Source: Charles Edward Russell, Unchained Russia (New York/London: D. Appleton, 1918), pp. 300-305

Text: But as to what we call morals; of course the standards of the Nevsky Prospekt after sundown are reflected in the powerful Russian literature and the extraordinary Russian drama. There are those among us that are willing to take the Russian novel as it is and slip off our Puritan scruples for the sake of the Russian novelist’s unequaled grasp upon the vital and the moving; for when you read him it is as if one of Bret Harte’s “jinnies fierce and wild” had reached out of space and caught you irrevocably by the heart. And as to the drama, if I may make any fair guess, that is no more than beginning, and another generation is likely to see Russian plays that will set the world agape, morals or no morals. But I speak of the people as they are today, and according to all tradition and theory one of the best reflexes of their mental state should be found in a typical audience at a theater or a typical group of spectators at a film show.

But I solemnly swear to you I went out upon such a hunt and returned but little wiser. There was at one of the larger film theaters of Petrograd when I was there a moving-picture show that certainly should bring out a people’s mental processes, if anything of that kind could. It was a version of the Russian Revolution and the story of Rasputin. Morals aside, once more, the thing was exceedingly well done; there is no question about that. The acting seemed to be superbly spirited; the stirring scenes of the Revolution were put on with endless accessories, great crowds and potent realism. Night after night the theater was packed with people. They sat there and gazed upon vivid picturings of the most colossal drama in modern history and of the strangest and weirdest tale ever told, and for emotion might as well have been graven of stone.

I could not then explain this fact and do not pretend to explain it now. I went back to the place more than once to make sure, and I talked with others that went, some of them as much puzzled as I, and it was always the same story. The people sat absolutely unmoved before scenes that one would think would stir them to their depths. There was every kind of strong, if primitive, emotion in that play; also everything calculated to appeal to the revolutionary spirit of revolutionists and the reactionary spirit of reactionaries, and nobody seemed to be either glad or mad.

They saw the alleged relations between Rasputin and the late Czarina indicated with a frankness and lack of reserve that might have appalled a crowd of Westerners, but these apparently were neither shocked nor pleased. They saw the late Czar depicted as dull, sensual, cruel and as his wife’s degraded dupe, and if there were monarchists in the company they did not care, and if there were republicans they suppressed their elation. They saw the Czar signing his abdication and surrendering the throne of his ancestors and were unconcerned. They saw the uprising of the people, the dawn of liberty, the fighting in the streets, the triumph of democracy, the long-looked-for day come at last, the long processions of cheering multitudes, and gave never a hand-clap.

I could never well understand that play. The author might with equal reason be believed to have planned it to awaken enthusiasm for the Revolution or sympathy for the deposed and worthless tribe of Romanoffs — I never could tell which. The Czar in the earlier scenes was represented as unattractive, but the last scenes seemed intended to make him a martyr and a figure of cheap pathos, if anybody cares for that. He is a prisoner in his palace; he paces up and down with bent head, and then tries to pass out of a doorway. Two soldiers, with bayonets advanced, halt him. He nods his head and sighs, and then paces around to another door and two other soldiers halt him there. Then he draws apart the window curtains and looks sadly into the street where the people are celebrating the Revolution, and the end of it is a “close up” of him in that position.

One night a young officer, pointed out to me as the son of a noble, shed tears at this rather mawkish scene, but the rest of the people did not cry nor seem to care. It was plain that they were interested, but whatever emotions they felt they successfully concealed.

On another occasion I saw a film of a celebrated American comic hero of the movies whose impossible and galumphing antics have made millions roar in this country, and he did not seem funny to the Russians. They observed him chasing cannon-balls and dancing on his head and did not even smile. This time it was plain they were bored by the show. They talked and moved restlessly about and cracked sunflower seeds, and some went out, a signal proof of disapprobation, for the Russian is thrifty; he will not easily spend money for a show and then leave it.

Yet a few nights later I saw an audience composed of about the same class of people made ecstatic by a vocalist. He sang very effectively some Russian folksongs and the people cheered him with a sincerity of feeling that any performer might be proud to evoke. They were discriminating, also; they knew good singing from a poorer offering; they were not carried away by any bare appeal of the song itself. Being singers themselves they had reason to know the real from the counterfeit. A little later they would hardly give a hand to a performer that they thought fell short of a laudable standard.

It was a very large audience and a program that began at 8:30 P.M. lasted until 1 A.M., which in summer is no unusual time for these entertainments to close. A man made the audience cry with the way he read a simple little poem. I doubt if anybody could make an American audience cry with the same thing. Another man made them laugh with a comic sketch of his own composing. I think this was the most interesting part of the performance. The sketch being new there was an unusual chance to see how the minds of the people worked upon a humorous suggestion and they seemed to work like a steel trap. They seized the idea the instant it left the speaker’s lips.

They laughed at funny lines, wept at a poem about a little girl in the snow, and looked with considerable indifference on film-show antics of a high-priced and favorite entertainer.

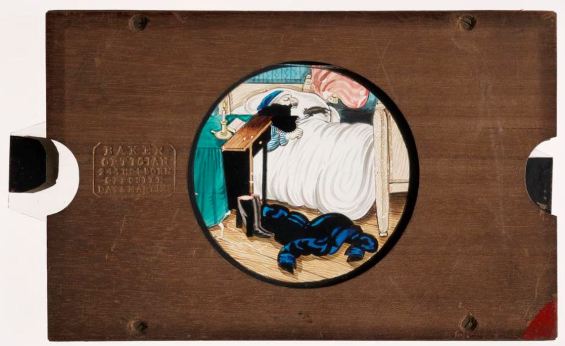

Comments: Charles Edward Russell (1860-1941) was an American journalist and prominent socialist. He was a member of Elihu Root’s American mission to Russia in June 1917, which offered America support to Kerensky’s Provisional Government. Russell was impressed by the influence of film on Russian audiences and pressed for American propagandists to produce films for Russian consumption. The film he describes could one of a number of Russian films at this time which dramatised the falls of the Romanovs, with a particular focus on the antics of Rasputin (e.g. Tsar Nikolai II, 1917). Russell would later appear in the American feature film The Fall of the Romanoffs (USA 1918) as himself, in a scene filmed outside the Duma during his time in Petrograd. I cannot identify the American comedian to whom he refers.

Links: Copy at the Internet Archive