Source: Ivan Butler, Silent Magic: Rediscovering the Silent Film Era (London: Columbus Books, 1987), pp. 27-31

Text: During the early part of the 1920s my own cinema-going was restricted by the confinements of boarding-school during term time, and in the holidays (to a lesser extent) by the fact that at least in our neighbourhood ‘the pictures’, though tolerated and even enjoyed, were still regarded as a poor and slightly dubious relative of the live theatre, the picture gallery and the concert hall. Their passage towards respectability was not helped by scandals in Hollywood such as the ‘Fatty Arbuckle Affair’. I can still recollect the atmosphere of something sinister and shuddersome that surrounded the very word ‘Arbuckle’ long after the trials (and complete acquittal) of the unfortunate comedian, even though my innocent ideas of what actually took place in that San Francisco apartment during the lively party on 5 September 1921 were wholly vague and inaccurate – if tantalizing. In his massive history of American cinema, The Movies, Richard Griffith writes, “During the course of the First World War the middle class, by imperceptible degrees, became a part of the movie audience.’ ‘lmperceptible’ might be regarded as the operative word. However, when it comes to paying surreptitious visits a great many obstacles can be overcome by a little guile and ingenuity, and I don’t remember feeling particularly deprived in that respect. I managed to see most of what I wanted to see.

Our ‘local’ was the cosy little Royal in Kensington High Street, London – a bus journey away. The Royal has been gone for half a century, its demise hastened by the erection of a super-cinema at the corner of Earl’s Court Road. To the faithful it was known not as the Royal but as the Little Cinema Under the Big Clock in the High Street. The clock itself is gone now, but on a recent visit I though I could spot its former position by brackets that remain fixed high in the brick wall. The entrance to the cinema was through a passageway between two small shops, discreetly hidden except for two frames of stills and a small poster. A pause at the tiny box-office, a turn to the left, a step through a swing door and a red baize curtain, and one was in the enchanted land – not, however, in sight of the screen, because that was flush with the entrance, so you saw a grossly twisted pulsating picture which gradually formed itself into shape as, glancing backwards so as not to miss anything, you groped your way up to your seat. To the right of the screen was the clock in a dim red glow, an indispensable and friendly feature of nearly all cinemas in those days, and a warning – as one was perhaps watching the continuous programme through for the second run, that time was getting on. Prices were modest: from 8d (3p), to 3s (15p). This was fairly general in the smaller halls; cheaper seats were available in some, particularly in the provinces, others – slightly more imposing demanded slightly more for the back rows, possibly with roomier seats and softer upholstery, but such elitism was not, to my memory, practised at the Royal.

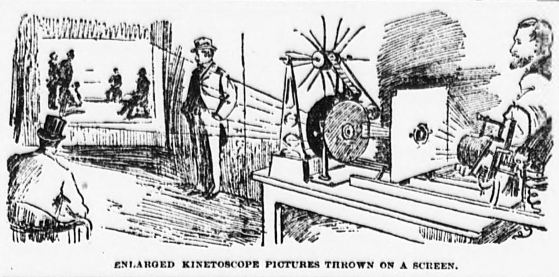

Projection was to our unsophisticated eyes generally good, preserving the often marvellously crisp and well graded black-and-white photography. Programmes were changed twice weekly (but the cinemas were closed on Sundays, at any rate during the early years) and continuous from about 2 o’clock. They consisted as a rule of a newsreel such as the Pathé Gazette with its proudly crowing cockerel (silent, of course), a two-reel comedy (sometimes the best part of the entertainment), Eve’s Film Review, a feminine-angled magazine the high spot of which was the appearance of Felix the Cat walking, and, finally, the feature film. This was before the days when the double-feature programme became general. Somewhere between the items there would be a series of slide advertisements – forerunner of Messrs Pearl and Dean – which always seemed to include a glowing picture of Wincarnis among its local and ‘forthcoming’ attractions. The average moviegoer of those days (much as today, though perhaps to a greater extent) went to see the star of a film rather than the work of its director; Gish rather than Griffith, Bronson more than Brenon, Bow more than Badger, Swanson more than DeMille though as the years went by the names of the directors became more familiar and their importance more fully recognized. Criticism was often surprisingly informed and uncompromising.

Musical accompaniment at the Royal was provided by a piano during the less frequented hours, supplanted by a trio who arrived at a fixed time regardless of what was happening on the screen. I remember well the curious uplift we felt as the three musicians arrived, switched on their desk lights, tuned up and burst into sound, perhaps at a suitable moment in the story, perhaps not. Meanwhile the pianist (always, I recollect, a lady) packed up and left for a well deserved rest and cup of tea. The skill of many of these small cinema groups, even in the most modest conditions, was remarkable; their ability to adapt, week after week, often with two programmes a week and with little or no rehearsal, to events distortedly depicted a few feet before them, was beyond praise. The old joke about William Tell for action, ‘Hearts and Flowers’ for sentiment, the Coriolan overture for suspense and that’s the lot, was an unfair and unfunny gibe.

I have described the old Kensington Royal in some detail as it was fairly typical of modest cinemas everywhere in Britain at that time. Most were at least reasonably comfortable and gave good value for little money, maintaining decent standards of presentation. Very few deserved the derogatory term ‘flea-pit’, though ‘mouse parlour’ might sometimes have been an accurate description. On one occasion the scuttering of mice across the bare boards between the rows of seats rather disturbed my viewing of a W.C. Fields film (Running Wild, I think it was), though the print was so villainously cut and chopped about that the story was difficult to follow in any case. But such cases were infrequent. I have forgotten the name of the cinema, and the town shall remain anonymous.

Sometimes, in early days, films would be shown in old disused churches, and it is supposedly through this that the employment of an organ for accompaniment in larger cinemas became general. The first exponent was probably Thomas L. Talley, who in 1905 built a theatre with organ specifically for the screening of movies in Los Angeles. It was soon discovered that such an organ could be made to do many things an orchestra could not: it could fit music instantaneously to changes of action, and simulate doorbells, whistles, sirens and bird-song, as well as many percussive instruments. On one later make of organ an ingenious device of pre-set keys made available no fewer than thirty-nine effects and even emotions, including Love (three different kinds), Anger, Excitement, Storm, Funeral, Gruesome, ‘Neutral’ (three kinds), and FULL ORGAN. This last effect, with presumably all the above, plus Quietude, Chase, China, Oriental, Children, Happiness, March, Fire, etc. all sounding together, must have been awesome indeed. […] Before long the organ interlude became an important part of any programme, as the grandly ornate and gleaming marvel rose majestically from the depths of the pit in a glowing flood of coloured light.

Nothing, however, could equal the effect of a large orchestra in a major cinema, which could be overwhelming. The accompaniment (of Carl Davis conducting the Thames Silents Orchestra) to the 1983 screening of The Wind, for instance, was a revelation that will never be forgotten by those who had never before ‘heard’ a silent film in all its glory, particularly at the climax of the storm.

Admittedly, at times, particularly from the front seats, the presence of a busy group of players could be distracting; their lights would impinge on the screen, their busy fiddle bows and occasionally bobbing heads would make concentration on what the shadows behind them were up to a little difficult. In general, however, their mere presence, apart from the music, added immeasurably to the sense of occasion and until one got used to it the cold vacancy below the screen in the early days of sound had a chilling effect. Those cinema musicians are surely remembered with warm affection and regard by all of us who were fortunate enough to have heard them.

[…]

In these days of multi-screen conglomerates it is difficult to imagine the awe and excitement that could be aroused by the greatest of the old-style movie palaces; the thick-piled carpets into which our feet sank, the powdered flunkies and scented sirens who took our tickets with a unique mixture of welcoming smile, condescending grace and unwavering dignity, the enormous chandelier-lit entrance halls, the statues, the coloured star portraits, the playing fountains, the rococo kiosks – all leading through cathedral-dim corridors to the dark, perfumed auditorium itself, the holy of holies where we would catch our first glimpse of Larry Semon plastering Fatty Arbuckle with bags of flour.

Prices, of course, were rather grander than in the smaller, humbler houses, roughly (for variations were wide) from about 1s 3d (6p) or 2s 4d (12p) to 8s 6d (43p) or even 11s 6d (57p); but once you had paid your tribute to the box-office every effort was made to see that you felt you were welcome, were getting your money’s worth and were someone of importance – that this whole occasion was especially for you.

Comments: Ivan Butler (1909-1998), after a career as an actor, went on to become a notable writer on the art and history of cinema. His Silent Magic is a particularly evocative memoir of the silent films he could remember when in his eighties. The American comedian Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle was accused of the rape and manslaughter minor actress and model Virginia Rappe. Though acquitted, thanks to lurid reporting his career was ruined. The scandal helped lead to the formation of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America to self-govern the American motion picture industry. The Eve’s Film Review cinemagazine was produced by Pathé, who also made Pathé Gazette. Thames Silents was the name given to a series of theatrical screenings and broadcasts of restored silent films with orchestral scores by Carl Davis, produced by Photoplay Productions and Thames Television over 1980-1990.