Source: Malcolm Lowry, Under the Volcano (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1962 [orig. 1947]), pp. 30-32

Text: He stood, out of breath, under the shelter of the theatre entrance which was, however, more like the entrance to some gloomy bazaar or market. Peasants were crowding in with baskets. At the box office, momentarily vacated, the door left half open, a frantic hen sought admission. Everywhere people were flashing torches or striking matches. The van with the loudspeaker slithered away into the rain and thunder. Las Manos de Orlac, said a poster: 6 y 8. 30. Las Manos de Orlac, con Peter Lorre.

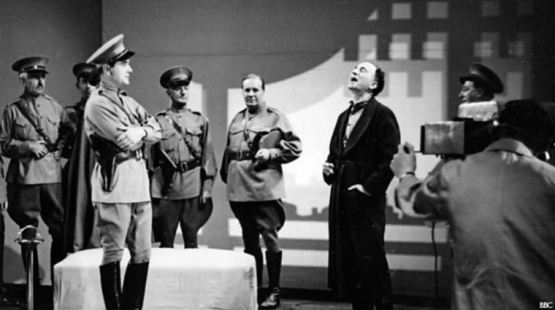

The street lights came on again, though the theatre still remained dark. M. Laruelle fumbled for a cigarette. The hands of Orlac . . . How, in a flash, that had brought back the old days of the cinema, he thought, indeed his own delayed student days, the days of the Student of Prague, and Wiene and Werner Krauss and Karl Grune, the Ufa days when a defeated Germany was winning the respect of the cultured world by the pictures she was making. Only then it had been Conrad Veidt in Orlac. Strangely, that particular film had been scarcely better than the present version, a feeble Hollywood product he’d seen some years before in Mexico City or perhaps – M. Laruelle looked around him – perhaps at this very theatre. It was not impossible. But so far as he remembered not even Peter Lorre had been able to salvage it and he didn’t want to see it again … Yet what a complicated endless tale it seemed to tell, of tyranny and sanctuary, that poster looming above him now, showing the murderer Orlac! An artist with a murderer’s hands; that was the ticket, the hieroglyphic of the times. For really it was Germany itself that, in the gruesome degradation of a bad cartoon, stood over him. – Or was it, by some uncomfortable stretch of the imagination, M. Laruelle himself?

The manager of the cine was standing before him, cupping, with that same lightning-swift, fumbling-thwarting courtesy exhibited by Dr Vigil, by all Latin Americans, a match for his cigarette: his hair, innocent of raindrops, which seemed almost lacquered, and a heavy perfume emanating from him, betrayed his daily visit to the peluquería; he was impeccably dressed in striped trousers and a black coat, inflexibly muy correcto, like most Mexicans of his type, despite earthquake and thunderstorm. He threw the match away now with a gesture that was not wasted, for it amounted to a salute. ‘Come and have a drink,’ he said.

‘The rainy season dies hard,’ M. Laruelle smiled as they elbowed their way through into a little cantina which abutted on the cinema without sharing its frontal shelter. The cantina, known as the Cervecería XX, and which was also Vigil’s ‘place where you know’, was lit by candles stuck in bottles on the bar and on the few tables along the walls. The tables were all full.

‘Chingar,’ the manager said, under his breath, preoccupied, alert, and gazing about him: they took their places standing at the end of the short bar where there was room for two. ‘I am very sorry the function must be suspended. But the wires have decomposed. Chingado. Every blessed week something goes wrong with the lights. Last week it was much worse, really terrible. You know we had a troupe from Panama City here trying out a show for Mexico.’

‘Do you mind my – ‘

‘No, hombre,’ laughed the other – M. Laruelle had asked Sr Bustamente, who’d now succeeded in attracting the barman’s attention, hadn’t he seen the Orlac picture here before and if so had he revived it as a hit. ‘¿ – uno – ?’

M. Laruelle hesitated: ‘Tequila,’ then corrected himself: ‘No, anís – anís, por favor, señor.’

‘Y una – ah – gaseosa,’ Sr Bustamente told the batman. ‘No, señor,’ he was fingering appraisingly, still preoccupied, the stuff of M. Laruelle’s scarcely wet tweed jacket. ‘Compañero, we have not revived it. It has only returned. The other day I show my latest news here too: believe it, the first newsreels from the Spanish war, that have come back again.’

‘I see you get some modern pictures still though,’ M. Laruelle (he had just declined a seat in the autoridades box for the second showing, if any) glanced somewhat ironically at a garish three-sheet of a German film star, though the features seemed carefully Spanish, hanging behind the bar: La simpatiquísma y encantadora Maria Landrock, notable artista alemana que pronto habremos de ver en sensacional Film.

‘ – un momentito, señor. Con permiso …’

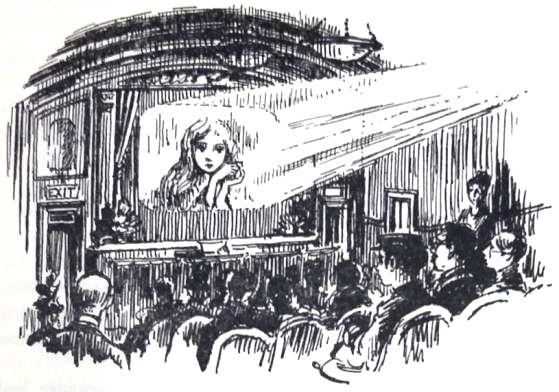

Sr Bustamente went out, not through the door by which they had entered, but through a side entrance behind the bar immediately on their right, from which a curtain had been drawn back, into the cinema itself. M. Laruelle had a good view of the interior. From it, exactly indeed as though the show were in progress, came a beautiful uproar of bawling children and hawkers selling fried potatoes and frijoles. It was difficult to believe so many had left their seats. Dark shapes of pariah dogs prowled in and out of the stalls. The lights were not entirely dead: they glimmered, a dim reddish orange, flickering. On the screen, over which clambered an endless procession of torchlit shadows, hung, magically projected upside down, a faint apology for the ‘suspended function’; in the autoridades box three cigarettes were lit on one match. At the rear where reflected light caught the lettering SALIDA of the exit he just made out the anxious figure of Sr Bustamente taking to his office. Outside it thundered and rained.

Comments: Malcolm Lowry (1909-1957) was a British novelist and poet, best known for his 1947 novel Under the Volcano. The novel is set around the Day of Death in Mexico at the end of the 1930s, and culminates in the wretched death of British ex-consul Geoffrey Firmin. One of the characters is Laruelle, a filmmaker, who has had an affair with Firmin’s film star wife. The novel contains many references to cinema, including pointed mentions of the 1935 American film Mad Love, also known as The Hands of Orlac, starring Peter Lorre. It was a remake of the 1924 Austrian film Orlacs Hände, starring Conrad Veidt.