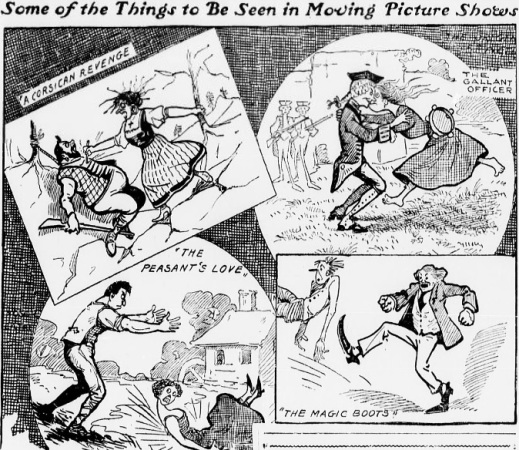

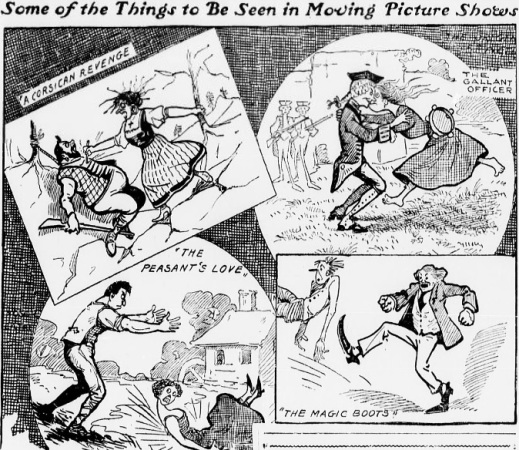

Illustration that accompanies the original article

Source: Charles Darnton, ‘This City has over 500 Moving Picture Shows: Do YOU Know WHY?’ The Evening World [New York], 16 January 1909, p. 9

Text: “I like to see a story.”

A long tramp bad led to a short answer. And the woman with a shawl about her head and a wide-eyed child clutching her hand was probably right about the appeal of the moving picture.

How wide this appeal has become may be judged from the fact that there are more than 500 moving picture shows in New York. From one end of the town to the other the “manager,” with little more than a lantern to his name, is holding the screen up to nature and occasionally turning a trick that goes nature one better. Although vaudeville audiences take the moving picture as their cue to move toward home, true lovers of art in action take all they can get for five or ten cents and then come back for more next day.

They like to see a story.

That’s the explanation – thanks to the woman with a shawl over her head. They feed upon mechanical fiction. They read as they look. Sensational melodrama, with the villain doing his worst in a plug hat, is an old story to them. They know it by heart. And so, theatres in which virtue used to take a back seat until the last act have felt the power of moving pictures. Only one remains to tell the blood-and-thunder tale in all Manhattan and it was obliged to get down to “workingmen’s prices” before it could compete with its noiseless rivals. From the start the moving picture show had a double advantage – lower prices and a daily change of bill. Then it went further and produced “talking pictures,” but in most cases this feature has been done away with audiences preferring to take their plays in peace and not be disturbed by the man behind the megaphone. What they want is action. Their attitude goes to show that it is always well to leave something to the imagination. They like to see a story from their own point of view.

In New York nearly every neighborhood has its “show,” and the craze has spread throughout the country until no town is too small to do the moving picture honor. Here, according to the word of a Sixth avenue showman, “picture fiends,” who keep a record of what they have seen and protest against “repeaters,” are an outgrowth of the craze. Their criticism of the Sunday exhibitions at which only educational pictures may be shown, in accordance with the stupid law, is often expressed in the simple term “Rotten!” They insist upon getting action for their money. The pictures must get “a move on” to win success. Patrons of the picture-drama want to see a story with plenty of action in it. From the Bowery to the Bronx tastes and pictures are much the same.

Bowery Wants Bank Robberies

But hero and there of course individual taste asserts itself. The proprietor of a little hall on the Bowery confessed that while his clientele showed a due appreciation of comedy and tragedy they had from time to time expressed a deep yearning for bank robberies. Unfortunately safe-cracking is not included in the picture-maker’s repertoire, and so the regretful “manager” has not been able to supply the demand for that particular form of art. However his audience made the best of things on a recent afternoon and seemed rather pleased with “A Corsican Revenge.”

The Corsican who caused all the trouble by killing a fellow fisherman and then got knifed by his victim’s wife, a husky lady with a fine stroke, looked like Caruso in “Cavalleria Rusticana.” According to the hospitable custom of the country, she was obliged to entertain her husband’s slayer when he sought refuge in her home. But once she got him outside she made short work of him. The lively little tragedy was worked out with neatness and dispatch. Five or six Chinamen who could qualify as Broadway first-nighters without putting on boiled shirts watched “A Corsican Revenge” without the slightest change of expression. In fact, the audience made no sign until two energetic gentlemen were flashed upon the scene and began kicking each other in the stomach. This light comedy was received with roars of laughter. The drummer emphasized each kick with a thump and the “professor” came down hard on the piano. “Comedy” won the occasions.

A placard on the wall warned the visitor to “Beware of Pickpockets.” Another made this polite request: Gentlemen Will Please Refrain from using Profane Language. The gentlemen did.

Accordion Breathes Hard.

In front of another temple of art across the street was the sign: “Positively No Free List During This Engagement.” You had to have a nickel to get inside. Down in front sat a Bowery artist with an accordion that was drawing its breath with great difficulty. During the overture he addressed facetious remarks to the audience.

“Hey, there!” yelled one of the crowd. “Cut out that comedy and give us some music.”

“Anyt’ing doin’?” inquired the performer, holding out his hat. “Come on, now,” he urged, ” trow in a little sumt’in fer de dear ones wot are dead and gone.”

“Ferget it!” yelled the unsympathetic mob.

“The Gallant Guardsman” presently drew attention from the accordion artist. At the first appearance of a Spanish soldier on the screen the accordion began wheezing “Die Wacht am Rhein.” When the guardsman rescued a dancing girl from the embraces of a low-browed citizen the tune changed to “Marching Through Georgia.” A dash of “Trovatore” cheered the guardsman on his way. The low-browed citizen waited behind a wall and killed the first soldier that came along. But he got the wrong man and the hero was about to be shot when the barefooted dancing girl ran to the rescue and explained the situation in a few hand-made gestures.

The audience followed the story with intense interest, and only the accordion was heard until a picture showing a young man who was carried off in a wardrobe appealed to the Bowery sense of humor. The hero of this adventure found himself in the bedroom of a loving couple who finally accepted his explanation and then had him sit down to supper with them.

French but Chaste.

All of the pictures seen on the lower east and west sides were French but chaste. Nothing more shocking than a murder occurred in any of them.

At a place in Grand street “The Peasant’s Love” was the chief feature of the bill. All went well until the peasant’s sweetheart promised to meet a newly arrived sailor “down by the pond.” His note to her was revealed on the screen. But the jealous peasant got to the pond first and when the girl came along he sneaked up behind her and threw her into the pond. The inevitable gendarmes first arrested the sailor, of course, but after a long chase they nabbed the guilty peasant.

Nearly all of the pictures showed gendarmes in pursuit of somebody. The principal figure was usually obliged to “run for it,” and suspense was kept up until the capture of the fugitive. The “story” was kept on the jump.

In “The Magic Boots” a happy individual was seen eluding his pursuers by walking on water, telegraph wires – wherever his fancy led him. His wonderful boots defied the French and all other laws. But down in Grand street it was the serious pictures that gripped the spectators.

“Dremma,” answered one manager when asked what appealed to his patrons most of all. And a woman whom he described as one of his best customers said: “I like to see a story. The funny pictures – they are funny, yes, but you don’t remember them. I like to remember what I see. You don’t forget a story – it goes home with you.”

Take Them Seriously.

This serious interest in story-pictures was apparent in other halls along Grand street. But a desire to be cheerful under all circumstances was suggested by this announcement over the door of one place: “The Bride of Lammermoor – A Tragedy of Bonnie Scotland.”

In a Mulberry street “theatre,” conducted under Italian auspices, the pictures were similar to those in Grand street. A coal stove filled the place with gas but no one seemed to notice it. Another Italian place in West Houston street sported this sign: “Caruso Moving Pictures.” But Caruso wasn’t among those present on the screen. The name, apparently, was merely a delicate tribute to the Metropolitan’s sobbing tenor.

Bessie Wynn’s name was prominently displayed in front of an imposing theatre in Fourteenth street. But Bessie was there only in voice and picture. You could recognize her picture but her voice had to be taken for granted. When they canned Bessie’s voice they evidently forgot to screw down the lid, and so it had soured and curdled and lost its flavor.

“The Wild Horse” filled up on oats at the Manhattan Theatre and developed from a weak skinny nag into a fat and fearful animal that kicked everything to pieces. It was the “big laugh.”

Harlem Likes to Laugh.

But here as elsewhere serious pictures with now and then a shooting or stabbing incident for excitement outnumbered the comic subjects. Harlem showed the greatest fondness for funny pictures. The Bronx appeared to be more serious minded.

Some of the places open their doors as early as 9 in the morning and keep going until after 11 at night. The shows are continuous and so are the privileges that go with a ticket. Only the pictures are compelled to move.

Comment: Among the films described are Âmes corses [The Corsican’s Revenge] (France 1908 p.c. Eclair) and Le galant garde français [The Gallant Guardsman] (France 1908 p.c. Pathé Frères). Bessie Wynn was an American singer and stage comedienne. The mention of ‘talking pictures’ presumably refers to a short vogue in a few theatres for having actors speak behind the screen rather than synchronised sound films (i.e. films, usually of singers, synchronised to a gramophone recording).

Links: Available online at Chronicling America