Source: Charles Dickens, ‘Moving (Dioramic) Experiences’, All the Year Round, vol. XVII, 23 March 1867, pp. 304-307

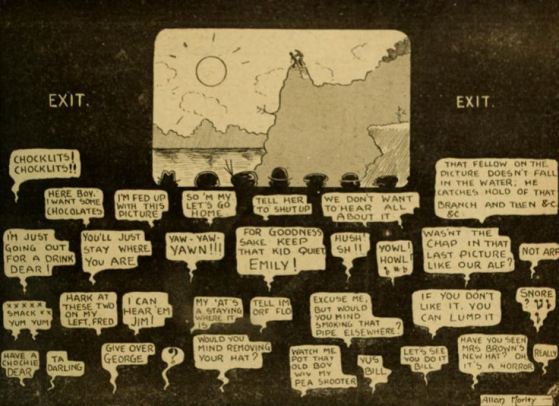

Text: The diorama is a demesne that seems to be strictly preserved for the virtuous and good. Those for whom the gaudy sensualities of the theatre are interdicted may here be entertained with the mild and harmless joys of an instructive diorama. At the doors going in, we may see the quality of the guests — benevolent-looking elderly men, dry virgins, a clergyman or two, and portly mammas with a good deal on their minds, who have brought the governess and all their young family. There is a crowd, and extraordinary eagerness to get in, though there, alas! often proves to be too much room. For these moral shows address themselves only to a limited area; though the limited area does not come forward so handsomely as it should do. Among such audiences there is a more resentful and jealous feeling about points of disagreement between them to the entertainment, such as not commencing — returning money and the like; the umbrellas and sticks, it may be remarked, are made more use of — I mean in the way of creating noise and the word “Shame!” is uttered from the back benches with more burning indignation. How often on the first night, say, of the Grand Moving Diorama of the Tonga Islands, when there has been a long delay, and something fatally wrong in the gasworks of the little town has prevented the despairing exhibitor from doing much more than show dim pictures, and transformations that miscarried dreadfully, how often have we not seen a bald head and glassy spectacles rise out of the Cimmerian gloom to which the character of the show inevitably consigns its audiences, and in what seems sepulchral accents address us on our wrongs. “We learn by our excellent weekly organ — not the one we hear in our place of worship — that this is Mr. Laycock, our “worthy” fellow-citizen, who has been for years a resident. He thinks we have been treated badly— outrageously; in fact, in the whole course of his long residence at Dunmacleary — then umbrellas and sticks give a round — he never recollected an audience — a highly intelligent and respectable audience (sticks and umbrellas again) — treated with such disrespect. What they had seen that night was a miserable and inefficient thing — a wretched imposture and take-in” (sticks again). The poor showman is always helpless, and from his “stand,” where he had been in such luxuriant language describing the beauties of foreign lands, excitedly defends himself, to cries of “No, no,” and umbrella interruptions. It was not his fault. He had arrived late “in their town.” He had been up all night (“Return the money”). It was the fault of their gasworks (groans), and he would mention names. Yes, of Mr. John Cokeleigh, the secretary (“Shame”), who assured him (great interruption at this unworthy attempt to defame the absent).

A really good diorama is a really high treat, and for the young an entertainment second only to the pantomime. Parents should encourage this feeling, instead of serving out those little sugar-plums, which are so precious to a child, as if they were dangerous and forbidden fruit, which might corrupt the morals and corrupt the soul. These joys are always made to hang awfully in the balance on the turn of a feather-weight, as it were — by well-meaning but injudicious parents.

Alas! do I not recal Mr. Blackstone, our daily tutor, a steady, conscientious, poor, intellectual “navvy,” who was reading nominally “for orders,” but, as it proved, for a miserable curacy, which he still holds, and I believe will hold, till he reaches sixty. This excellent man kept a mother and sisters “on me and a few more boys,” that is to say, by coining for two hours each day on tutorship. Mr. Blackstone kept a little judgment-book with surprising neatness, in which are entries which scored down, with awful rigidness, Latin, bene; Greek, satis; French, medi. This volume was submitted every evening at dinner to the proper authority, and by its testimony we were used according to our deserts, and, it may be added, with the result which the rare instinct of the Lord Hamlet anticipated on using people after their deserts. During this course of instruction, it came to pass that the famous Diorama of the North Pole arrived in our city. It had indeed been looked for very wistfully and for a long time, and its name and description displayed on walls in blue and white stalactite letters, apparently hanging from the eaves of houses, stimulated curiosity. Indeed, I had the happiness of seeing the North Pole actually arrive, not as it might be present to romantic eyes, all illuminated from behind, and in a state of transparent gorgeousness, but in a studied privacy and all packed close in great rolls. Later, I found my way up the deserted stair of the “rooms” where the North Pole had taken up its residence, and, awe-struck, peeped into the great darkened chamber where it reposed with mysterious stillness. There was a delightful perfume of gas, and the rows of seats stretched away far back, all deserted. The North Pole, shrouded in green baize, rose up gauntly, as if it were wrapping itself close in a cloak, and did not wish to be seen. A hammer began to knock behind, and I withdrew hurriedly. Somehow, that grand déshabille by day left almost as mysterious, though not so gay, an impression as the night view. But to return to Mr. Blackstone. Latterly, rather an awkward run of “satis” and “medis” had set in, and the pupil at that evening’s inspection of the books had been warned and remonstrated. With that rather gloomy view which is always taken of a child’s failings, he had been warned that he was entering on a course that would bring him early “to a bad end,” if not “to the gallows.” This awful warning, though the connexion of this dreadful exit with the “satis,” &c., was but imperfectly seen, always sank deep, and the terrors of the “drop” and a public execution sometimes disturbed youthful dreams. But, however, just on the arrival of the North Pole it was unfortunate that this tendency towards a disgraceful end should have set in. For the very presence of this pleasing distraction unnerved the student. It was determined that an early day should be fixed when the family should go, as it were, en masse, and have their minds improved by the spectacle of what the Arctic navigators had done. To the idle apprentice who was under Mr. Blackstone’s care, it was sternly intimated that unless he promptly mended, and took the other path which did not lead to the gallows, he should be made an example of. This awful penalty was enough from sheer nervousness to bring about failure, and when the day fixed for the North Pole came round, Mr. Blackstone said “it was with much pain that he was compelled to give the worst mark in his power for Greek, namely, ‘malè!'”

At this terrible blow all fortitude gave way, and, with a piteous appeal to tutorial mercy, it was “blubbered” out what a stake was depending on his decision, and that not only was the North Pole hopelessly lost for ever, but that worse might follow. Blackstone was a good soul at heart, and I recal his walking up and down the room in sincere distress as he listened to the sad story. He was a conscientious man, and when he began, “You see what you are coming to, by the course of systematic idleness you have entered on,” and when, too, he began to give warnings of the danger of such a course, with an indistinct allusion to the gallows, it was plain there was hope. After a good deal of sarcasm and anger, and even abuse, I recal his sitting down with his penknife and neatly — he did everything neatly — scratching out the dreadful “malè.” But his conscience would only suffer him to substitute a “vix medi,” a description which, in truth, did not differ much, but which had not the naked horror of the other. I could have embraced his knees. And yet suspicion was excited by this erasure, most unjustly, and but little faith was put in the protestations of the accused; for his eagerness to be present at the show was known, and he was only cleared by the friendly testimony of an expert as to handwriting.

That North Pole was very delightful. It seems to me now to be mostly ships in various positions, and very “spiky” icebergs. The daring navigators, Captain Back and others, always appeared in full uniform. They had all our sympathy. The most exciting scene was the capture of the whale, as it was called, though it scarcely amounted to a capture. When the finny monster had struck out with his tail and sent the boat and crew all into the air, a dreadful spectacle of terror and confusion, which caused a sensation among the audience, exhibited by rustling and motion in the dark, an unpleasantness, however, quickly removed by the humour of our lecturer, who, in his comic way, says, “As this is a process which happens on an average about once in the week, the sailors get quite accustomed to this ducking, and consider it rather fun than otherwise, as it saves them the trouble of taking a bath.” This drollery convulses us, and the youthful mind thinks what it would give to have such wit. Not less delightful was the scene where the seals were playing together on the vast and snowy-white shore, with the great “hicebergs” (so our lecturer had a tendency to phrase it) in the distance, and the two ships all frozen up. We had music all through, as the canvas moved on. And when our lecturer dwelt on the maternal affection of the wounded seal which was struggling to save its offspring, and declined to escape into the water, Mr. George Harker, the admired tenor (but invisible behind the green baize), gave us, with great feeling and effect — was it the ballad of “Let me kiss him for his Mother”?

Only a few years ago, when the intrepid navigators, M’Clintock and others, were exciting public attention, a new panorama of their perils and wanderings was brought out. Faithful to the old loves of childhood, I repaired to the show; but presently begun to rub my eyes. It seemed like an old dream coming back. The boat in the air, the wounded seal, and the navigators themselves, in full uniform, treating with the Esquimaux — all this was familiar. But I rather resented the pointing out of the chief navigator “in the foreground” as the intrepid Sir Leopold, for he was the very one who had been pointed to as the intrepid Captain Back.

Not less welcome in these old days was the ingenious representation of Mr. Green the intrepid aeronaut’s voyage in his great balloon “Nas sau.” There was a dramatic air about all that. The view of gardens, crowded with spectators in very bright dresses (illuminated from behind), and with faces all expressive of delight and wonder, and the balloon in the middle — a practicable balloon, not attached to the canvas. We could see it swaying as the men strove to hold it. I remember the describer’s words to this hour: “At last, all being now ready, Mr. Green, the intrepid aeronaut, and his companion entered the car, and having taken farewell of his friends, gave the signal to cast off, and in a moment the balloon rapidly ascended.” At the same time cheerful music behind the baize, “The Roast Beef of Old England,” I think, struck up, and the garden, wondering spectators, trees, all went down rapidly, the balloon remaining stationary. The effect was most ingeniously produced. I never shall forget the interest with which that voyage was followed. We had the clouds, the stars, the darkened welkin, all moving slowly by (to music). The crossing of the Channel by night, and the rising of the sun — wonderful effect! Plenty of rich fiery streaking well laid on. Then the Continent, and terra firma again; and how ingeniously was a difficulty got rid of. Necessarily, the countries we were to see from Mr. Green’s car could only be under faint bird’s- eye condition, and “so many thousand feet above the level of the sea,” which would make everything rather indistinct and unsatisfactory. We therefore took advantage of the interval between the first and second parts to get rid of our large balloon which blocked up the centre of the canvas, and changed it for a tiny one, which was put away high in the air, in its proper place, where it took up no room, and did quite as well as the other. However, at the close of the performance, when we had travelled over every- thing, and wished to see Mr. Green coining down, we took back our large balloon, and were very glad to see it again, and the wondering faces of the Germans.

There is one scene which the dioramic world seems inclined not willingly to let die. At least it somehow thrusts itself without any regard to decent dioramic fitness upon every kind of diorama indiscriminately. Any student will know at once that I allude to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. This seems to have a sort of fascination for the painters. I never knew a single show that had not this church “lugged in” head and shoulders, or rather porch and pillars, either at the beginning or at the end. I am afraid this is from no spirit of piety or veneration, but simply from the favourable opening the church presents for changing from a daylight view to a gorgeous “night effect.” They know, too, that the good are among the audience in strong force, and that is touching the true chord. We know by heart the clumpy Byzantine pillars and the Moorish arches, and the stairs down to the right, and the round globes of white light lamps burning, and the men in turbans kneeling.

Suddenly we hear the harmonium behind, and the voices of Mr. George Harker, the admired tenor, and Miss Edith Williams, the (also) admired soprano, attuning their admired voices together in a very slow hymn; and gradually the whole changes to midnight, with a crypt lit up with countless lamps and countless worshippers. A dazing and dazzling spectacle, the umbrellas of the good and pious becoming deafening in their approbation. Taken as an old friend, that I have seen in every town in the kingdom, I have an affection for this crypt and its transformation; but still I know every stone in it by heart. Where was it that I saw the DIORAMA OF IRELAND, with “national harps and altars,” “national songs and watchwords,” “national dances and measures,” all in great green letters, made out of staggering round towers and ruined abbeys? — appropriate songs and dances by Miss Biddy Magrath. Where but is an Irish town rather towards the north. I recal the lecturer, a very solemn man, who preached a good deal as the canvas moved on to music — it is a law that canvas can only move to music; and a city with bridges, &c., and a river would slowly pass on, and stop short when it was finally developed. Our lecturer would say, sadly, as if he were breaking a death, “LIM-ER-ICK! the city of the vier-lated te-reaty!” The result of this announcement in the northern town was a burst of hisses, with a counter-demonstration from the back benches. The grand scene, however, was when a bright and gay town came on, and was introduced as “DERRY, THE MAIDEN CITY!” Then there was terrific applause, and even cheers, with a counter-demonstration from the back. It will be conceived that this state of things did not conduce at all to the success of the diorama, and it was very shortly withdrawn from its native land, and exhibited to more indifferent spectators. And yet Miss Magrath’s exertions, both in singing and dancing, were exceedingly arch, and deserved a better fate.

The lecturers are always delightful. What were they — I always think while waiting for the green baize to be drawn — before they took to this profession? Is it a lucrative profession? — by the way, it certainly must be a limited one. How he must get at last absolutely to loathe the thing he described, and yet he always looks at it as he speaks with an air of affection; but in his heart of hearts he must loathe it, or be dead to all human feelings and repugnances. For only consider the “day performance” at two — the night one at eight. Yet he always seems to deliver it with an air of novelty, and an air of wisdom, too, and morality, which is not of the pulpit, or forum, but simply dioramic. It is only when he descends to jests and joking that he loses our respect. A little story of his goes an immense way, especially anything touching on love or courtship. “There,” he says, speaking of the prairies, “the vast rolling plains are covered with a rank lugsurious and rich verjoor. There we can see the solitary wigwam, with the squaw preparing the family kettle, unencumbered by their babies. They have an excellent way in the prairies of dealing with troublesome appendages. Every child is made up into a sort of case or bandage, as depicted in the foreground of the scene. When they are busy, they simply hang them on a tree to be out of the way.” Every father and mother laughs heartily, and with delight, at this humorous stroke. Perhaps the pleasantest of the whole round was a certain diorama that called itself “The Grand Tour,” and which carried out the little fiction of its visitors being “excursionists,” and taken over every leading city on the Continent. We were supposed to take our tickets, “first-class,” at London- bridge, embarked in a practicable steamer at St. Katharine’s Wharf, with its rigging all neatly cut out, so that, as we began to move—or rather, as the many thousand square feet of canvas began to move — we saw the Tower of London, and various objects of interest along the river passing us by. The steamer was uncommonly good indeed, and actually gave delicate people present quite an uncomfortable feeling. Presently all the objects of interest had gone by, and we were out at sea, with fine effects by moonlight, fine effects by blood-red sunrise, and then we were landed, and saw every city that was worth visiting. Against one little “effect” some of our “excursionists” — among the more elderly — made indignant protest. When we were passing through Switzerland and came to Chamounix, where there had been a prodigal expenditure of white paint and a great saving in other colours, and found ourselves at the foot of the great mountain — I forget how many thousand feet above the level of the sea, but we were told to a fraction our lecturer warmed into enthusiasm, and burst out into the lines:

Mont Blanc, the monarch of mountains,

In his robe of snow, &c.

But the greatest danger that menaces us is what our lecturer calls the “have-a-launch,” which must be a very serious thing indeed. “Often ‘ole villages may be reposing in peaceful tranquilhity, the in’abitants fast locked in slumber, when suddenly, without a note of preparation” —- Exactly, that is what such of us as have nerves object to — a startling crash produced behind the baize — a scream among the audience — and the smiling village before us is buried in a mass of snow—white paint. It is the “have-a-launch.” This is the grand coup of the whole. Why does the music take the shape of the mournful Dead March in Saul?

Yet even dioramas have the elements of decay. Sometimes they light on a dull and indifferent town, and get involved in debt and difficulty. The excursions can’t pay their own expenses. I once saw a diorama of the Susquehanna, covering many thousand square feet of canvas, and showing the whole progress of that noble river, sold actually for no more than five pounds. I was strongly tempted, as the biddings rested at that figure. It would be something to say you had bought a panorama once in your life.

Comments: Charles Dickens (1812-1870) was a British novelist and journalist. All the Year Round was a literary periodical that Dickens founded and initially edited, as well as contributing material. Although the piece was written in 1867, Dickens is mostly recalling shows from the 1830s. Moving panoramas (or moving dioramas) of the kind described by Dickens combined panoramic paintings that scrolled pass the viewer with lighting effects and music. Among the panoramas to which he refers are David Roberts’ Moving Diorama of the Polar Expedition (1829) and Aeronautikon! or, Journey of the Great Balloon, originally created in 1836 by panorama specialist the Grieve family and inspired by a balloon flight from Britain to Germany undertaken by Charles Green. These particular panoramas, and Dickens’s commentary, are discussed in Erkki Huhtamo’s book Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles (2013).

Links: Copy at Dickens Journals Online