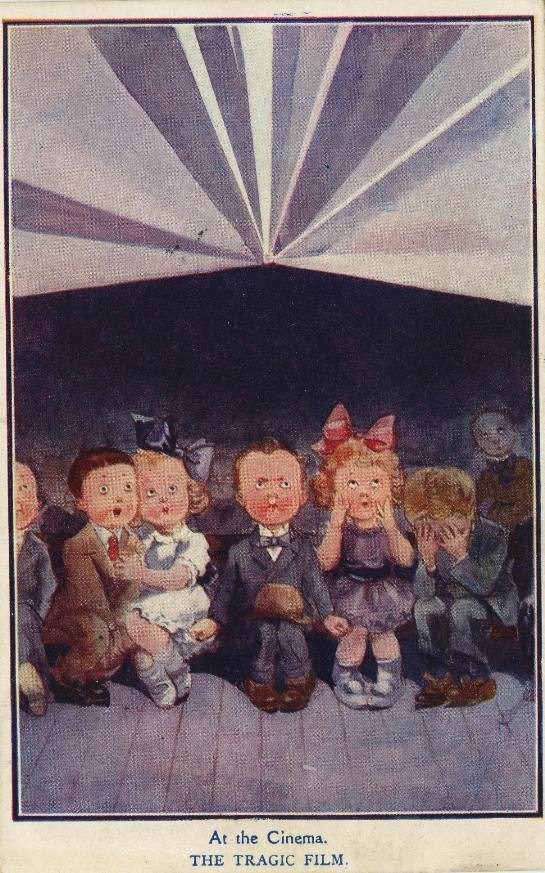

Eensklaps werd het donker.

De lampjes smeulden als door kolengasgeflonker

En heel de ruimt’ verkeerde tot een klonterig gewemel

Onder den zolderhemel,

En op ‘t bord

Kwam een nattig maanlicht aangestort.

En toen, als eens voor koning Belsasar, verscheen

Schrift en weder verdween

En duister en bevlekt,

Ik zag het bord met schaduwspel bedekt.

Ik kan niet alles ordelijk vertellen,

De tafereelen bleven naar elkaâr toe snellen,

Er schoven landen

Van de een naar de andere rande,

Geheuvelde oorden,

Rivieren glommen tusschen lage boorden,

Ik kon niet immer goed zien wat het was,

Doch altijd wuivelde er wel ergens gras…

Het bord te schrikken leek; het bliksemde er en schudde,

Kolonne-lange kudden

Gemobiliseerden marcheerden door het ruim,

Zonder glorie of pluim

En zonder marketensters,

Zonder te blikken naar vensters,

Ze beenden fel

En groeiden snel…

Ik zag hun hurken gaan en eten gaan uit blikken,

Ik zag de bajonets op de geweren prikken…

Er kwamen telkens woorden op het bord,

In spiegelschrift en dikwijls schoot de laatste zin te kort,

Het leek bijwijlen een gecensureerde brief;

En aldus zag ik al de voorbereidselen van het groote offensief

Aan de Somme…

Al heviger ze roerden de tromme,

De piano, de fluit, de horen,

Het daverde in mijn ooren,

Ze ontwikkelden minder leven nauw

Dan het orchest in het Concert-gebouw;

‘t Geweld ter tonen maakte mij benepen…

‘Maar u hebt nooit van Wagner veel begrepen,

Hij brengt u van de wijs,’

Zooals mevrouw van M… mij zeide te Parijs…

In Parijs, o, toen Wagner daar was en vogue,

En ik bekende dat mijn hart meer naar Beethoven trok,

De negende simfonie…

Eensklaps voelde ik mijn buurvrouws knie,

Zoo beenen zenuwachtig worden voor ze dansen gaan,

Wroetelen tegen de mijne aan,

En weder raasde ‘t leven om mij om

Van de stalen driehoek, ‘t koper en de trom

En van het heet-bestreken snaar-instrument,

Maar toch, die pianiste had beslist talent…

Een heele poos leek alles mij te ontwijken,

Toen zag ik ammunitie als mij aan staan kijken,

Ontzaggelijk en vreemde…

‘De kneuzende oorlogsvracht beploegde Vlaandrens beemden’

Ging mij door het brein, ziende het vervoer,

De logge leger-auto’s horten langs den vloer.

Ik zag de kogels uitgespreid en opgesteld,

Zooals gerooide rapen liggen op het veld;

Ontelbaar, her en der, tot in het ver verschiet,

Als wat in ‘n lang gevoelde behoefte eindelijk voorziet.

Ik zag ze staan en zonder blussen, deuken,

En heb gedacht aan beuken,

Niet aan het werkwoord van dien naam natuurlijk,

In eenen zin figuurlijk,

Die vrouwelijkste boomen in het bosch,

Zoo blank ze waren, elegant en los,

Gebonden en gevlerkt,

Geen damesnagels fijner afgewerkt;

Ik zag ze daar verpakt als flesschen wijn,

In mandjes als om teêre vruchten zijn;

Soms kerkbeeld-hoog en als een spitsboograam,

En vele droegen ‘n naam,

Een naam als bakers voor de kinderen bedenken…

Een Tommie lag er languit bovenop te wenken,

Hij streelde met zijn handen zulk een pracht-granaat;

En nooit zal ik vergeten zijn gelaat,

Het vroolijke, dat mijlen van mij was,

En sneeuwwit was.

Bom! bom!

Kanonnen sjorden aan en stonden stom,

Als steigerende rossen in hun stalen toomen,

Onder het loof van boomen;

Kolossaal,

Als één stuk zwart metaal;

Machines als nog nooit een industrie gebruikte,

Ze nergens stuikten,

Na goed te zijn gesmeerd.

Het leek wel of zij ‘t hadden uit hun hoofd geleerd…

Ik zag het projectiel erin gedreven,

‘Many happy returns,’ met krijt er op geschreven,

En toen ze schoten zag ik dunne smook,

En schimmen loopen gaan die leken rook,

Voorover, met de vingers in hun ooren…

Hoe vreemd het is daar niet iets van te hooren…

Dan kreeg de dikke loop vanzelf een schok

En gliste weêr terug alsof er een aan trok,

Zoo zoetjes-an,

Si doucement.

En toen verscheen een randje gras met draad behekt,

Een lucht er boven was met wolkjes bedekt,

Het leek een droomerige aquarel,

Van Mauve of Israëls…

Dat al die mooie dingen gaan zoo duur…

Er ijlden door het bord stralen en spetten vuur;

‘t Verbeeldde ‘de overkant’.

En duidelijk was er brand,

Ik kan niet alles melden zoo ik wou,

Het ging zoo gauw.

Ik heb ook mijnen uit elkaâr zien slaan,

Fonteinen modder, als een inkt-vulkaan,

Of bergen sintels werden opgeblazen

Van al de boeken, schriften waar wij over lazen;

En daarna was

Weêr alles grijs als asch.

En hangend aan de gordels van soldaten,

Zag ik de handgranaten,

En in een schans en op een planken vloer,

Aan balen zand geleund, een schim staan op de loer,

Zijn helm blonk bovenuit den rand der terp,

Leek een historisch kunstvoorwerp,

Een omgekeerde kop of een bokaal

Waaruit gedronken werd bij ‘t schimmenmaal,

In het Walhalla,

Der in den krijg gevallen,

Verslagen reuzen,

En dienend om de hersens niet te kneuzen…

Een paard met bollen buik, geloof ik, ik dan zag,

Het was het vierde of het vijfde dat er reed of lag,

En naar twee hondjes heb ik ook gestaard,

Ze tripten naast een fuselier of naast een Gordon-guard.

En in een hut die leek van sneeuw gebouwd,

Werd, meen ik, door Lancasters met ‘n katapult gesjouwd;

Ik zag een bom hen stellen en ze duiken snel,

En weg hij was als de appel van Willem Tell;

Een ‘liebesgabe’ naar het bord vermeldde…

Mortieren zag ik klaar of gaan te velde,

Mitrailleuses, ik weet niet wat het was,

Maar altijd wuivelde er wel ergens gras…

Plots hel het werd;

Ik heb mijn blikken in de zaal toen opgesperd,

Het leek mij of zij waren ingekort,

Of alle menschen zeulden naar het bleeke bord.

Het zien van kleuren schonk wat leniging,

Het was of allen waren in versteeniging,

Een moeder raakte aan den arm haars zoons, bij ongeval,

En dat was al.

De juffrouw zag mij aan… het werd al weder donker,

En boven het geflonker

Der roode jaagster aan de piano,

En boven al de kruinen der gemobiliseerden, o,

Grimde naar het duister van de hal:

‘De aanval.’

En de jacht

Van de gelijke schimmen reed weêr door den nacht,

Ze spookten op het roeren onzer trom,

Bom-bom, bom-bom!

Uit hoeken en gaten,

Met glad-geschoren gelaten,

Door rattengangen, een voor een,

Verdekt ze slopen door de maan die scheen,

Naar de verzamelplaatse, zoo

De varkens in fabrieken gaan te Chicago:

‘k Hoorde in de verte: ‘Tipperary!’

Joelen uit veel bombarie,

En zag ze samen in paradedos,

Ze maakten hier wat vast, ze maakten daar wat los,

Er was er eentje bij

Die groette mij.

Ik zag hen in gelederen en rijen,

Gegroept, gescheien,

En voor een priester op de knie gevallen,

Ik zag de geultjes in hun halzen alle;

De evangeliedienaar had een wit hemd aan,

Zoo blank en zuiver als de volle maan;

En ‘k zag hen uit hun korrelige slooten springen,

En over gruis en stronken voorwaarts dringen,

Er viel er een neêr als een leêge jas,

En verder nog een waar nog woei wat gras…

Ik kon het niet ontwijken…

Ik was gekomen hier toch om te kijken…

Het was voorbij…

Plots spraken er twee heeren achter mij,

De een zei: ‘t was kemedie, dat ‘t hem tegenviel,

Dat ‘t hem tegenviel,

En de andre hooren deed:

‘Och, alle waar is naar zijn geld, je weet.’

Ik keek niet om en heb me stijf gehouden,

Uit vreeze dat zij mij misschien herkennen zouden;

Doch weder was er de aandacht uit mij henen…

Een overwonnen krater was op ‘t bord verschenen,

Eén stond er midden in, hij ging er gansch in schuil,

Gelijk een mierenleeuw, verzonken in zijn kuil.

Ik had door al die tusschenwerpsels wat gemist,

Vast en beslist,

Er woei niet langer gras,

De gronden leken van verbrijzeld glas,

Of rullige akkers vol geschilde rapen;

Er doolden een paar schimmen om van knapen,

Padvinders, zoekende herinneringen op…

En ‘k zag een open hut aan de uitgang van een slop,

Een tunnel, en de vedel was gaan klagen…

Ze droegen zwarte staven aan waarop gestalten lagen;

De ruimte van het bord

Was veel te kort.

De dragers met de kruisen op hun mouw,

Aanbukten reuzengroot en blinkend weg in ‘t nauw,

Lieten de baren blijven.

Ik kan het niet beschrijven,

‘t Was alles afgekeerd en dichtgemaakt…

Een beeld zat in de hut tot aan zijn gordel naakt.

Zijn arm hing naar mij toe, de hand geheel beklad,

Er leek een volle inktpot over uit gespat,

Hoog op zijn bovenarm was ook ‘n donkre smet,

De witte dokter boog er naar en heeft gebet,

Gewindseld dan en met een rappen stoot,

Den mond des mans een sigaret hij bood;

De Tommie keek zijn arm langs, ademhaalde rook…

‘Hoe goed geholpen zij worden’, had ‘k gelezen ook,

Maar achter mij sprak weêr de knorge stem:

Dat ‘t tegenviel hem;

En de andre ontevreeën:

‘Dat je je geld wel beter kon besteeën.’

Wij hebben de uitgeputte krijgers ook terug zien komen,

Een wapenschouw ik zag, hen neêrgevlijd in drommen,

Hun rust genietende,

Plassend, water vergietende;

Ze wreven wapens schoon en keken soms mij aan:

‘’s Wounds, ‘t gaat daar jullie geen van allen aan.’

En op dezelfde wijs ik zag die languit lagen,

Met zware spijkerlaarzen werden aangedragen;

En ‘k heb aan gras gedacht;

Ver in het spikkelig licht ze delfden ‘n gracht;

‘Dat is een lange,’ zei mijn buurmans mond,

Toen alles op het trillend bord verzwond…

Ik wilde henengaan, doch ‘t was niet uit;

Wij kregen nog ‘de buit’.

Al de verwonnen

Kanonnen;

Allerlei zonderlinge

Geweldige keukendingen,

Ze lagen overhoop

Zoo op de Maandagmarkt de rommel ligt te koop…

En ‘k zag ‘de levende buit’,

Kluit ik zag na kluit,

Als mijnvolk uit hun schachten opgekomen;

De ontwapende, gevangen genomen

Hol-schonkige Duitschers;

Ze hieven handen, als afwerpend kluisters,

Al op en neêr in ‘t gaan,

Of trokken er touwtjes aan;

Klemden ze voor hun oogen;

In de schoeren gebogen,

Van-af de borst bedropen,

De lippen hangend open,

En met den blik aan ‘t loenen

Of wijd naar visioenen.

Ze vonden wel hun weg daar door de bermen,

De duizelende zwermen,

De spookge horden,

Versloofd, verworden,

Zonder vertoon van militair

En zonder eenig air;

Knie-knikkende,

Schimmen van schaterlachers, hikkende,

Met schel-witte verbanden

Om het gemillimeterd brein en dikwijls om hun handen;

Er stapte er een op één been,

Omhelzend twee gezwachtelden, hij hinkte heen.

Ik kon het schier niet zien, het struntelen en douwen…

Van die ‘feldgrauen’,

Het deinzen en het dollen,

Ze leken van het witte bord te rollen;

Ik zag er een stooten, bij ongeluk,

Tegen een reine Tommie, met een ruk,

Schokte zijn lijf opzij, hij blikte net

Of hij de punt gevoeld had van een bajonet…

Er schoten telkens schichten

Den warrel door der wiebelende gezichten:

De vuurge scheuten in het bord,

Als met tranen overstort.

Tranen van Tommies en grauwen,

Tranen van mannen en vrouwen,

Tranen van bruiden, moeders,

Tranen van weezen, voeders,

Van hongerige armen,

En tranen van erbarmen…

Ik heb mij goed gehouden,

Geveinsd, dat niemand iets bespeuren zoude…

Er waren witte wolkjes komen zweven,

Als die der ‘plumpuddings’ en andere granaten zooeven.

Ze boden sigaretten, hadden zich verzoend;

En toen was ‘t bord weêr blank, als plotseling afgeboend.

De zaal ontsteeg gerucht…

Ik voelde me opgelucht…

De damp van de sigaren

Verzweefde naar het licht der tooverlantaren,

Een ellenlange pluim

Die kringelblauwend schuin schoof door het ruim.

En ‘k heb gewacht…

En heb gedacht…

Het raadje snorde steeds zijn maniakke wijs,

En schoon het warm was, was ik koud als ijs…

Schimmen van stokken, stronken,

Van kluiten, brokken, bonken,

Ze bleven op het bord als aan een keten gaan,

Gelijk een menschenledig landschap op de maan…

De maan blonk aan de lucht, hoog boven alles uit,

De straat in donker door ‘t gemeenteraad-besluit,

Van lichtbesparing om de groote kolennood,

Deed me weldadig aan, het stemde me, ik genoot

Door die afwezigheid van overdaad en tinkels,

En ‘t aangegaapt te zijn door opgeschoten kinkels.

Het was nog steeds in mij, alsof in mij wat sliep,

Alsof ik binnen in een levend wezen liep,

En zag de donker-gloênde wandlaars gaan en komen,

Zooals in aderen de bloed-lichaampjes stroomen;

Het was nog steeds in mij of ik niet wakker was,

Of wat ‘k gezien het leven, dit een droom slechts was;

De toren in de diepten van den manehemel stak,

En stille, zachte waden dekten huis en dak,

En in de heimelijke schemering der straat,

De lijven bleven gaan met hun befloersd gelaat.

Tot eindelijk weder sprak in mij herinnering,

Het snorren van een raadje uit mij zelf ontging;

En ‘k langs de toeë winkels loopend verder trad,

Al mijmerzieker door de vreemde stilt’ der stad.

Ik voelde rond mij om de warmte weêr als weelde,

En overdacht de waarde dezer oorlogsbeelden,

Wat ‘k had gelezen in verslagen eener krant,

Om waar- en eerlijkheid, verheldering van verstand,

Het algemeen, groot nut van deze levende platen,

Omdat zij niets aan de verbeelding overlaten.

Ik dacht aan België, dat voor de Vrijheid vecht,

Aan nooit te delgen schuld van het geschonden Recht,

En werd al wandeldenkende weêr welgemoed,

Wijl ‘t bij ons Vreê nog is, tot dusver, alles goed.

Doch in den nacht daarop ik droomde droef,

Dat ‘k eigenhandig in een tuin een mensch begroef,

Tusschen het wuivelende gras,

En ik was

Die doode zelf;

Hij lag te staren naar het luchtgewelf

Met rond verwijde oogen:

En door den hooge

Het snorde rusteloos en heeft gewaaid,

Of werd een eindelooze film afgedraaid:

Van Donau’s, Marne’s, Aisne’s en van Yzers,

Van diplomaten, en magnaten en van keizers…

En die begroef mij deed het smart noch pijn…

Ongeloofelijke menschen wij zijn.

Comments: Jacobus van Looy (1855-1930) was a Dutch painter and writer. His 1916 poem ”Het verhaal van den provinciaal’ (‘The tale of the provincial’) tells of a man visiting a city and going to the cinema, whose conflicted views on the war and being in a cinema are revealed through the long poem’s stream of consciousness style. It is only gradually made apparent that it is the British documentary film The Battle of the Somme that he is watching. Geert Bulens (see link below) provides an analysis of poem’s themes. Practical elements referred to include projection, intertitles, and the accompanying music. Van Looy lived in Haarlem, but no cinema named Phebus-Theater is listed on the historical database of Dutch cinema, Cinema Context, in Haarlem or elsewhere. The Netherlands was neutral during the First World War. I can find no full English translation of the poem, but the penultimate stanza was translated (by Klaas de Zwaan) for my silent film blog, The Bioscope, as follows:

I felt the comforting warmth surrounding me again,

And thought over the value of these images of war,

What I’ve read in the reports of some newspapers,

About truth and honesty, clarification of the mind,

The overall, great usefulness of these living pictures,

Because they leave nothing to the imagination.

I thought of Belgium, fighting for Freedom,

An irredeemable infringement of Justice,

And while walking I pleasantly realized

Peace was among us, so far so good.

Links: Dutch text in copy of De wonderlijke avonturen van Zebedeus in DBNL (Digital Library for Dutch Literature)

Geert Buelens, ‘Sound and Realism in British and Dutch Poems Mediating The Battle of the Somme’, Journal of Dutch Literature, vol. 1 no. 1, December 2010 (includes discussion of the poem, in English)