Source: Marcel Proust, À la recherche du temps perdu: 1 – Du côté de chez Swann (1913), translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin as Remembrance of Things Past (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983), vol. 1, pp. 9-11

Text: At Combray, as every afternoon ended, long before the time when I should have to go to bed and lie there, unsleeping, far from my mother and grandmother, my bedroom became the fixed point on which my melancholy and anxious thoughts were centred. Someone had indeed had the happy idea of giving me, to distract me on evenings when I seemed abnormally wretched, a magic lantern, which used to be set on top of my lamp while we waited for dinner-time to come; and, after the fashion of the master-builders and glass-painters of gothic days, it substituted for the opaqueness of my walls an impalpable iridescence, supernatural phenomena of many colours, in which legends were depicted as on a shifting and transitory window. But my sorrows were only increased thereby, because this mere change of lighting was enough to destroy the familiar impression I had of my room, thanks to which, save for the torture of having to go to bed, it had become quite endurable. Now I no longer recognised it, and felt uneasy in it, as in a room in some hotel or chalet, in a place where I had just arrived by train for the first time.

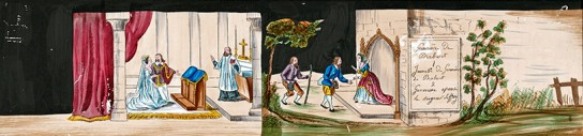

Riding at a jerky trot, Golo, filled with an infamous design, issued from the little triangular forest which dyed dark-green the slope of a convenient hill, and advanced fitfully towards the castle of poor Geneviève de Brabant. This castle was cut off short by a curved line which was in fact the circumference of one of the transparent ovals in the slides which were pushed into position through a slot in the lantern. It was only the wing of a castle, and in front of it stretched a moor on which Geneviève stood lost in contemplation, wearing a blue girdle. The castle and the moor were yellow, but I could tell their colour without waiting to see them, for before the slides made their appearance the old-gold sonorous name of Brabant had given me an unmistakable clue. Golo stopped for a moment and listened sadly to the accompanying patter read aloud by my great-aunt, which he seemed perfectly to understand, for he modified his attitude with a docility not devoid of a degree of majesty, so as to conform to the indications given in the text; then he rode away at the same jerky trot. And nothing could arrest his slow progress. If the lantern were moved I could still distinguish Golo’s horse advancing across the window-curtains, swelling out with their curves and diving into their folds. The body of Golo himself, being of the same supernatural substance as his steed’s, overcame all material obstacles — everything that seemed to bar his way — by taking it as an ossature and embodying it in himself: even the door-handle, for instance, over which, adapting itself at once, would float irresistibly his red cloak or his pale face, never losing its nobility or its melancholy, never betrayed the least concern at this transvertebration.

And, indeed, I found plenty of charm in these bright projections, which seemed to emanate from a Merovingian past and shed around me the reflections of such ancient history. But I cannot express the discomfort I felt at such an intrusion of mystery and beauty into a room which I had succeeded in filling with my own personality until I thought no more of it than of myself. The anaesthetic effect of habit being destroyed, I would begin to think – and to feel – such melancholy things. The door-handle of my room, which was different to me from all the other door-handles in the world, inasmuch as it seemed to open of its own accord and without my having to turn it, so unconscious had its manipulation become – lo and behold, it was now an astral body for Golo. And as soon as the dinner-bell rang I would run down to the dining-room, where the big hanging lamp, ignorant of Golo and Bluebeard but well acquainted with my family and the dish of stewed beef, shed the same light as on every other evening; and I would fall into the arms of my mother, whom the misfortunes of Geneviève de Brabant had made all the dearer to me, just as the crimes of Golo had driven me to a more than ordinarily scrupulous examination of my own conscience.

A Combray, tous les jours dès la fin de l’après-midi, longtemps avant le moment où il faudrait me mettre au lit et rester, sans dormir, loin de ma mère et de ma grand’mère, ma chambre à coucher redevenait le point fixe et douloureux de mes préoccupations. On avait bien inventé, pour me distraire les soirs où on me trouvait l’air trop malheureux, de me donner une lantern e magig ne. dont, en attendant l’heure du dîner, on coiffait ma lampe; et, à l’instar des premiers architectes et maîtres verriers de l’âge gothique,”) elle substituait à l’opacité des murs d’impalpables irisations, de surnaturehes apparitions multicolores, où des légendes étaient dépeintes comme dans un vitrail vacillant et momentané. Mais ma tristesse n’en était qu’accrue, parce que rien que le changement d’éclairage détruisait l’habitude que j’avais de ma chambre et grâce à quoi, sauf le supplice du coucher, elle m’était devenue

supportable. Maintenant je ne la reconnaissais plus et j’y étais inquiet, comme dans une chambre d’hôtel ou de «chalet» où je fusse arrivé pour la première fois en descendant de chemin de fer.

Au pas saccadé de son cheval, Golo, plein d’un affreux dessein, sortait de la petite forêt triangulaire qui veloutait d’un vert sombre la pente d’une colline, et s’avançait en tressautant vers le château de la pauvre Geneviève de Brabant. Ce château était coupé selon une ligne courbe qui n’était guère que la limite d’un des ovales de verre énagés dans le châssis qu’on glissait entre les coulisses de la lanterne. CCe n’était qu’un pan de château, et il avait devant lui une lande où rêvait Geneviève, qui portait une ceinture bleue. Le château et la lande étaient jaunes, et je n’avais pas attendu de les voir pour connaître leur couleur, car, avant les verres du châssis, la sonorité mordorée du nom de Brabant me l’avait montrée avec évidence. Golo s’arrêtait un instant pour écouter avec tristesse le boniment lu à haute voix par ma grand’tante, et qu’il avait l’air de comprendre parfaitement, conformant son attitude, avec une docilité qui n’excluait pas une certaine majesté, aux indications du texte; puis il s’éloignait du même pas saccadé. Et rien ne pouvait arrêter sa lente chevauchée. Si on bougeait la lanterne, je distinguais le cheval de Golo qui continuait à s’avancer sur les rideaux de la fenêtre, se bombant de leurs plis, descendant dans leurs fentes. Le corps de Golo lui-même, d’une essence aussi surnaturelle que celui de sa monture, s’arrangeait de tout obstacle matériel, de tout objet gênant qu’il rencontrait en le prenant comme ossature et en se le rendant intérieur, fût-ce le bouton de la porte sur lequel s’adaptait aussitôt et surnageait invinciblement sa robe rouge ou sa figure pâle toujours aussi noble et aussi mélancolique, mais qui ne laissait paraître aucun trouble de cette transvertébration.

Certes je leur trouvais du charme à ces brillantes projections qui semblaient émaner d’un passé mérovingien et promenaient autour de moi des reflets d’histoire si anciens. Mais je ne peux dire quel malaise me causait pourtant cette intrusion du mystère et de la beauté dans une chambre que j’avais fini par remplir de mon moi au point de ne pas faire plus attention à elle qu’à lui-même. L’influence anesthésiante de l’habitude ayant cessé, je me mettais à penser, à sentir, choses si tristes. Ce bouton de la porte de ma chambre, qui différait pour moi de tous les autres boutons de porte du monde en ceci qu’il semblait ouvrir tout seul, sans que j’eusse besoin de le tourner, tant le maniement m’en était devenu inconscient, le voilà qui servait maintenant de corps astral à Golo. Et dès qu’on sonnait le dîner, j’avais hâte de courir à la salle à manger, où la grosse lampe de la suspension, ignorante de Golo et de Barbe-Bleue, et qui connaissait mes parents et le bœuf à la casserole, donnait sa lumière de tous les soirs, et de tomber dans les bras de maman que les malheurs de Geneviève de Brabant me rendaient plus chère, tandis que les crimes de Golo me faisaient examiner ma propre conscience avec plus de scrupules.

Comments: Marcel Proust (1871-1922) was a French novelist, known for À la recherche du temps perdu which was published in seven parts between 1913 and 1927. The medieval legend of Geneviève de Brabant tells of a wronged nobleman’s wife who is accused of adultery with the treachorous Golo. She escapes execution and hides in a cave for some years, before being discovered by her husband and reinstated. The story has been made the subject of plays, operas and films. The Merovingians were a dynasty of French kings. The close relationship between Proust’s own childhood and that of the narrator in his novel places this incident in the 1870s.

Links: Magic lantern slides depicting the story of Geneviève de Brabant at the Cinémathèque française (illustrated above)