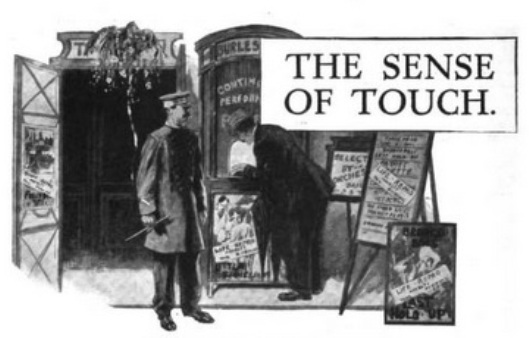

Source: ‘Ole Luke-Oie’ [Ernest Dunlop Swinton], extract from ‘The Sense of Touch’, The Strand Magazine, December 1912, pp. 620-631. Illustrations by John Cameron.

Text: ‘Pon my word, I really don’t know what made me go into the place. I’ve never been keen on cinemas. The ones I went to when they first came out quite choked me off. The jiggling of the pictures pulled my eyes out till they felt like a crab’s, and the potted atmosphere made my head ache. I was strolling along, rather bored with things in general and more than a bit tired, and happened to stop as I passed the doors. It seemed just the ordinary picture palace or electric theatre show – ivory-enamelled portico, neuralgic blaze of flame arc-lights above, and underneath, in coloured incandescents, the words, “Mountains of Fun.”

Fun! Good Lord!

An out-sized and over-uniformed tout, in dirty white gloves and a swagger stick, was strolling backwards and forwards, alternately shouting invitations to see the “continuous performance” and chasing away the recurring clusters of eager-eyed children, whose outward appearance was not suggestive of the possession of the necessary entrance fee. There were highly-coloured posters on every available foot of wall-space – sensational scenes, in which cowboys, revolvers, and assorted deaths predominated – and across them were pasted strips of paper bearing the legend, ” LIFE-REPRO Novelty This Evening.”

I confess that, old as I am, it was that expression which caught me – ” LIFE-REPRO.” It sounded like a new metal polish or an ointment for “swellings on the leg,” but it had the true showman’s ring. I asked the janitor what it meant. Of course he did not know – poor devil! – and only repeated his stock piece: “Splendid new novelty. Now showing. No waiting. Continuous performance. Walk right in.”

I was curious; it was just beginning to rain; and I decided to waste half an hour. No sooner had the metal disc – shot out at me in exchange for sixpence – rattled on to the zinc counter of the ticket-window than the uniformed scoundrel thrust a handbill on me and almost shoved me through a curtained doorway. Quite suddenly I found myself in a dark room, the gloom of which was only accentuated by the picture quivering on a screen about fifty feet away. The change from the glare outside was confusing and the atmosphere smote me, and as I heard the door bang and the curtain being redrawn I felt half inclined to turn round and go out. But while I hesitated, not daring to move until my eyes got acclimatized, someone flashed an electric torch in my eyes, grabbed my ticket, and squeaked, ” Straight along, please,” then switched off the light.

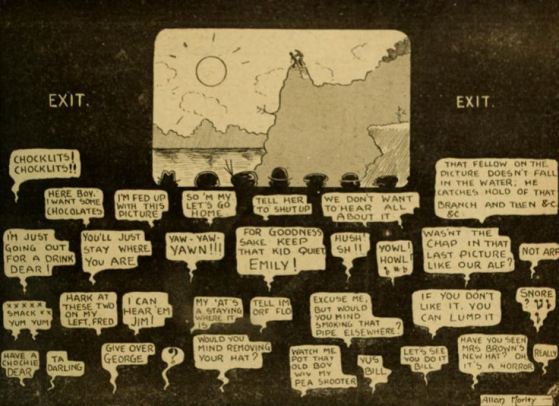

Useful, wasn’t it? I couldn’t see an inch. You know, I’m not very touchy as a rule, but I was getting a bit nettled, and a good deal of my boredom had vanished. I groped my way carefully down what felt like an inclined gangway, now in total darkness, for there was at the moment no picture on the screen, and at once stumbled down a step. A step, mind you, in the centre of a gangway, in a place of entertainment which is usually dark! I naturally threw out my hands to save myself and grabbed what I could. There was a scream, and the film then starting again, I discovered that I was clutching a lady by the hair. The whole thing gave me a jar and threw me into a perspiration – you must remember I was still shaky after my illness. When, as I was apologizing, the same, or another, fool with the torchlight flashed it at my waistcoat and said, “Mind the step,” I’m afraid I told him, as man to man, what I thought of him and the whole beastly show. I was now really annoyed, and showed it. I had no notion there were so many people in the hall until I heard the cries of “Ssshh! ” “Turn him out! ” from all directions.

When I was finally led to a flap-up seat – which I nearly missed, by the way, in the dark – I discovered the reason for the impatience evinced by the audience. I had butted in with my clatter and winged words at the critical moment of a touching scene. To the sound of soft, sad music, all on the black notes, the little incurable cripple child in the tenement house was just being restored to health by watching the remarkably quick growth of the cowslips given to her by the kind-hearted scavenger. Completely as boredom had been banished by the manner of my entrée it quickly returned while I suffered the long-drawn convalescence of ” Little Emmeline.” As soon as this harrowing film was over and the lights were raised I took my chance of looking round.

The hall was very much the usual sort of place – perhaps a bit smaller than most – long and narrow, with a floor sloping down from the back. In front of the screen, which was a very large one, was an enclosed pit containing some artificial palms and tin hydrangeas, a piano and a harmonium, and in the end wall at its right was a small door marked ” Private.” In the side wall on the left near the proscenium place was an exit. The only other means of egress, as far as I could see, was the doorway through which I had entered. Both of these were marked by illuminated glass signs, and on the walls were notices of “No smoking,” “The management beg to thank, those ladies who have so kindly removed their hats,” and advertisement placards – mostly of chocolate. The decorations were too garish for the place to be exactly homely, but it was distinctly commonplace, a contrast to the shambles it became later on. What?

Yes! I daresay you know all about these picture palaces, but I’ve got to give you the points as they appealed to me. I’m not telling you a story, man. I’m simply trying to give you an exact account of what happened. It’s the only way I can do it.

The ventilation was execrable, in spite of the couple of exhaust fans buzzing round overhead, and the air hung stagnant and heavy with traces of stale scent, while wafts of peppermint, aniseed, and eucalyptus occasionally reached me from the seats in front. Tobacco smoke might have increased the density of the atmosphere, but it would have been a welcome cloak to some of the other odours. The place was fairly well filled, the audience consisting largely of women and children of the poorer classes – even babies in arms – just the sort of innocent holiday crowd that awful things always happen to.

By the time I had noticed this much the lights were lowered, and we were treated to a scene of war which converted my boredom into absolute depression. I must describe it to you, because you always will maintain that we are a military nation at heart. By Jove, we are! Even the attendants at this one-horse gaff were wearing uniforms. And the applause with which the jumble of sheer military impossibility and misplaced sentiment presented to us was greeted proves it. The story was called “Only a Bugler Boy.” The first scene represented a small detachment of British soldiers ” At the Front” on ” Active Service” in a savage country. News came in of the “foe.” This was the occasion for a perfect orgy of mouthing, gesticulation, and salutation. How they saluted each other, usually with the wrong hand, without head-covering, and at what speed ! The actors were so keen to convey the military atmosphere that the officers, as often as not, acknowledged a salute before it was given.

Alter much consultation, deep breathing exercise, and making of goo-goo eyes, the long-haired rabbit who was in command selected a position for “defence to the death” so obviously unsuitable and suicidal that he should have been ham-strung at once by his round-shouldered gang of supers. But, no! In striking attitudes they waited to be attacked at immense and quite unnecessary disadvantage by the savage horde. Then, amid noise and smoke, the commander endeavoured to atone for the hopeless situation in which he had placed his luckless men by waving his sword and exposing himself to the enemy’s bullets. I say “atone,” for it would have been the only chance for his detachment if he had been killed, and killed quickly. Well, after some time and many casualties, it occurred to him that it would be as well to do something he should have done at first, and let the nearest friendly force know of his predicament. The diminutive bugler with the clean face and nicely-brushed hair was naturally chosen for this very dangerous mission, which even a grown man would have had a poor chance of carrying out, and after shaking hands all round, well in the open, the little hero started off with his written message.

Then followed a prolonged nightmare of crawling through the bush-studded desert.

Bugler stalled savage foe, and shot several with his revolver. Savage foe stalked bugler and wounded him in both arms and one leg. Finally, after squirming in accentuated and obvious agony for miles, bugler reached the nearest friendly force, staggered up to its commander, thrust his despatch upon him, and swooned in his arms. Occasion for more saluting, deep breathing, and gesticulation, and much keen gazing through field-glasses – notwithstanding the fact that if the beleaguered garrison were in sight the sound of the firing must have been heard long before ! Then a trumpet-call on the harmonium, and away dashed the relief force of mounted men.

Meanwhile we were given a chance of seeing how badly things had been going with the devoted garrison at bay. It was only when they were at their last gasp and cartridge that the relief reached them. With waving of helmets and cheers from the defenders, the first two men of the relieving force hurled themselves over the improvised stockade. You know what they were? I knew what they must be long before they appeared. And it is hardly necessary to specify to which branches of His Majesty’s United Services they belonged. The sorely-wounded but miraculously tough bugler took the stockade in his stride a very good third. He had apparently recovered sufficiently to gallop all the way back with the rescuers – only to faint again, this time in the arms of his own commanding officer. Curtain! “They all love Jack,” an imitation of bagpipes on the harmonium, and “Rule Britannia” from the combined orchestra. As I say, this effort of realism was received with great applause, even by the men present.

As soon as the light went up I had a look at my neighbours. The seats on each side of me were empty, and in the row in front, about a couple of seats to my right, there was one occupant. He was a young fellow of the type of which one sees only too many in our large towns – one of the products of an overdone industrialism. He was round-shouldered and narrow-chested, and his pale thin face suggested hard work carried out in insanitary surroundings and on unwholesome food. His expression was precocious, but the loose mouth showed that its owner was far too unintelligent to be more than feebly and unsuccessfully vicious. He wore a yachting cap well on the back of his head, and on it he sported a plush swallow or eagle – or some other bird – of that virulent but non-committal blue which is neither Oxford nor Cambridge. It was Boat-Race week. He was evidently out for pleasure – poor devil! – and from his incidental remarks, which were all of a quasi-sporting nature, I gathered that he was getting it. I felt sorry for him and sympathized in his entire absorption in the strange scenes passing before his eyes – scenes of excitement and adventure far removed from the monotonous round of his squalid life. How much better an hour of such innocent amusement than time and money wasted in some boozing-ken – eh?

Well, I’m not quite sure what it means myself – some sort of a low drinking-den. But, anyway, that’s what I felt about it. After all, he was a harmless sort of chap, and his unsophisticated enjoyment made me envious. I took an interest in him – thought of giving him a bob or two when I went out. I want you to realize that I had nothing but kindly feelings towards the fellow. He comes in later on – wasn’t so unsuccessful after all.

Then we had one of those interminable scenes of chase in which a horseman flies for life towards you over endless stretches of plain and down the perspective of long vistas of forest, pursued at a discreet distance by other riders, who follow in his exact tracks, even to avoiding the same tree-stumps, all mounted on a breed of horse which does forty-five miles an hour across country and fifty along the hard high road. I forget the cause of the pursuit and its ending, but I know revolvers were used.

The next film was French, and of the snowball type. A man runs down a street. He is at once chased by two policemen, one long and thin and the other fat and bow-legged with an obviously false stomach. The followers very rapidly increase in number to a mixed mob of fifty or more, including nurses with children in perambulators. They go round many corners, and round every corner there happens to be a carefully arranged obstacle which they all fall over in a kicking heap. I remember that soot and whitewash played an important part, also that the wheels of the passing vehicles went round the wrong way.

Owing to the interruption of light, was it? I daresay. Anyway, it was very annoying. Then we had a bit of the supernatural. I’m afraid I didn’t notice what took place, so I’ll spare you a description. I was entirely engrossed with the efforts of the wretched pianist to play tremolo for ten solid minutes. I think it was the ghost melody from “The Corsican Brothers ” that she was struggling with, and the harmonium did not help one bit. The execution got slower and slower and more staccato as her hands grew tired, and at the end I am sure she was jabbing the notes with her aching fingers straight and stiff. Poor girl! What a life!

At about this moment, as far as I remember, a lady came in and took the seat in front of mine. She was a small woman, and was wearing a microscopic bonnet composed of two strings and a sort of crepe muffin. The expression of her face was the most perfect crystallization of peevishness I’ve ever seen, and her hair was screwed up into a tight knob about the size and shape of a large snail-shell. Evidently not well off – probably a charwoman. I caught a glimpse of her gloves as she loosened her bonnet-strings, and the fingertips were like the split buds of a black fuchsia just about to bloom. Shortly after she had taken her seat my friend with the Boat-Race favour suddenly felt hungry, cracked a nut between his teeth, spat out the shell noisily, and ate the kernel with undisguised relish. The lady gathered her mantle round her and sniffed. I was not surprised. The brute continued to crack nuts, eject shells, and chew till he killed all my sympathy for him, till I began to loathe his unhealthy face, and longed for something to strike him dead. This was absolutely the limit, and I should have cleared out had not the words LIFE-REPRO” on the handbill caught my eye. After all it must come to that soon, and I determined to sit the thing out. After one or two more films of a banal nature there was a special interval – called “Intermission” on the screen – and signs were not wanting of the approach of the main event of the show.

Two of the youths had exchanged their electric torches for trays, and perambulated the gangways with cries of “Chuglit— milk chuglit.” A third produced a large garden syringe and proceeded to squirt a fine spray into the air. This hung about in a cloud, and made the room smell like a soap factory. When the curtain bell sounded the curtain was not drawn nor were the lights lowered. A man stepped out of the small door and climbed up on to the narrow ledge in front of the screen, which served as a kind of stage or platform, and much to my disgust made obvious preparation to address the audience. He was a bulky fellow, and his apparent solidity was increased by the cut of his coat. His square chin added to the sense of power conveyed by his build, while a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles gave him an air of seriousness and wisdom. I at once sized him up as a mountebank, and thought I knew what sort of showman’s patter to expect. He did not waste much time before he got busy. Looking slowly all round the room, he fixed my sporting friend with a baleful glare until the latter stopped eating, then cleared his throat and began …

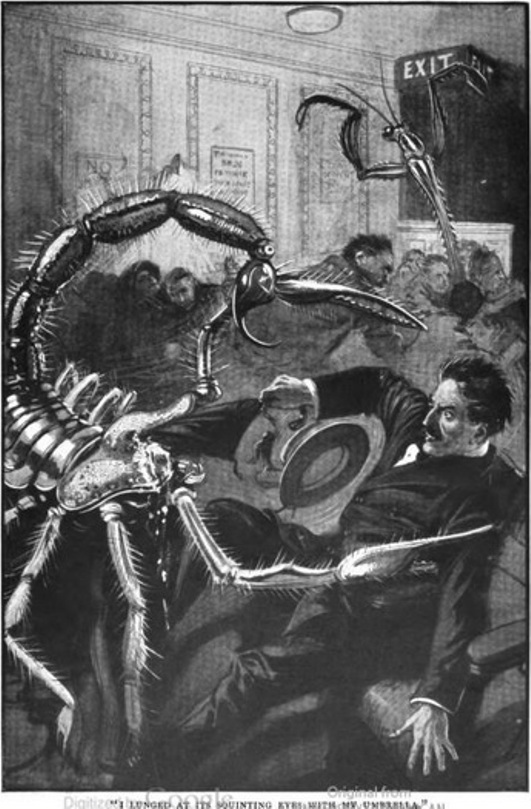

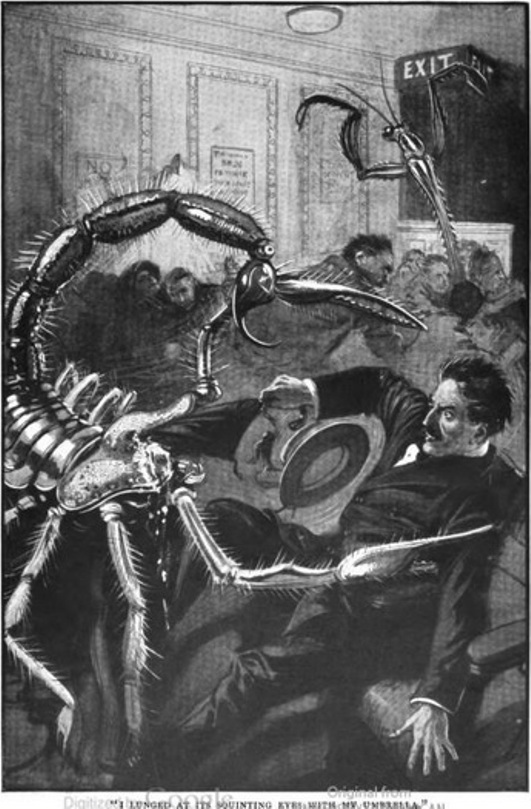

Comments: Ernest Dunlop Swinton (1868-1951) was a British military officer (influential in the development of tanks in the First World War) and a writer, producing fiction under the pseudonym O’le Luk-Oie. The story continues with an announcer promising a natural history film of unsurpassed life-like realism. The film shows a praying mantis and a scorpion which come out of the screen giant-sized and attack the audience, killing those that the narrator disliked before turning on him (see illustration below). In the end it turns out to have been a dream. The description of a cinema show, though sardonic, is filled with useful documentary detail. The garden syringe is a reference to the disinfectant sprays commonly used on cinema audiences at this time.

Links: Copy of the complete story on the Internet Archive