Source: Stephen Paget, ‘Moving Pictures’, in I Sometimes Think: Essays for the Young People (London: Macmillan, 1916), pp. 68-85

Text: We are so accustomed to moving pictures, that we do not trouble ourselves to study their nature, or their place in the general order of things. We take them for granted. Youth, especially, takes them for granted, having no memory of a time when they were not. But some of us were born into a world in which all the pictures stood still: and I challenge youth to defend the cause of moving pictures. Let the lists be set, and the signal given for the assault. On the shield of youth, the motto is Moving Pictures are All Right. On my antiquated shield, the motto is Pictures Ought Not to Move.

Pictures, of one sort or another, are of immemorial age. Portraits of the mammoth were scratched on gnawed bones, by cave-dwellers, centuries of centuries ago: and we look now at their dug-up work, and feel ourselves in touch with them. The nature of pictures was decided at the very beginning of things, as the natures of trees and of metals were decided. It is not the nature of trees to walk, nor of metals to run uphill: it is not the nature of pictures to move. Pictures and statues, by the law of their being, are forbidden to move. That commandment is laid on them which Joshua, in the Bible-story, lays on the sun and the moon–Stand thou still. They must be motionless: ’tis their nature to: they exist on that understanding, as you and I exist on the understanding that we are mortal. If I were not to die, I should not be a man. If pictures were to move, they would not be pictures.

So we come to this difficulty, that moving pictures are not pictures. We cannot evade it by giving another name to them; for it is a difficulty not of names but of natures. Let us examine it with decent care.

Moving pictures have got mankind in their enchanted net. They have unfailing power over us. Old and young, rich and poor, learned and ignorant, we are all under their spell. So magical are they, that every owner of a picture-palace would have been burned alive, not very long ago, for diabolical practices. The world is their scenery, life is their repertory, and all things in earth and air and sea are their company. They will give you, like the strolling players in Hamlet, what you desire:–

The best actors in the world, either for tragedy,

comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical,

historical-pastoral, tragical-historical,

tragical-comical-historical-pastoral, scene

individable, or poem unlimited.

Every little country-town is familiar with this vivid and precipitate entertainment. No other invention of our time–neither the electric light, nor telephones, nor aeroplanes, nor all three of them together–can show such a record of change wrought on us. Well then, what is wrong with moving pictures? Is anything wrong with them? Why should not pictures move, now that they can?

No, they must mind their own business, and do their duty in that state of life unto which it has pleased God to call them. It is not their business to move. If they were to move, the effect would be horrible: it would kill our enjoyment of them. Imagine how we should feel, if sculpture could be made to move: statues of Royalty bowing this way and that, statues of orators waving scrolls, and statues of generals waving swords: the lions in Trafalgar Square shaking their manes, and Miss Nightingale in Pall Mall raising and lowering her lamp. We should be pleased for a day or two, then bored, then disgusted. Imagine our pictures moving: the photographs on the mantelpiece, the advertisements, the big Raphael in the National Gallery.

The advertisements would matter least, because nobody cares how advertisements behave or misbehave. I have one in front of me, at this moment, from a religious journal, or a patent medicine which “creates cheerfulness by cleansing the system of its poisonous bye-products.” There is a picture of two men, one moping, the other alert. I should not like to see it move. I prefer it as it is. My imagination is free, so long as the picture is motionless; but would be hindered, if the picture moved.

The photograph of a friend, on my mantelpiece, gives play to my remembrance of him. Within the limits of photography, it is perfect. But if it moved–if its eyes followed me about the room, and its hands had that little gesture which he had with his hands, and its lips opened and shut–it would be hateful, and I should throw it in the fire.

The great pictures in the National Gallery–the Rembrandt portraits, the Raphael Madonnas–imagine them moving. Their beauty would vanish, their nature would be destroyed. The Trustees would immediately sell them, to get rid of them. Probably, they would go on tour: admission threepence, children a penny. Then they would be “filmed,” and the films would be “released,” and a hundred reproductions would be gibbering all over the country. The originals would finally be bartered, in Central Africa, to impressionable native potentates, in exchange for skins or tusks: and if pictures were able to curse, these certainly would curse the day on which they began to move.

By these instances, it is evident that pictures ought not to move. The worse they are, the less it would shock us if they did. The better they are, the more it would shock us. Why must they not move? Because they are works of art. It follows, that moving pictures are not works of art.

They are works of science: they are “scientific toys.” Science invented them, just for the fun of inventing them: made them out of an old “optical illusion.” They are that friend of my childhood, the zoëtrope, or wheel of life, adjusted to show the products of instantaneous photography. They are “applied science.” You are so familiar with them that you overlook the ingenuity of them. Here I have the advantage of you: for they came so late into my life that I was properly amazed at them. My first sight of a moving picture, like my first sight of an x-ray picture, was a revelation not to be forgotten. There was a procession of cavalry: and when I saw a photograph whisking its tail, I marvelled at a new power come into the world, and am still marvelling. But you will never get the full delight of moving pictures till you have lectured with them, been behind the scenes, handled films, and become well acquainted with those hot little fire-proof chambers where the wheels are set spinning, and the great shafts of light are projected, and out of the whirlwind of electrical forces the picture flings itself on the screen. Only, for this invention, give honour where honour is due, to Science.

But scientific inventions, unlike works of art, have an immeasurable power of growth and development. They can be improved ad libitum: they can be multiplied ad infinitum. Nothing could be less like a work of art coming from a studio than a scientific invention coming from a laboratory. The work of art is made once and for all: it may be copied, but it cannot be repeated: you cannot have two sets of Elgin Marbles, or two Sistine Madonnas. The scientific invention is like the genie who came out of the fisherman’s jar: you cannot tell where it will stop, nor what it will do next. Moving pictures may be nothing more than a scientific toy, but they are the whole world’s favourite toy: the whole world is playing with them: and if they were suddenly to be taken away, the whole world would miss them. Think what a colossal enterprise this world’s plaything now is: what legions of lives, what millions of money, are spent over the production, multiplication, and exhibition of moving pictures. Famous actors pose for them, thousands of secondary actors make a living out of them, the ends of the earth are ransacked for new scenes and subjects: even politics, and international rivalries, are dragged in the train of this huge industry. I have read of the factions which divided the people of Byzantium over their chariot-races: but these were nothing to the world’s submission to moving pictures. Is there any limit to their kingdom, any measure of their influences? These factories and companies and wholesale houses and palaces and flaming advertisements everywhere–what will be the end of it all? Thirty years hence, will they have more power over us than they have now, or less?

I hope they will have less, and will use it more carefully. I should like to see the War bring down the moving-pictures business to one-third of its present size, bring it down with a rush, and with the prospect of a further reduction. Picture-palaces in London are like public-houses: too many of them, too many of us nipping in them; too many people making money out of us, whether we be nipping in the palaces or the houses. The more we patronise them, the more they exploit us: and some of us are taking more films than are good for us. Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale? But we can easily get so fond of cakes and ale that we spoil our appetites for our regular meals. Besides, our cakes ought to be wholesome, and our ale ought not to be adulterated. The bill of fare, at the picture-palaces, includes trash: but it pays them to sell it to us: and we behave as if these palaces belonged to us, while they behave as if we belonged to them. Picture-palaces and public-houses, alike, amuse all of us and enrich some of us: they do good, they do harm: they have to be watched, these by censorship, those by the police: and both these and those are backed by wealth, and by interests too powerful to be set aside. The differences between them are accidental: the likenesses between them are essential. The moving-pictures trade is the younger of the two: and the result on us of too many films is different from the result of too much liquor. But these differences are not very profound: and the likenesses are plain enough. They would be even more plain to us, if we could have our moving pictures at home, as we have our liquor, out of a bottle. We have to go into the street for them: we have to consume them on the premises. If we could have them at home, as it were in half-pints, all to ourselves, we should more distinctly feel it our duty to draw the line at one or two, for fear of getting into a habit of them.

II

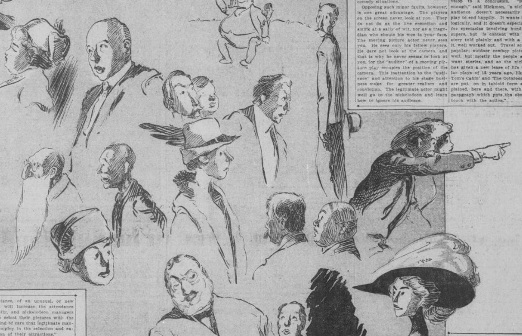

What is the nature of moving pictures? What are they “of themselves,” and where do they come in the general order of things? Take, for instance, a waterfall. If we look at a waterfall, we see water moving. If we look at a picture of a waterfall, we imagine water moving. If we look at a moving picture of a waterfall, we see a picture moving, a very beautiful object: still, we are looking at an “optical illusion,” not at a waterfall. Or take a more critical example: take a moving picture which not merely moves, but acts. What is it, really, that we are looking at, when we see, on the screen, Hamlet, or How She Rescued Him, or Charlie Chaplin? It was my privilege and honour, in the first winter of the War, to give lantern-lectures to soldiers, on the protective treatment against typhoid fever: and one happy day, we had Charlie Chaplin, till it was time to have Pasteur and the bacilli of typhoid. Besides, I have met his flat effigy, again and again, outside the palaces: that little hat and moustache, and the look of Shelley about the eyes, and that suit of clothes, and the little cane which, like General Gordon’s, is so curiously personal and inseparable from him. So I feel that I know him; and I know that I envy him: for he makes, they say, a very large income: and the laughter which he gave us that day was as clean and wholesome as the smell of a pinewood: which is more than you can say of all picture-house laughter.

But what is it, really, that I was looking at, on the screen? He is an actor equal to Dan Leno: the same unfaltering originality, the same talent for dominating the scene, holding our attention, appealing to us by his diminutive stature, his gentle acceptance of situations as he finds them, his half-unconscious air of doing unnatural things in a natural way. But think what we lose in the transition from Dan Leno on the stage to Charlie Chaplin on the screen. Dan was really there: Charlie is not. Dan talked and sang: Charlie is mute. Dan’s performance was human: Charlie’s, by the cutting of the film, and by the driving of the machine at great speed, is super-human. In brief, on the Drury Lane stage I saw Dan Leno, and heard him: but on the screen I do not see Charlie Chaplin–let alone hearing him: I see only a moving picture of him: and this picture so cleverly faked that I see him doing what he never did nor ever could. It was delightful, every moment of it: all the same, it is an optical illusion. Nor is it a straightforward illusion, like the old zoëtrope: it is rendered grotesque and fantastical by the conjuring-tricks of the people who made the film.

Still, he was delightful; for it was pantomime, dumb-show, knockabout farce, with a touch of magic in it. But I could not bring myself to see Macbeth or Hamlet on the screen; for I have seen Irving’s Macbeth and Forbes-Robertson’s Hamlet, heard their voices, learned my Shakespeare from them. Shakespeare without the words, Shakespeare without the living presence of the actor, would be intolerable. You can see, or lately could, at the “Old Vic” in the Waterloo Bridge Road, for threepence, Shakespeare acted, nobly acted, with simplicity and with dignity. Let nothing ever induce you to see him “filmed.”

Of the rest of the legion of filmed plays, let him write who can. The output of the London picture-palaces, in farce, comedy, drama, and melodrama, can hardly be less than two thousand plays twice in every twenty-four hours. Many of them are American: and those that I have seen were condensed, pungent, over-acted, and spun too fast. Now and again, a book is filmed as a play: for example, East Lynne, and Les Misérables. The effect of a filmed book might be very good: for you might get a pleasant sense that you were reading it with moving illustrations. The ordinary theatrical films cannot give you this sense. They are surprisingly clever. Only, the better they are, the more you want to have the real thing: to hear the voices, to see the players themselves. You cannot be properly thrilled by the best of heroines tied to a stake, nor by the worst of villains with a revolver: she is shrieking at the top of her voice–look at the size of her mouth–but where is the shriek? He fires–look at the smoke–but where is the bang? You are mildly excited: but you are not so excited as you ought to be: you know, all the time, that you are not at the play: you are at an optical illusion, looking with more or less interest at a scientific toy.

Give me leave to hammer at this point: for I want to make it clear to you and to myself. First, let us be agreed that a play on the stage is worth a thousand plays on the screen: for it is the real thing: it is real voices, living presences: the interpreters are there, as real as real can be. The artifices and conventions of play-acting do not spoil the reality of the play: it is only unimaginative minds which are baulked by them. A good play, well acted, satisfies and educates something in us which nothing else can reach. Call it the imagination, or the emotions, or whatever you like: the love of a good play is too old and too natural to care what name you give to it. A play on the screen is not real: there are neither voices, nor presences: there is only a moving picture, moving too swiftly to be a good picture of a play. You cannot command, over an optical illusion, the imagination and the emotions which come of themselves over a real play. They refuse to be fooled. Wrong number, they say, and put the receiver back on the hook.

It follows, that the best plays, on the screen, are those which can best afford to lose the advantage of voices and presences, and to be taken for what they are. Wild farce, with lots of conjuring-tricks in it, is the best of all. In pantomime, with a film so faked and speeded-up that fat men run a mile a minute, and cars whirl through space like shooting stars, and all Nature is convulsed, these picture-plays are at their best, joyfully turning the universe upside-down with the flick of a wheel. In the mad rush of impossibilities, there is no time for words, and no need of them. When Charlie Chaplin, for instance, leaned lightly against a huge stone column, and immediately it fell to bits, I did not want him to say anything: no words of his could sober an event so stupendously drunk.

But more ambitious films, which pretend to give us comedy and drama, are less successful. You miss the sound of voices: you miss the presence of the living actors. The poorer the play is, the less you miss them. Thus, you can enjoy, for the few minutes of its existence, a sensational film, a bit of claptrap and swagger: but Heaven forbid that you should enjoy Shakespeare filmed, with scraps of words thrown on the screen at short intervals.

Judge the performance of a moving picture as you judge the performance of a gramophone. Each is a scientific toy: each produces an illusion, the one through our eyes and the other through our ears: and each gets its best results by staying inside its natural limits. Comic sounds, comic songs, swinging band-music with lots of brass and big drum in it, go well on a gramophone. But do you want to hear high-class music on it? Do you want to hear the voice of a dead friend on it? Not you: let it stick to being a gramophone: let it not profane either the music of the Immortals, or the voices of the dead.

III

The answer comes, that all this talk is tainted with self-conceit. That you and I are superior persons, forgetful of “the masses.” That the picture-palaces enliven the dullness of thousands of stupid little country-towns, and are a safe refuge of entertainment for legions of young men and young women who would have no other meeting-place but the streets. That moving pictures amuse the whole nation, and quicken the mind and widen the outlook and charm the leisure of countless lives more heavily burdened than yours and mine: lives of the hard-driven ill-educated “masses,” who cannot be expected to care for Shakespeare and the National Gallery.

And there is much truth in this answer. Only, it is a one-sided statement. If you could take the opinions of London working-women, with families of young children, just enough wages coming-in to keep a home over their heads, and a flaming picture-palace, with a lot of nasty trash on its programme, just round the corner, you would hear many opinions unfavourable to them rubbishy pictures: many descriptions of the children’s nerves upset by sham horrors, and the children’s pennies wasted on stuff which ought to be labelled Poisonous. The chief business of the palaces is to make money out of us. Where it pays them to give us rubbish, there they give us rubbish: where it pays them to raise a laugh over something disgraceful to us, there they set themselves to be blackguardly.

But praise them for that great gift which they, and they alone, can give to us. Moving pictures of real things, moving pictures of real life–we can never be too thankful for these. It is these, which are the new power come into the world. To watch, on the screen, every moment of the swing of waves and the dash of surf, every fleck of light on a river, every leaf stirring in the wind, is a grand experience: you find yourself watching them with more attention than you bestow on real water and real woods. For, on the screen, you are looking at pure movement, all by itself: you are not distracted by any thought of bathing in that sea, or of going on it: you just watch it, enjoying the mere sight of it moving.

In the display of moving pictures of real things, all the way up from elemental movement to human action, the picture-palace is our good friend: it is servant, by divine appointment, to reality. Moving pictures of living germs of disease, colossally magnified by the adjustment of micro-photography to the making of a film, are the delight of all doctors: moving pictures of wild creatures are the delight of all naturalists: scenes of human life in diverse parts of the world–the crowds in London streets, the crowds in Eastern bazaars, the work and play and habits and customs of the nations–these are the delight of all of us, and will never cease to delight us. For this wealth of visions, this treasury of knowledge, let us be properly grateful.

Only, the higher we go, the more careful we must be to exercise restraint and reverence. It is one thing, to film dumbshow, and another thing, to film real life and real death. Of living men, whom shall we film, and under what conditions, that we may pay sixpence to see them without loss of dignity in them, and without loss of reverence in ourselves? Crowds are not the difficulty: for they are comedy: but we ought to think twice before we film the tragedy of a crowd of people scared or starved. The difficulty is with single figures of great men, or a little group of them, or a multitude of men employed in the business of a great tragedy. Have we any rule, in this matter, to guide us?

During the last few weeks–here is mid-September–we have been made to think over these questions, by the proposal to film the Cabinet, and by the exhibition of the Somme pictures.

The proposal to film the Cabinet was abandoned. The plan was not to film a real Cabinet Council, but to film the Members of the Cabinet, in the Council-room, looking, more or less, as if they were holding a real Council.

Thus, it would have been a picture of real life, but of real life posing for the camera. His Majesty’s Ministers would have put themselves under some of the conditions of acting for a picture-play. This they would have done to please us: they would have shown themselves to us, looking just as they look when they are at work for us. The objection was raised, that the Cabinet would lose dignity: you will find a parallel passage in Shakespeare: and the point for us here is, that the value of a moving picture of a great man is lowered, if he is posing for it. There is no man too great to be filmed, if only he be unconscious of the process, or absolutely indifferent to it: but it is said that the one King who has posed in a group taken for his political advantage is Ferdinand of Bulgaria. Sic oculos, sic ille manus, sic ora ferebat. Much comfort will his people have of this moving picture of him, six months hence.

But the Somme pictures: the official pictures, taken for our Government, of the advance on the Western Front. A moving picture of a little group of great men, behaving as the camera expects them to behave, might deservedly fail to have power over us. But here are legions of men, not under orders from the camera, but employed in a business of tragedy such as the world has never suffered till now: men great, not in the Westminster-Abbey sense of the word, but in the greatness of their purpose, in their unconquerable discipline, their endurance: they go into the presence of Death without looking back, and they come out from it laughing, some of them: you see them treading Fear under their feet, you see Heaven, revealed in their will, flinging itself on the screen. You and I, safe and snug over here, let us receive what they give us, their example.

Be content to see these pictures once: they are too tragic to be taken lightly: but see them, if it be only to understand what the picture-palaces might achieve for your country. That which began as a scientific toy has become a world-power. Certain firms, preferring money to honour, have turned it to vile uses, and have proved themselves to be enemies of the people. But things will mend: they will mend very slowly, but the War will help them to mend: and the picture-palaces will gradually learn to take us seriously, and to play down to us less, and up to us more.

Comments: Stephen Paget (1855-1926) was a British surgeon and essayist. The Cabinet film referred to was an abortive attempt by Cecil Hepworth in 1916 to film the British cabinet as though in session, apparently cancelled after advance notice of the plans caused ridicule in some circles (though Hepworth did successfully film a series of ‘interviews’ with British politicians that same year). The ‘Somme pictures’ refers to the British documentary feature The Battle of the Somme (1916). My thanks to Nick Hiley who first drew this essay to my attention.

Links: Copy of I Sometimes Think at Internet Archive

Copy of ‘Moving Pictures’ essay at Gaslight

Discussion of the essay at The Bioscope