Source: H.G. Wells, ‘Mr. Wells Reviews a Current Film: He Takes Issue With This German Conception of What The City of One Hundred Years Hence Will Be Like’, New York Times, 17 April 1927, p. 4

Text: I have recently seen the silliest film.

I do not believe it would be possible to make one sillier.

And as this film sets out to display the way the world is going, I think The Way the World is Going may very well concern itself with this film.

It is called Metropolis, it comes from the great Ufa studios in Germany, and the public is given to understand that it has been produced at enormous cost.

It gives in one eddying concentration almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own.

It is a German film and there have been some amazingly good German films, before they began to cultivate bad work under cover of a protective quota. And this film has been adapted to the Anglo-Saxon taste, and quite possibly it has suffered in the process, but even when every allowance has been made for that, there remains enough to convince the intelligent observer that most of its silliness must be fundamental.

Possibly I dislike this soupy whirlpool none the less because I find decaying fragments of my own juvenile work of thirty years ago, The Sleeper Awakes, floating about in it.

Capek’s Robots have been lifted without apology, and that soulless mechanical monster of Mary Shelley’s, who has fathered so many German inventions, breeds once more in this confusion.

Originality there is none. Independent thought, none.

Where nobody has imagined for them the authors have simply fallen back on contemporary things.

The aeroplanes that wander about above the great city show no advance on contemporary types, though all that stuff could have been livened up immensely with a few helicopters and vertical or unexpected movements.

The motor cars are 1926 models or earlier. I do not think there is a single new idea, a single instance of artistic creation or even intelligent anticipation, from first to last in the whole pretentious stew; I may have missed some point of novelty, but I doubt it; and this, though it must bore the intelligent man in the audience, makes the film all the more convenient as a gauge of the circle of ideas, the mentality, from which it has proceeded.

The word Metropolis, says the advertisement in English, ‘is in itself symbolic of greatness’- which only shows us how wise it is to consult a dictionary before making assertions about the meaning of words.

Probably it was the adapter who made that shot. The German ‘Neubabelsburg’ was better, and could have been rendered ‘New Babel’. It is a city, we are told, of ‘about one hundred years hence.’ It is represented as being enormously high; and all the air and happiness are above and the workers live, as the servile toilers in the blue uniform in The Sleeper Awakes lived, down, down, down below.

Now far away in the dear old 1897 it may have been excusable to symbolize social relations in this way, but that was thirty years ago, and a lot of thinking and some experience intervene.

That vertical city of the future we know now is, to put it mildly, highly improbable. Even in New York and Chicago, where the pressure on the central sites is exceptionally great, it is only the central office and entertainment region that soars and excavates. And the same centripetal pressure that leads to the utmost exploitation of site values at the centre leads also to the driving out of industrialism and labour from the population center to cheaper areas, and of residential life to more open and airy surroundings. That was all discussed and written about before 1900. Somewhere about 1930 the geniuses of Ufa studios will come up to a book of Anticipations which was written more than a quarter of a century ago. The British census returns of 1901 proved clearly that city populations were becoming centrifugal, and that every increase in horizontal traffic facilities produced a further distribution. This vertical social stratification is stale old stuff. So far from being ‘a hundred years hence,’ Metropolis, in its forms and shapes, is already, as a possibility, a third of a century out of date.

But its form is the least part of its staleness. This great city is supposed to be evoked by a single dominating personality. The English version calls him John Masterman, so that there may be no mistake about his quality. Very unwisely he has called his son Eric, instead of sticking to good hard John, and so relaxed the strain. He works with an inventor, one Rotwang, and they make machines. There are a certain number of other people, and the ‘sons of the rich’ are seen disporting themselves, with underclad ladies in a sort of joy conservatory, rather like the ‘winter garden’ of an enterprising 1890 hotel during an orgy. The rest of the population is in a state of abject slavery, working in ‘shifts’ of ten hours in some mysteriously divided twenty-four hours, and with no money to spend or property or freedom. The machines make wealth. How, is not stated. We are shown rows of motor cars all exactly alike; but the workers cannot own these, and no ‘sons of the rich’ would. Even the middle classes nowadays want a car with personality. Probably Masterman makes these cars in endless series to amuse himself.

One is asked to believe that these machines are engaged quite furiously in the mass production of nothing that is ever used, and that Masterman grows richer and richer in the process. This is the essential nonsense of it all. Unless the mass of the population has the spending power there is no possibility of wealth in a mechanical civilization. A vast, penniless slave population may be necessary for wealth where there are no mass production machines, but it is preposterous with mass production machines. You find such a real proletariat in China still; it existed in the great cities of the ancient world; but you do not find it in America, which has gone furtherest in the direction of mechanical industry, and there is no grain of reason in supposing it will exist in the future. Masterman’s watchword is ‘Efficiency,’ and you are given to understand it is a very dreadful word, and the contrivers of this idiotic spectacle are so hopelessly ignorant of all the work that has been done upon industrial efficiency that they represent him as working his machine-minders to the point of exhaustion, so that they faint and machines explode and people are scalded to death. You get machine-minders in torment turning levers in response to signals – work that could be done far more effectively by automata. Much stress is laid on the fact that the workers are spiritless, hopeless drudges, working reluctantly and mechanically. But a mechanical civilization has no use for mere drudges; the more efficient its machinery the less need there is for the quasi-mechanical minder. It is the inefficient factory that needs slaves; the ill-organized mine that kills men. The hopeless drudge stage of human labour lies behind us. With a sort of malignant stupidity this film contradicts these facts.

The current tendency of economic life is to oust the mere drudge altogether, to replace much highly skilled manual work by exquisite machinery in skilled hands, and to increase the relative proportion of semi-skilled, moderately versatile and fairly comfortable workers. It may indeed create temporary masses of unemployed, and in The Sleeper Awakes there was a mass of unemployed people under the hatches. That was written in 1897, when the possibility of restraining the growth of large masses of population had scarcely dawned on the world. It was reasonable then to anticipate an embarrassing underworld of under-productive people. We did not know what to do with the abyss. But there is no excuse for that today. And what this film anticipates is not unemployment, but drudge employment, which is precisely what is passing away. Its fabricators have not even realized that the machine ousts the drudge.

‘Efficiency’ means large-scale productions, machinery as fully developed as possible, and high wages. The British Government delegation sent to study success in America has reported unanimously to that effect. The increasingly efficient industrialism of America has so little need of drudges that it has set up the severest barriers against the flooding of the United States by drudge immigration. ‘Ufa’ knows nothing of such facts.

A young woman appears from nowhere in particular to ‘help’ these drudges; she impinges upon Masterman’s son Eric, and they go to the ‘Catacombs,’ which, in spite of the gas mains, steam mains, cables, and drainage, have somehow contrived to get over from Rome, skeletons and all, and burrow under this city of Metropolis. She conducts a sort of Christian worship in these unaccountable caverns, and the drudges love and trust her. With a nice sense of fitness she lights herself about the Catacombs with a torch instead of the electric lamps that are now so common.

That reversion to torches is quite typical of the spirit of this show. Torches are Christian, we are asked to suppose; torches are human. Torches have hearts. But electric hand-lamps are wicked, mechanical, heartless things. The bad, bad inventor uses quite a big one. Mary’s services are unsectarian, rather like afternoon Sunday-school, and in her special catacomb she has not so much an altar as a kind of umbrella-stand full of crosses. The leading idea of her religion seems to be a disapproval of machinery and efficiency. She enforces the great moral lesson that the bolder and stouter human effort becomes, the more spiteful Heaven grows, by reciting the story of Babel. The story of Babel, as we know, is a lesson against ‘Pride.’ It teaches the human soul to grovel. It inculcates the duty of incompetence. The Tower of Babel was built, it seems, by bald-headed men. I said there was no original touch in the film, but this last seems to be a real invention. You see the bald-headed men building Babel. Myriads of them. Why they are bald is inexplicable. It is not even meant to be funny, and it isn’t funny; it is just another touch of silliness. The workers in Metropolis are not to rebel or do anything for themselves, she teaches, because they may rely on the vindictiveness of Heaven.

But Rotwang, the inventor, is making a Robot, apparently without any license from Capek, the original patentee. It is to look and work like a human being, but it is to have no ‘soul.’ It is to be a substitute for drudge labour. Masterman very properly suggests that it should never have a soul, and for the life of me I cannot see why it should. The whole aim of mechanical civilization is to eliminate the drudge and the drudge soul. But this is evidently regarded as very dreadful and impressive by the producers, who are all on the side of soul and love and suchlike. I am surprised they do not pine for souls in the alarm clocks and runabouts. Masterman, still unwilling to leave bad alone, persuades Rotwang to make this Robot in the likeness of Mary, so that it may raise an insurrection among the workers to destroy the machines by which they live, and so learn that it is necessary to work. Rather intricate that, but Masterman, you understand, is a rare devil of a man. Full of pride and efficiency and modernity – all those horrid things.

Then comes the crowning absurdity of the film, the conversion of the Robot into the likeness of Mary. Rotwang, you must understand, occupies a small old house, embedded in the modern city, richly adorned with pentagrams and other reminders of the antiquated German romances out of which its owner has been taken. A quaint smell of Mephistopheles is perceptible for a time. So even at Ufa, Germany can still be dear old magic-loving Germany. Perhaps Germans will never get right away from the Brocken. Walpurgis Night is the name-day of the German poetic imagination, and the national fantasy capers insecurely for ever with a broomstick between its legs. By some no doubt abominable means Rotwang has squeezed a vast and well-equipped modern laboratory into this little house. It is ever so much bigger than the house, but no doubt he has fallen back on Einstein and other modern bedevilments. Mary has to be trapped, put into a machine like a translucent cocktail shaker, and undergo all sorts of pyrotechnic treatment in order that her likeness may be transferred to the Robot. The possibility of Rotwang just simply making a Robot like her, evidently never entered the gifted producer’s head. The Robot is enveloped in wavering haloes, the premises seem to be struck by lightning repeatedly, the contents of a number of flasks and carboys are violently agitated, there are minor explosions and discharges. Rotwang conducts the operations with a manifest lack of assurance, and finally, to his evident relief, the likeness is taken and things calm down. The false Mary then winks darkly at the audience and sails off to raise the workers. And so forth and so on. There is some rather good swishing about in water, after the best film traditions, some violent and unconvincing machine-breaking and rioting and wreckage, and then, rather confusedly, one gathers that Masterman has learnt a lesson, and that workers and employers are now to be reconciled by ‘Love.’

Never for a moment does one believe any of this foolish story; for a moment is there anything amusing or convincing in its dreary series of strained events. It is immensely and strangely dull. It is not even to be laughed at. There is not one good-looking nor sympathetic nor funny personality in the cast; there is, indeed, no scope at all for looking well or acting like a rational creature amid these mindless, imitative absurdities. The film’s air of having something grave and wonderful to say is transparent pretence. It has nothing to do with any social or moral issue before the world or with any that can ever conceivably arise. It is bunkum and poor and thin even as bunkum. I am astonished at the toleration shown it by quite a number of film critics on both sides of the Atlantic. And it costs, says the London Times, six million marks! How they spent all that upon it I cannot imagine. Most of the effects could have been got with models at no great expense.

The pity of it is that this unimaginative, incoherent, sentimentalizing, and make-believe film, wastes some very fine possibilities. My belief in German enterprise has had a shock. I am dismayed by the intellectual laziness it betrays. I thought Germans even at the worst could toil. I thought they had resolved to be industriously modern. It is profoundly interesting to speculate upon the present trend of mechanical inventions and of the reactions of invention upon labour conditions. Instead of plagiarizing from a book thirty years old and resuscitating the banal moralizing of the early Victorian period, it would have been almost as easy, no more costly, and far more interesting to have taken some pains to gather the opinions of a few bright young research students and ambitious, modernizing architects and engineers about the trend of modern invention, and develop these artistically. Any technical school would have been delighted to supply sketches and suggestions for the aviation and transport of A.D. 2027. There are now masses of literature upon the organization of labour for efficiency that could have been boiled down at a very small cost. The question of the development of industrial control, the relation of industrial to political direction, the way all that is going, is of the liveliest current interest. Apparently the people at Ufa did not know of these things and did not want to know about them. They were too dense to see how these things could have been brought into touch with the life of today and made interesting to the man in the street. After the worst traditions of the cinema world, monstrously self-satisfied and self-sufficient, convinced of the power of loud advertisement to put things over with the public, and with no fear of searching criticism in their minds, no consciousness of thought and knowledge beyond their ken, they set to work in their huge studio to produce furlong after furlong of this ignorant, old-fashioned balderdash, and ruin the market for any better film along these lines.

Six million marks! The waste of it!

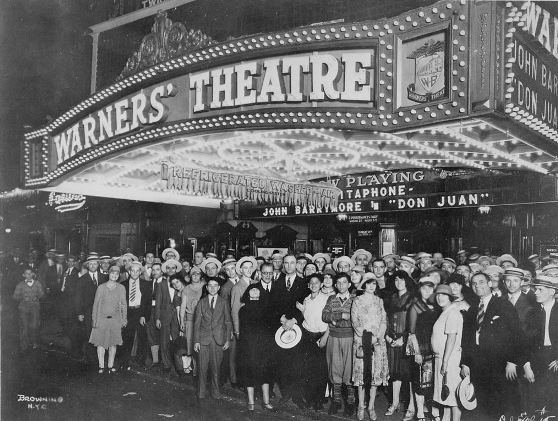

The theatre when I visited it was crowded. All but the highest-priced seats were full, and the gaps in these filled up reluctantly but completely before the great film began. I suppose every one had come to see what the city of a hundred years hence would be like. I suppose there are multitudes of people to be ‘drawn’ by promising to show them what the city of a hundred years hence will be like. It was, I thought, an unresponsive audience, and I heard no comments. I could not tell from their bearing whether they believed that Metropolis was really a possible forecast or no. I do not know whether they thought that the film was hopelessly silly or the future of mankind hopelessly silly. But it must have been one thing or the other.

Comments: Herbert George Wells (1866-1946) was a British novelist, short story writer, historian and social commentator. He is best known for this works of science fiction, of which When the Sleeper Wakes (1898) is close in theme to Metropolis (Germany 1926), so thoughts of plagiarism may have coloured his attack on Fritz Lang’s film. He presumably saw the film in London. The Way the World is Going was a non-fiction work published by Wells in 1928.

Links: Copy at New York Times archives (subscription site)

Transcription at The Time Machine