Source: Joseph Medill Patterson, ‘The Nickelodeons: The Poor Man’s Elementary Course in the Drama’ The Saturday Evening Post, 23 November 1907, pp. 10-11, 38.

Text: Three years ago there was not a nickelodeon, or, five-cent theatre devoted to moving-picture shows, in America. To-day there are between four and five thousand running and solvent, and the number is still increasing rapidly. This is the boom time in the moving-picture business. Everybody is making money- manufacturers, renters, jobbers, exhibitors. Overproduction looms up as a certainty of the near future; but now, as one press-agent said enthusiastically, “this line is a Klondike.”

The nickelodeon in tapping an entirely new stratum of people, is developing into theatregoers a section of population that formerly knew and cared little about the drama as a fact in life. That is why “this line is a Klondike” just at present.

Incredible as it may seem, over two million people on the average attend the nickelodeons every day of the year, and a third of these are children.

Let us prove up this estimate. The agent for the biggest firm of film renters in the country told me that the average expense of running a nickelodeon was from $175 to $200 a week, divided as follows:

Wage of manager $25

Wage of Operator 20

Wage of doorman 15

Wage of porter or musician 12

Rent of film (two reels changed twice a week) 50

Rent of projecting machine 10

Rent of building 40

Music, printing, “campaign contributions,” etc. 18

Total $190

Merely to meet expenses then, the average nickelodeon must have a weekly attendance of 4000. This gives all the nickelodeons 16,000,000 a week, or over 2,000,000 a day. Two million people a day are needed before profits can begin, and the two million are forthcoming. It is a big thing, this new enterprise.

The nickelodeon is usually a tiny theatre, containing 199 seats, giving from twelve to eighteen performances a day, seven days a week. Its walls are painted red. The seats are ordinary kitchen chairs, not fastened. The only break in the red color scheme is made by half a dozen signs, in black and white, NO SMOKING, HATS OFF and sometimes, but not always, STAY AS LONG AS YOU LIKE.

The nickelodeon is usually a tiny theatre, containing 199 seats, giving from twelve to eighteen performances a day, seven days a week. Its walls are painted red. The seats are ordinary kitchen chairs, not fastened. The only break in the red color scheme is made by half a dozen signs, in black and white, NO SMOKING, HATS OFF and sometimes, but not always, STAY AS LONG AS YOU LIKE.

The spectatorium is one story high, twenty-five feet wide and about seventy feet deep. Last year or the year before it was probably a second-hand clothiers, a pawnshop or cigar store. Now, the counter has been ripped out, there is a ticket-seller’s booth where the show-window was, an automatic musical barker somewhere up in the air thunders its noise down on the passersby, and the little store has been converted into a theatrelet. Not a theatre, mind you, for theatres must take out theatrical licenses at $500 a year. Theatres seat two hundred or more people. Nickelodeons seat 199, and take out amusement licenses. This is the general rule.

But sometimes nickelodeon proprietors in favorable locations take out theatrical licenses and put in 800 or 1000 seats. In Philadelphia, there is, perhaps, the largest nickelodeon in America. It is said to pay not only the theatrical license, but also $30,000 a year ground rent and a handsome profit.

To-day there is cutthroat competition between the little nickelodeon owners, and they are beginning to compete each other out of existence. Already consolidation has set in. Film-renting firms are quietly beginning to pick up, here and there, a few nickelodeons of their own; presumably they will make better rates and give prompter service to their own theatrelets than to those belonging to outsiders. The tendency is early toward fewer, bigger, cleaner five-cent theatres and more expensive shows. Hard as this may be on the little showman who is forced out, it is good for the public, who will, in consequence, get more for their money.

Who the Patrons Are

The character of the attendance varies with the locality, but, whatever the locality, children make up about thirty-three per cent. of the crowds. For some reason, young women from sixteen to thirty years old are rarely in evidence, but many middle-aged and old women are steady patrons, who never, when a new film is to be shown, miss the opening.

In cosmopolitan city districts the foreigners attend in larger proportion than the English speakers. This is doubtless because the foreigners, shut out as they are by their alien tongues from much of the life about them can yet perfectly understand the pantomime of the moving pictures.

In cosmopolitan city districts the foreigners attend in larger proportion than the English speakers. This is doubtless because the foreigners, shut out as they are by their alien tongues from much of the life about them can yet perfectly understand the pantomime of the moving pictures.

As might be expected, the Latin races patronize the shows more consistently than Jews, Irish or Americans. Sailors of all races are devotees.

Most of the shows have musical accompaniments. The enterprising manager usually engages a human pianist with instructions to play Eliza-crossing-the-ice when the scene is shuddery, and fast ragtime in a comic kid chase. Where there is little competition, however, the manager merely presses the button and starts the automatic going, which is as apt as not to bellow out, I’d Rather Two-Step Than Waltz, Bill, just as the angel rises from the brave little hero-cripple’s corpse.

The moving pictures were used as chasers in vaudeville houses for several years before the advent of the nickelodeon. The cinemetograph or vitagraph or biograph or kinetoscope (there are seventy-odd names for the same machine) was invented in 1888-1889. Mr. Edison is said to have contributed most toward it, though several other inventors claim part of the credit.

The first very successful pictures were those of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons fight at Carson City, Nevada, in 1897. These films were shown all over the country to immense crowds and an enormous sum of money was made by the exhibitors.

The Jeffries-Sharkey fight of twenty-five rounds at Coney Island, in November, 1899, was another popular success. The contest being at night, artificial light was necessary, and 500 arc lamps were placed above the ring. Four cameras were used. While one was snapping the fighters, a second was being focused at them, a third was being reloaded, and a fourth was held in reserve in case of breakdown. Over seven miles of film were exposed, and 198,000 pictures, each 2 by 3 inches, were taken. This fight was taken at the rate of thirty pictures to the second.

The 500 arc lamps above the ring generated a temperature of about 115 degrees for the gladiators to fight in. When the event was concluded, Mr. Jeffries was overheard to remark that for no amount of money would he ever again in his life fight in such heat, pictures or no pictures. And he never has.

Since that mighty fight, manufacturers have learned a good deal about cheapening their process. Pictures instead of being 2 by 3 inches are now 5/8 by 1 1/8 inches, and are taken sixteen instead of thirty to the second, for the illusion to the eye of continuous motion is as perfect at one rate as the other.

By means of a ratchet each separate picture is made to pause a twentieth of a second before the magic-lantern lens, throwing an enlargement to life size upon the screen. Then, while the revolving shutter obscures the lens, one picture is dropped and another substituted, to make in turn its twentieth of a second display.

The films are, as a rule, exhibited at the rate at which they are taken, though chase scenes are usually thrown faster, and horse races, fire-engines and hot-moving automobiles slower, than the life-speed.

How the Drama Is Made

Within the past year an automatic process to color films has been discovered by a French firm. The pigments are applied by means of a four-color machine stencil. Beyond this bare fact the process remains a secret of the inventors. The stencil must do its work with extraordinary accuracy, for any minute error in the application of color to outline made upon the 5/8 by 1 1/8 inches print is magnified 200 times when thrown upon the screen by the magnifying lens. The remarkable thing about this automatic colorer is that it applies the pigment in slightly different outline to each successive print of a film 700 feet long. Colored films sell for about fifty per cent. more than black and whites. Tinted films – browns, blues, oranges, violets, greens and so forth – are made by washing, and sell at but one per cent. over the straight price.

The films are obtained in various ways. “Straight” shows, where the interest depends on the dramatist’s imagination and the setting, are merely playlets acted out before the rapid-fire camera. Each manufacturing firm owns a studio with property-room, dressing rooms and a completely-equipped stage. The actors are experienced professionals of just below the first rank, who are content to make from $18 to $25 a week. In France a class of moving-picture specialists has grown up who work only for the cameras, but in this country most of the artists who play in the film studios in the daytime play also behind the footlights at night.

The studio manager orders rehearsals continued until his people have their parts “face-perfect,” then he gives the word, the lens is focused, the cast works rapidly for twenty minutes while the long strip of celluloid whirs through the camera, and the performance is preserved in living, dynamic embalmment (if the phrase may be permitted) for decades to come.

Eccentric scenes, such as a chalk marking the outlines of a coat upon a piece of cloth, the scissors cutting to the lines, the needle sewing, all automatically without human help, often require a week to take. The process is ingenious. First the scissors and chalk are laid upon the edge of the cloth. The picture is taken. The camera is stopped, the scissors are moved a quarter of an inch into the cloth, the chalk is drawn a quarter of an inch over the cloth. The camera is opened again and another picture is taken showing the quarter-inch cut and quarter-inch mark. The camera is closed, another quarter inch is cut and chalked; another exposure is made. When these pictures so slowly obtained we run off rapidly, the illusion of fast self-action on the part of the scissors, chalk and needle is produced.

Sometimes in a nickelodeon you can see on the screen a building completely wrecked in five minutes. Such a film was obtained by focusing a camera at the building, and taking every salient move of the wreckers for the space, perhaps, of a fortnight. When these separate prints, obtained at varying intervals, some of them perhaps a whole day apart, are run together continuously, the appearance is of a mighty stone building being pulled to pieces like a house of blocks.

Such eccentric pictures were in high demand a couple of years ago, but now the straight-story show is running them out. The plots are improving every year in dramatic technique. Manufacturing firms pay from $5 to $25 for good stories suitable for film presentation, and it is astonishes how many sound dramatic ideas are submitted by people of insufficient education to render their thoughts into English suitable for the legitimate stage.

The moving-picture actors are becoming excellent pantomimists, which is natural, for they cannot rely on the playwright’s lines to make their meanings. I remember particularly a performance I saw near Spring Street on the Bowery, where the pantomime seemed to me in nowise inferior to that of Mademoiselle Pilar-Morin, the French pantomimist.

The nickelodeon spectators readily distinguish between good and bad acting, though they do not mark their pleasure or displeasure audibly, except very rarely, in a comedy scenes by a suppressed giggle. During the excellent show of which I have spoken, the men, woman and children maintained steady stare of fascination at the changing figures on the scene, and toward the climax, when forgiveness was cruelly denied, lips were parted and eyes filled with tears. It was as much a tribute to the actors as the loudest bravos ever shouted in the Metropolitan Opera House.

To-day a consistent plot is demanded. There must be, as in the drama, exposition, development, climax and denouement. The most popular films run from fifteen to twenty minutes and are from five hundred to eight hundred feet long. One studio manager said: “The people want a story. We run to comics generally; they seem to take best. So-and-so, however, lean more to melodrama. When we started we used to give just flashes- an engine chasing to a fire, a base-runner sliding home, a charge of cavalry. Now, for instance, if we want to work in a horse race it has to be as a scene in the life of the jockey, who is the hero of the piece – we’ve got to give them a story; they won’t take anything else – a story with plenty of action. You can’t show large conversation, you know, on the screen. More story, larger story, better story with plenty of action- that is our tendency.”

………

Civilization, all through the history of mankind, has been chiefly the property of the upper classes, but during the past century civilization has been permeating steadily downward. The leaders of this democratic movement have been general education, universal suffrage, cheap periodicals and cheap travel. To-day the moving-picture machine cannot be overlooked as an effective protagonist of democracy. For through it the drama, always a big fact in the lives of the people at the top, is now becoming a big fact in the lives of the people at the bottom. Two million of them a day have so found a new interest in life.

The prosperous Westerners, who take their week or fortnight, fall and spring, in New York, pay two dollars and a half for a seat at a problem play, a melodrama, a comedy or a show-girl show in a Broadway theatre. The stokers who have driven the Deutschland or the Lusitania from Europe pay five cents for a seat at a problem play, a melodrama, a comedy or a show-girl show in a Bowery nickelodeon. What in the difference?

The stokers, sitting on the hard, wooden chairs of the nickelodeon, experience the same emotional flux and counter-flux (more intense is their experience, for they are not as blase) as the prosperous Westerners in their red plush orchestra chairs, uptown.

The sentient life of the half-civilized beings at the bottom has been enlarged and altered, by the introduction of the dramatic motif, to resemble more closely the sentient life of the civilized beings at the top.

Take an analogous case. Is aimless travel “beneficial” or not? It is amusing, certainly; and, therefore, the aristocrats who could afford it have always traveled aimlessly. But now, says the Democratic Movement, the grand tour shall no longer be restricted to the aristocracy. Jump on the rural trolley-car, Mr. Workingman, and make a grand tour yourself. Don’t care, Mr. Workingman, whether it is “beneficial” or not. Do it because it is amusing; just as the aristocrats do.

The film makers cover the whole gamut of dramatic attractions. The extremes in the film world are as far apart as the extremes in the theatrical world- as far apart, let us say, as The Master Builder and The Gay White Way.

If you look up the moving-picture advertisements in any vaudeville trade paper you cannot help being struck with this fact. For instance, in a current number, one firm offers the following variety of attractions:

Romany’s Revenge (very dramatic) 300 feet

Johnny’s Run (comic kid chase) 300 ”

Roof to Cellar (absorbing comedy) 782 ”

Wizard’s World (fantastic comedy) 350 ”

Sailor’s Return (highly dramatic) 535 ”

A Mother’s Sin (beautiful, dramatic and moral) 392 ”

Knight Errant (old historical drama) 421 ”

Village Fire Brigade (big laugh) 325 ”

Catch the Kid (a scream) 270 ”

The Coroner’s Mistake (comic ghost story) 430 ”

Fatal Hand (dramatic) 432 “

Another firm advertises in huge type, in the trade papers:

LIFE AND PASSION OF CHRIST

Five Parts, Thirty-nine Pictures, 3114 feet Price, $373.78

Extra for coloring $125.10

The presentation by the picture machine of the Passion Play in this country was undertaken with considerable hesitation. The films had been shown in France to huge crowds, but here, so little were even professional students of American lower-class taste able to gauge it in advance, that the presenters feared the Passion Play might be boycotted, if not, indeed, indeed, in some places, mobbed. On the contrary, it has been the biggest success ever known to the business.

Last year incidents leading up to the murder of Stanford White were shown, succeeded enormously for a very few weeks, then flattened out completely and were withdrawn. Film people are as much at sea about what their crowds will like as the managers in the “legitimate.”

Although the gourdlike growth of the nickelodeon business as a factor in the conscious life of Americans is not yet appreciated, already a good many people are disturbed by what they do know of the thing.

Those who are “interested in the poor” are wondering whether the five-cent theatre is a good influence, and asking themselves gravely whether it should be encouraged or checked (with the help of the police).

Is the theatre a “good” or a “bad” influence? The adjectives don’t fit the case. Neither do they fit the case of the nickelodeon, which is merely the theatre demociatized.

Take the case of the Passion Play, for instance. Is it irreverent to portray the Passion, Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension in a vaudeville theatre over a darkened stage where half an hour before a couple of painted, short-skirted girls were doing a “sister-act”? What is the motive which draws crowds poor people to nickelodeons to see the Birth in the Manger flashed magic-lanternwise upon a white cloth? Curiosity? Mere mocking curiosity, perhaps? I cannot answer.

Neither could I say what it is that, every fifth year, draws our plutocrats to Oberammergau, where at the cost, from first to last, of thousands of dollars and days of time, they view a similar spectacle presented in a sunny Bavarian setting.

It is reasonable, however, to believe that the same feelings, whatever they are, which drew our rich to Oberammergau, draw our poor to the nickelodeons. Whether the powerful emotional reactions produced in the spectator by the Passion Play are “beneficial” or not is as far beyond decision as the question whether a man or an oyster is happier. The man is more, feels more, than the oyster. The beholder of the Passion Play is more, feels more, than the non-beholder.

Whether for weal or woe, humanity has ceaselessly striven to complicate life, to diversify and make subtle the emotions, to create and gratify the new and artificial spiritual wants, to know more and feel more both of good and evil, to attain a greater degree of self-consciousness; just as the one fundamental instinct of the youth, which most systems of education have been vainly organized to eradicate, is to find out what the man knows.

In this eternal struggle for more self-consciousness, the moving-picture machine, uncouth instrument though it be, has enlisted itself on especial behalf of the least enlightened, those who are below the reach even of the yellow journals. For although in the prosperous vaudeville houses the machine is but a toy, a “chaser,” in the nickelodeons it is the central, absorbing fact, which strengthens, widens, vivifies subjective life; which teaches living other than living through the senses alone. Already, perhaps, touching him at the psychological moment, it has awakened to his first, groping, necessary discontent the spirit of an artist of the future, who otherwise would have remained mute and motionless.

The nickelodeons are merely an extension course in civilization, teaching both its “badness” and its “goodness.” They have come in obedience to the law of supply and demand; and they will stay as long as the slums stay, for in the slums they are the fittest and must survive.

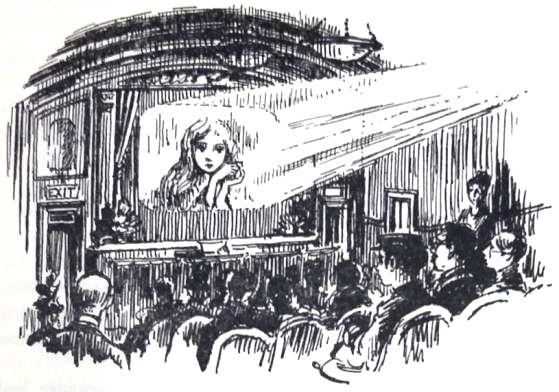

Comments: Joseph Medill Patterson (1879-1946) was an American journalist and newspaper publisher, founder of the New York Daily News. Nickelodeons (a nickname given in America to the shop-conversions that preceded purpose-built cinemas) came to the interest on general newspapers and magazines in 1907. The illustrations come from the original publication.

Links:

Copy at Hathi Trust

Transcribed copy at The Silent Bookshelf (archived site)