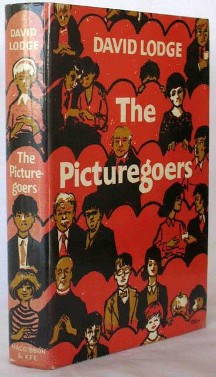

Source: Siegfried Sassoon, ‘Cinema Hero’ in Picture-Show (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1920), pp. 27-28

Text:

O, this is more than fiction! It’s the truth

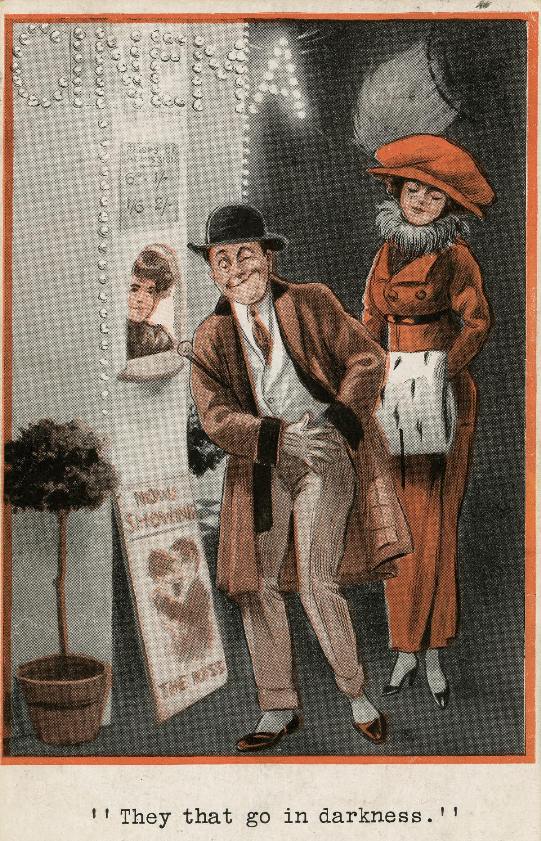

That somehow never happened. Pay your bob,

And walk straight in, abandoning To-day.

(To-day’s a place outside the picture-house;

Forget it, and the film will do the rest.)

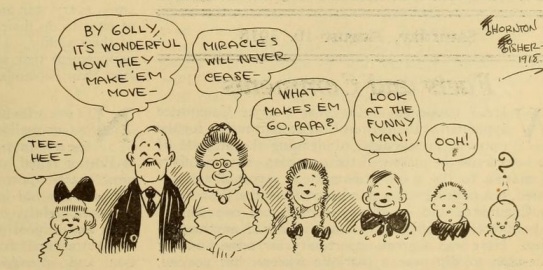

There’s nothing fine in being as large as life:

The splendour starts when things begin to move

And gestures grow enormous. That’s the way

To dramatise your dreams and play the part

As you’d have done if luck had starred your face.

I’m ‘Rupert from the Mountains’! (Pass the stout)…

Yes, I’m the Broncho Boy we watched to-night,

That robbed a ranch and galloped down the creek.

(Moonlight and shattering hoofs. … O moonlight of the West!

Wind in the gum-trees, and my swerving mare

Beating her flickering shadow on the post.)

Ah, I was wild in those fierce days! You saw me

Fix that saloon? They stared into my face

And slowly put their hands up, while I stood

With dancing eyes, — romantic to the world!

Things happened afterwards … You know the story …

The sheriff’s daughter, bandaging my head;

Love at first sight; the escape; and making good

(To music by Mascagni). And at last

Peace; and the gradual beauty of my smile.

But that’s all finished now. One has to take

Life as it comes. I’ve nothing to regret.

For men like me, the only thing that counts

Is the adventure. Lord, what times I’ve had!

God and King Charles! And then my mistress’s arms. …

(To-morrow evening I’m a Cavalier.)

Well, what’s the news to-night about the Strike?

Comments: Siegfried Sassoon (1866-1967) was a British poet, renowned for his poems about the First World War which revealed much of the reality of life in the trenches. This poem comes from his 1919 collection Picture-Show, whose title poem has the famous lines “And still they come and go: and this is all I know / That from the gloom I watch an endless picture-show … And life is just the picture dancing on a screen.”