Source: Harold B. Allen and Joseph Upper, At the Movies: A Farcical Novelty in One Scene (New York: Samuel French, 1921)

Text:

CAST

The Man in the Aisle Seat.

Mr. Griggs, who has seen the picture before.

Mrs. Griggs.

Clarice, a devotee of the pictures.

Nell, her cousin from up-state.

SETTING

Any back drop or plain curtain will serve as a set, as the action takes place in the subdued light, as in a motion picture theatre. A row of common chairs will serve as the seats, but if a row of regular theatre chairs can be procured, the realism will be heightened. The light, while subdued, should be sufficient to reveal the features of the several actors. The music of the piano, or piano and drums, is off stage, and should be at all times incidental to the dialogue.

CHARACTERS

The Man in the Aisle Seat, a middle-aged person, ordinarily well dressed. He is essentially a suburban type, as is evidenced by his shopping bag and numerous bundles. As this character is developed through pantomime almost entirely, the details of the type must be worked up through the ingenuity of the actor to a great measure.

Mr. Griggs, a typical, well-dressed, prosperous, middle-class business man, who is bored throughout the entire performance and who takes only a listless interest in the development of the plot of the motion picture story.

Mrs. Griggs, of the same general class represented by her husband. She should be dressed either in a suit, or in a house dress, adapted for informal evening wear, and should wear a hat and rubbers and gloves. Her attitude through the action is in direct contrast to her husband, as she maintains a lively interest throughout.

Clarice, a typical boarding school girl, about i8 years of age, very well dressed and stylishly in a street suit, hat, furs, etc.

Nell, a small-town type, neatly dressed, but not so stylishly as her cousin Clarice. Her costume should be slightly out of style to contrast to her more elegant cousin.

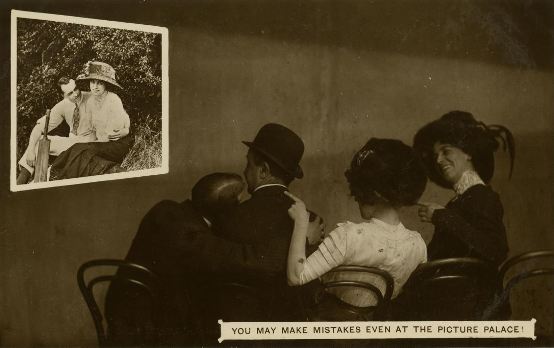

“At the Movies”

Scene: A row of chairs in any motion picture theatre.

The action of the piece takes place in a row of chairs in a motion picture “palace” during the presentation of a five-reel picture, “The Rose of Romany.” Any plain drop will serve as the back drop for the shallow stage required, as the action takes place in a subdued light as in a theatre. A row of five theatre chairs are required. The music, which accompanies the conversation, paralleling the course of the picture, should follow the story, but should at all times be secondary to the dialogue, it being introduced merely to heighten the realism of the scene.

The row of chairs is empty when the action starts. A man, carrying a net shopping bag, filled with bulky parcels, and with his arms filled with other bundles, enters at the right, and takes the aisle seat at the right, placing his shopping bag under the seat and holding the other bundles in his lap. He wipes his face with his handkerchief, sighs with relief, and settles down to an hour and a half of enjoyment, when Mr. and Mrs. Griggs, a typical middle-aged couple, enter. He pilots her to the row of seats.

Mrs. Griggs. It’s so dark in here … I can’t see a thing.

Mr. Griggs. Here you are. This is all right.

Mrs. Griggs. (Indicating back of row) Here?

Mr. Griggs. (Pushing her forward) No. Here.

Mrs. Griggs. I can’t see a thing. (She puts her hand on the head of the man in the aisle seat) Oh, I beg your pardon. It’s terribly dark.

Mr. Griggs. Right in here. That’s it. (He hands her past the man, who has to pick up his shopping hag, lift it out into the aisle, and then step out himself, clinging all the while to the other bundles. When Mr. and Mrs. Griggs have passed in, he moves back, and settles himself again)

Mrs. Griggs. Oh, George, there are two seats, just a little way ahead. (Indicating seats ahead) Don’t you think … ?

Mr. Griggs. No, no, this is all right.

Mrs. Griggs. I know, but … Oh, do let’s take those two.

Mr. Griggs. (Rising) Oh, all right.

(The man on the aisle is compelled to rise once more, and move his excess baggage and himself out into the aisle. Mr. and Mrs. Griggs start forward to take possession of the other two seats.)

Mrs. Griggs. (Stopping short with an exclamation of disappointment) Oh, isn’t that horrid. That young couple has taken them. (To Mr. Griggs. who has pointed out some other seats) No, I won’t go any further forward. We’ll just stay where we were.

Mr. Griggs. But, my dear … (He looks helplessly from her to the man in the aisle seat. The latter is used to it, however, and once more moves himself and his many bundles to allow them to pass in) I’m sorry. Sir, I’m sure.

The Man. ‘S all right.

Mrs. Griggs. Yes, we’re awfully sorry to have to trouble you. (She takes the third seat from the aisle, as Mr. Griggs takes the second) Is there anybody behind us? I suppose I’ll have to take off my hat. (She does so grudgingly, and arranges her hair)

(Enter Clarice and Nellie. Clarice is a boarding school girl, and Nellie is her small town cousin, each about 18 years.)

Clarice. In here, Nell, there’s two. That’s just about right, not too far front or anything. (To the man) Excuse us, please.

(Again the weary occupant of the aisle seat is compelled to move, together with his property. The girls pass in.)

Mrs. Griggs. (Who has to stand) Oh, dear. Clarice. (Sweetly to Mr. Griggs) Thank you. All right, Nell. (They take the fourth and fifth seats, Clarice the fourth and Nell the fifth from the aisle) We’re just in good time. The feature hasn’t started yet. I wonder what they’re showing? Oh, they’re the announcements for next week — Special Added Attraction. Fatty Arbuckle in “Heavier Than Thou.” Oh, I’ll bet he’ll be funny in that. “Heavier Than Thou” instead of “Holier Than Thou,” don’t you see, Nell? “Elsie Ferguson in Repenting at Leisure.” Oh, she’s wonderful, Nell. I just love her. You know she made a great success in the legitimate before she went into the pictures. There was a long article about her in the Weekly Flicker last week. She’s married, you know. There was a picture of her with her husband. I’ve seen her on the stage, too. The whole class at school went one afternoon to see her play “Portia” … you know, in the “Merchant of Venice.” It was a special performance. Benefit, I think. Oh, “Pauline Frederick in La Tosca, Wednesday and Thursday.” Oh, she ought to be good in that. It’s French, you know, and it means … I can’t think just now what Tosca does mean. The something-or-other.

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “Grace Geary in the Rose of Romany in Five Parts.” It just seems as if I had seen this before. It was the Rose of Something, but it couldn’t have been this, for Grace Geary wasn’t in it.

Clarice. Oh, “Grace Geary in the Rose of Romany.” I’m so glad you’re going to see her, Nell. She is simply wonderful in emotional roles. I saw her last Saturday with Kensington Dreadnaught in “Ashes of Fate.” She was wonderful. She is going to do serials next year for Pathe. I’m just crazy to see her in them.

Nell. “The Rose of Romany, the Pride of the Gypsies, Grace Geary.” Oh, I know I am going to like it. She’s got such a wonderful face. (Confidentially) Is that her real hair, Clarice?

Clarice. Yes, isn’t it lovely? I just love the way she wears it.

Mr. Griggs. I have seen this thing before.

Mrs. Griggs. You have, dear. Where?

Mr. Griggs. Oh, one day last week. After lunch. Had a customer on my hands and had to do something.

Mrs. Griggs. Is it good, George?

Mr. Griggs. Oh, pretty fair. I don’t especially care for her.

Mrs. Griggs. Oh, I think she is a dear little actress. (Reading) “Lord Edgemont, Earl of Bellefair, the Last of An Old Family, Wallis Fairfield.”

Clarice. Wallis Fairfield. Oh, I’m so glad he’s back again.

Nell. (Innocently) Where’s he been?

Clarice. Why, didn’t you know he was almost killed when his automobile ran off a cliff?

Nell. I think I saw that in a picture at the Wonderland Theatre at home. In the “Tiger’s Claw,” wasn’t it?

Clarice. Heavens, no. Wally Fairfield doesn’t play in serials like that. It was on his honeymoon.

Nell. He’s married, then.

Mrs. Griggs. “The Honorable George Dorsay, a friend of the Earl’s, Thomas Hannibal.” Oh, George, doesn’t he look something like your Uncle Horace Griggs? Don’t you think so? Of course, your uncle is an older man. He doesn’t look so young himself, though, does he?

Mr. Griggs. You can’t tell anything about it in the pictures.

Mrs. Griggs. (Weakening) But I think he does. The eyes …

Clarice. (Reading) “Led by the Hand of Fate, Lord Edgemont, the Master of Bellefair, and his Friend, the Honorable George Dorsay, ride through the Wooded Paths of the Earl’s Estate.”

Nell. Isn’t that lovely, Clarice? Where do you suppose that’s taken? In England?

Clarice. No, in Jersey probably.

Nell. You mean in New Jersey State?

Mrs. Griggs. They ride well, don’t they, George? And such pretty horses! Bays, aren’t they? That’s what they call brown horses, isn’t it?

Mr. Griggs. Yes, yes.

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “Fate in the Guise of a Gypsy Girl Crosses Their Paths,”

Nell. Oh, she’s going to tell their fortunes. (Pause) I don’t believe she’s telling anything good,

though, do you, Clarice?

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “The Gypsy Foresees Dorsay’s Death.” Oh, this starts out awfully sad.

Mr. Griggs. You’ll see she was right. It’s his heart.

Mrs. Griggs. Well, he doesn’t look a bit strong. Your Uncle Horace’s heart was affected, too. My, this man does look like him, George.

Clarice. (Reading) “In Edgemont’s Palm the Gypsy Reads Coming Happiness.”

Nell. He doesn’t look as if he believed her, Clarice. Of course, she really doesn’t know.

Clarice. Oh, but they do. We had our fortunes told at school last Hallowe’en by a real palmist, and she told one of the girls that she would be married before the term was over, and you know she would have been if her people hadn’t found out, and made her wait until she had finished school.

(The man on the aisle loses consciousness and rests his head on Mr. Griggs’ shoulder. Mr. Griggs seeks to rid himself of the burden by pushing the sleeping man back into his chair, but in doing so he distracts Mrs. Griggs’ attention from the screen.)

Mrs. Griggs. What’s the matter, George?

Mr. Griggs. The man on the aisle.

Mrs. Griggs. (In a stage whisper) Has he been drinking?

Nell. Oh, what beautiful horses. They’re going hunting.

Clarice. (Reading) “Edgemont promises Dorsay that He will be a Father to the Latter’s Only Son, Should Misfortune Overtake Dorsay.” You see, Nell, he’s afraid that the gypsy told the truth about misfortune overtaking him. You know.

Nell. You mean when the gypsy told his fortune?

(There is a lull of a moment. The piano plays a hunting song, and the drummer imitates the hoofs of horses.)

Mrs. Griggs. (Jumping) Oh, oh, oh, I hope he isn’t killed.

Mr. Griggs. Sh-h-h-h. You’ll wake up our friend here.

Nell. Oh, Claire, do you suppose that is what the gypsy meant?

Clarice. Didn’t I tell you she knew? (Reading) “The Gypsy’s Grim Prophecy is Fulfilled.”

(Slow funeral music follows.)

Nell. I like the music here, don’t you? It’s what they call a dead march, isn’t it?

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “The Party Seeks the Aid of the Gypsies.”

Nell. Isn’t that the same gypsy that told the fortunes?

Clarice. No, that’s Grace Geary.

Mrs. Griggs. Lovely large eyes, hasn’t she, George ?

Mr. Griggs. What’s that?

Mrs. Griggs. I say she has lovely large eyes, hasn’t she?

Mr. Griggs. Yes-s.

Clarice. (Reading) “In the Daughter of the Gypsy Chieftain Edgemont Discovers for the First Time the Meaning of Love.”

Nell. But, she’s a gypsy …

Clarice. Oh. Donald Dundeen is playing the gypsy chief. He is so virile and everything.

Nell. Isn’t he, though? I think I’ve seen him, too — in something.

Clarice. He always plays such strong characters. I love his face. It’s so manly. (Reading) “Under the Pretext of Asking Rose to Dance for His House Guests the Earl Invited the Gypsy Maid to Bellefair Manor.”

(Dance music follows, to which everyone unconsciously beats time. The man on the aisle wakes and watches the picture with great interest.)

Mrs. Griggs. She dances well, doesn’t she, dear? Very pretty and graceful.

Mr. Griggs. Yeah.

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “The Earl Seeks the Seclusion of the Garden to Tell Rose of His Great Love.”

Nell. (Raving) I love this.

(The three women sit wrapt in the ecstasy of a love scene. The man on the aisle goes to sleep again. The music is soft and ingratiating.)

Clarice. (Breaking the silence) “The Marriage of the Earl to the Gypsy Maid at the Parish Church Provides Gossip Aplenty for the Villagers.”

Nell. They’re going to the church now, aren’t they ? In the family carriage. I don’t think he looks very happy, though, do you?

Mrs. Griggs. This is a very pretty picture, George, but I don’t think the marriage will be a happy one. Those kind never are.

Mr. Griggs. It isn’t, you’ll see.

Mrs. Griggs. (Satisfied) I knew it wouldn’t be.

Nell. Oh, he’s giving her some beads.

Clarice. Pearls, you mean. Aren’t they lovely, though? I love pearls.

Nell. Oh, yes, Mrs. Graham at home has got a lovely string of real pearls.

Clarice. (Reading) “The Earl Bestows On His Young Bride the Edgemont Pearls, the Heritage of Generations.”

(The piano plays the “Rosary,” and everyone is impressed by the timeliness of the music.)

Nell. “The Rosary.” We’ve got that on the Victrola at home.

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “In the Months That Follow One After Another, Rose Learns That the Earl is Tiring of Her Charms.” That’s just what I said, isn’t it, George, it wouldn’t be happy!

Nell, Oh, who’s that, Clarice?

Clarice. That’s the gardener. Just a minor role. You see he is trying to sympathize with her now that the Earl …

Nell. She looks so sad, doesn’t she? Even when the gardener brings her roses.

Mrs. Griggs. There’s a lot to this picture, George ; don’t you think so ? It shows that riches don’t bring happiness after all. (She sighs)

Nell. Oh, what lovely dresses.

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “Another Hunting Season Rolls Around and London Society is Again the Guest of Bellefair Manor.” I don’t see his wife — Rose — anywhere. Has she left him or anything?

Mr. Griggs. You’ll see in a minute.

Mrs. Griggs. Oh, there she is in her boudoir. (Reading) “Goaded to Despair By the Snubs of the House Guests, Who Cannot Forget That She is a Gypsy, Rose Refuses to Play the Role of Hostess at Dinner On the Eve of the Hunt.” Well, you can’t really blame her, can you? Right in her own house, too.

Nell. She doesn’t seem very happy, does she? But I do like that dress.

Clarice. No, you see … (Reading) “The Earl, After Upbraiding Her for Her Attitude Toward the Guests, Leaves Her in Displeasure.”

Mrs. Griggs. He’s a perfect brute, isn’t he? (Reading) “Lady Edgemont is Indisposed, and Begs to Be Excused.” What a lie!

Nell. I don’t see what he said that for, though, she isn’t …

Clarice. Don’t you see, he couldn’t very well come right out and say that she refused to come to dinner, because she was angry at the way they had treated her.

Nell. She’s going to write a note. What a pretty writing desk!

Clarice. Oh, did I tell you that father has promised to get me a writing desk for my room for a graduation present. Isn’t that lovely, Nell?

Nell. Yes. Oh, look.

Mrs. Griggs. (Reading) “Good-bye, forever. You will be happier when I am gone.”

Nell. (Simultaneously with Mrs. Griggs) “Good-bye, forever. You will be happier when I am gone. I hope you may forget and forgive. We will never meet again. Rose.”

Mrs. Griggs. (Continues reading) “I hope you will forget and forgive. We will never meet again. Rose.”

(Tosti’s “Good-bye” is played. There is a pause.)

Nell. She is taking her last look. What’s she going back for? Oh. the pearls.

Mr. Griggs. (Shrugging his shoulders) You never catch a woman forgetting her jewelry.

Mrs. Griggs. Oh, of course, he’ll come back when the bird is flown.

Nell. The note is right in plain sight. D’you suppose he sees it?

Clarice. Of course. See, he’s picking it up now. (Reading) “Good-bye, forever. You will be happier when I am gone. I hope you may forget and forgive.”

Mrs. Griggs. Serves him right.

Nell. She’d be sorry now if she could see him.

Clarice. What a wonderful actor, I think. So restrained.

Mrs. Griggs. This is very much like a picture I saw this afternoon. Only in that the wife didn’t leave her husband, but she was tempted to. It was Constance Conner, and she is so emotional. The husband in that is a broker or a banker, on Wall Street, you know, and he neglected his wife for business. It was a splendid picture, George, very clean and moral. I know you would have enjoyed it, George.

Mr. Griggs. Probably.

Clarice. (Reading) “The Passing of Remorseful Years.”

Mrs. Griggs. Well, I should think they would be remorseful.

Clarice. (Continues reading) “The Earl’s Sole Consolation for the Loss of His Wife is the Guardianship of His Late Friend’s Son.”

Nell. Oh, Clarice, isn’t he handsome?

Clarice. Perfectly stunning, I think. That’s Austin Hobbs. The Flicker says he is a potential star.

Nell. The gardener is the same one who was there before his wife left, isn’t he?

Mrs. Griggs. Why, that young man must be the son of the one who was killed out hunting, you know, In the first part of the picture. He does look like his father — something — don’t you think so, George?

Clarice. (Reading) “There Are Two Men Waiting to See You, Sir. Gypsies, I Should Say, Sir.”

Nell. Oh, do you suppose, Clarice …

Mrs. Griggs. Likely as not, George, these gypsies are of the same tribe as the Earl’s wife.

Mr. Griggs. Of course, they are, but they don’t know anything about him. You see they just want to camp on his land, on the manor, or whatever you call it.

Mrs. Griggs. Oh, I see. (Reading) “In the Absence of the Earl, Edgar Dorsey Allows the Gypsies the Privilege of Camping on the Estate.” But where is the Earl all this time?

Mr. Griggs. Oh, he’s away somewhere, I suppose.

Clarice. (Reading) “Lola, the Daughter of the Tribe, Grace Geary.”

Nell. But I don’t understand. I thought Grace Geary was the wife.

Clarice. She was; but she is playing a dual part.

Nell. Dual?

Clarice. Yes, you see she plays both the mother and the daughter. Lola is the daughter of Rose and the Earl.

Nell. Oh, I see. She must be a wonderful actress to do that. Oh, she’s going to tell his fortune now.

Mrs. Griggs. It don’t seem as if these gypsies do anything but tell fortunes.

Mr. Griggs. She doubles pretty well.

Mrs. Grigg. (Perplexed for the moment)

Doubles? Oh, you mean she plays both parts well. Yes, I think she is just fine.

Clarice. (Reading) “Under the Witchery of the October Moon Edgar Falls a Prey to the Charms of the Gypsy Girl.”

Mrs. Griggs. I suppose this is all going on without the Earl knowing anything about it.

Mr. Griggs. He’ll hear all about it. You’ll see.

Mrs. Griggs. Does it end happily, George?

Mr. Griggs. Sure, they all do.

(In the scene that follows the three women watch with greatest interest the love scene on the screen. Nell grasps her hands tightly together and sighs deeply. Mr. Griggs picks his teeth, and the man on the aisle watches the picture pathetically.)

Mrs. Griggs. (Breaking the silence by reading) “To-morrow I Will Ask the Earl for His Consent to Our Union. If He Should Refuse, I Will Leave All for You.” I can just about expect what the Earl will say.

Mr. Griggs. He comes through all right when he finds out who she is.

Nell. Oh, there’s the Earl now. He certainly does look stern. If I was Edgar, I wouldn’t want to ask him.

Clarice. (Reading) “Consent to Your Union With a Gypsy. Never!”

Nell. Where’s he going? The Earl, I mean.

Clarice. You’ll see if he isn’t going to order the gypsies off the estate. There, see. (She reads) “The Earl Goes to the Gypsy Camp to Order Their Departure From the Manor.”

Nell. Oh, see now. My, he is mad.

Mrs. Griggs. And he meets his own daughter there probably. There, I told you. See how he drops his cane the moment he sees her.

Clarice. You see, he recognizes Lola as his daughter. (Reading) “In the Eves of Lola, the Wandering Gypsy Girl, the Earl Sees the Eyes of Rose. His Girl Wife.”

Mrs. Griggs. (Moved to tears) This is a lovely picture; very touching.

Nell. There’s Edgar. Oh, he’s going to consent to it.

Clarice. Why, of course. Isn’t she his own daughter?

Nell. I think it is lovely the way it came out.

Clarice. (Reading) “Once Again the Villagers Flock to Their Doors to See the Carriage of the Earl Drive to the Parish Church, Bearing a Lovely Bride.”

Mrs. Griggs, It’s a lovely ending, too. I wonder if I wore rubbers, George; do you remember?

Mr. Griggs. You always do.

Mrs. Griggs. I thought I did. Oh, here they are. (She fishes them out from under the seat in triumph just in time to read) “In the Twilight of Life the Earl Sees in the Lives of Lola and Edgar the Happiness of Which He Dreamed.” (Pause) “The End.”

Clarice. Aw, “Rice Culture in Japan.” Let’s go. (She rises hastily)

Nell. Don’t you want to see it? (She gets up reluctantly)

Clarice. No, come on.

(They go out, compelling Mrs. Griggs, who is putting on her rubbers, to rise, and the man on the aisle to move out laboriously. When the man is just settled, Mrs. Griggs speaks.)

Mrs. Griggs. Probably this is an educational picture, George. Let’s not stay.

Mr. Griggs. All right.

(She puts on her hat, and he takes his from under the seat, and again the man on the aisle is obliged to surrender his seat, and allow them to pass. He moves back, and settles himself to become engrossed in the intricacies of rice culture, when the curtain falls.)

Comments: This is one of several comic sketches from this period written for amateur dramatic performance which mock the habits of movie audiences, in particular talking while the film is going on. Other examples are Minnie at the Movies and Maisie at the Movies. Fatty Arbuckle, Elsie Ferguson and Pauline Frederick were genuine film performers. The film titles are imaginary, but Pauline Frederick did appear in a film version of Tosca (in 1918),

Links: Copy at Internet Archive