Source: Stephen Leacock, ‘Madeline of the Movies: A Photoplay Done Back into Words’, in Further Foolishness: Sketches and Satires on the Follies of the Day (New York/London: John Lane, 1917), pp. 133-150

Text: (EXPLANATORY NOTE – In writing this I ought to explain that I am a tottering old man of forty-six. I was born too soon to understand moving pictures. They go too fast. I can’t keep up. In my young days we used a magic lantern. It showed Robinson Crusoe in six scenes. It took all evening to show them. When it was done the hall was filled full with black smoke and the audience quite unstrung with excitement. What I set down here represents my thoughts as I sit in front of a moving picture photoplay and interpret it as best I can.)

Flick, flick, flick … I guess it must be going to begin now, but it’s queer the people don’t stop talking: how can they expect to hear the pictures if they go on talking?

Now it’s off. PASSED BY THE BOARD OF —. Ah, this looks interesting — passed by the board of — wait till I adjust my spectacles and read what it —

It’s gone. Never mind, here’s something else, let me see — CAST OF CHARACTERS — Oh, yes — let’s see who they are —MADELINE MEADOWLARK, a young something — EDWARD DANGERFIELD, a — a what? Ah, yes, a roo — at least, it’s spelt r-o-u-e, that must be roo all right — but wait till I see what that is that’s written across the top — MADELINE MEADOWLARK; OR, ALONE IN A GREAT CITY. I see, that’s the title of it. I wonder which of the characters is alone. I guess not Madeline: she’d hardly be alone in a place like that. I imagine it’s more likely Edward Dangerous the Roo. A roo would probably be alone a great deal, I should think. Let’s see what the other characters are — JOHN HOLDFAST, a something. FARMER MEADOWLARK, MRS. MEADOWLARK, his Something —

Pshaw, I missed the others, but never mind; flick, flick, it’s beginning — What’s this? A bedroom, eh? Looks like a girl’s bedroom — pretty poor sort of place. I wish the picture would keep still a minute — in Robinson Crusoe it all stayed still and one could sit and look at it, the blue sea and the green palm trees and the black footprints in the yellow sand — but this blamed thing keeps rippling and flickering all the time — Ha! there’s the girl herself — come into her bedroom. My! I hope she doesn’t start to undress in it — that would be fearfully uncomfortable with all these people here. No, she’s not undressing — she’s gone and opened the cupboard. What’s that she’s doing — taking out a milk jug and a glass — empty, eh? I guess it must be, because she seemed to hold it upside down. Now she’s picked up a sugar bowl — empty, too, eh? — and a cake tin, and that’s empty — What on earth does she take them all out for if they’re empty? Why can’t she speak? I think — hullo — who’s this coming in? Pretty hard-looking sort of woman—what’s she got in her hand? —some sort of paper, I guess — she looks like a landlady, I shouldn’t wonder if …

Flick, flick! Say! Look there on the screen:

“YOU OWE ME THREE WEEKS’ RENT.”

Oh, I catch on! that’s what the landlady says, eh? Say! That’s a mighty smart way to indicate it isn’t it? I was on to that in a minute — flick, flick — hullo, the landlady’s vanished — what’s the girl doing now — say, she’s praying! Look at her face! Doesn’t she look religious, eh?

Flick, flick!

Oh, look, they’ve put her face, all by itself, on the screen. My! what a big face she’s got when you see it like that.

She’s in her room again — she’s taking off her jacket—by Gee! She is going to bed! Here, stop the machine; it doesn’t seem — Flick, flick!

Well, look at that! She’s in bed, all in one flick, and fast asleep! Something must have broken in the machine and missed out a chunk. There! she’s asleep all right—looks as if she was dreaming. Now it’s sort of fading. I wonder how they make it do that? I guess they turn the wick of the lamp down low: that was the way in Robinson Crusoe — Flick, flick!

Hullo! where on earth is this — farmhouse, I guess — must be away upstate somewhere — who on earth are these people? Old man — white whiskers — old lady at a spinning-wheel — see it go, eh? Just like real! And a young man — that must be John Holdfast — and a girl with her hand in his. Why! Say! it’s the girl, the same girl, Madeline — only what’s she doing away off here at this farm — how did she get clean back from the bedroom to this farm? Flick, flick! what’s this?

“NO, JOHN, I CANNOT MARRY YOU. I MUST DEVOTE MY LIFE TO MY MUSIC.”

Who says that? What music? Here, stop —

It’s all gone. What’s this new place? Flick, flick, looks like a street. Say! see the street car coming along — well! say! isn’t that great? A street car! And here’s Madeline! How on earth did she get back from the old farm all in a second? Got her street things on — that must be music under her arm — I wonder where — hullo — who’s this man in a silk hat and swell coat? Gee! he’s well dressed. See him roll his eyes at Madeline! He’s lifting his hat — I guess he must be Edward Something, the Roo — only a roo would dress as well as he does — he’s going to speak to her —

“SIR, I DO NOT KNOW YOU. LET ME PASS.”

Oh, I see! The Roo mistook her; he thought she was somebody that he knew! And she wasn’t! I catch on! It gets easy to understand these pictures once you’re on.

Flick, flick — Oh, say, stop! I missed a piece — where is she? Outside a street door — she’s pausing a moment outside — that was lucky her pausing like that — it just gave me time to read EMPLOYMENT BUREAU on the door. Gee! I read it quick.

Flick, flick! Where is it now? — oh, I see, she’s gone in — she’s in there — this must be the Bureau, eh? There’s Madeline going up to the desk.

“NO, WE HAVE TOLD YOU BEFORE, WE HAVE NOTHING …”

Pshaw! I read too slow — she’s on the street again. Flick, flick!

No, she isn’t — she’s back in her room — cupboard still empty — no milk — no sugar — Flick, flick!

Kneeling down to pray — my! but she’s religious — flick, flick — now she’s on the street — got a letter in her hand—what’s the address — Flick, flick!

Mr. Meadowlark

Meadow Farm

Meadow County

New York

Gee! They’ve put it right on the screen! The whole letter!

Flick, flick — here’s Madeline again on the street with the letter still in her hand — she’s gone to a letter-box with it — why doesn’t she post it? What’s stopping her?

“I CANNOT TELL THEM OF MY FAILURE. IT WOULD BREAK THEIR …”

Break their what? They slide these things along altogether too quick — anyway, she won’t post it — I see —s he’s torn it up — Flick, flick!

Where is it now? Another street — seems like everything — that’s a restaurant, I guess — say, it looks a swell place — see the people getting out of the motor and going in — and another lot right after them — there’s Madeline — she’s stopped outside the window — she’s looking in — it’s starting to snow! Hullo! here’s a man coming along! Why, it’s the Roo; he’s stopping to talk to her, and pointing in at the restaurant — Flick, flick!

“LET ME TAKE YOU IN HERE TO DINNER.”

Oh, I see! The Roo says that! My! I’m getting on to the scheme of these things — the Roo is going to buy her some dinner! That’s decent of him. He must have heard about her being hungry up in her room — say, I’m glad he came along. Look, there’s a waiter come out to the door to show them in — what! she won’t go! Say! I don’t understand! Didn’t it say he offered to take her in? Flick, flick!

“I WOULD RATHER DIE THAN EAT IT.”

Gee! Why’s that? What are all the audience applauding for? I must have missed something! Flick, flick!

Oh, blazes! I’m getting lost! Where is she now? Back in her room — flick, flick — praying — flick, flick! She’s out on the street! — flick, flick! — in the employment bureau — flick, flick! — out of it — flick — darn the thing! It changes too much — where is it all? What is it all —? Flick, flick!

Now it’s back at the old farm — I understand that all right, anyway! Same kitchen — same old man — same old woman — she’s crying — who’s this? — man in a sort of uniform — oh, I see, rural postal delivery — oh, yes, he brings them their letters — I see —

“NO, MR. MEADOWLARK, I AM SORRY, I HAVE STILL NO LETTER FOR YOU …”

Flick! It’s gone! Flick, flick — it’s Madeline’s room again — what’s she doing? — writing a letter? — no, she’s quit writing — she’s tearing it up —

“I CANNOT WRITE. IT WOULD BREAK THEIR …”

Flick — missed it again! Break their something or other — Flick, flick!

Now it’s the farm again — oh, yes, that’s the young man John Holdfast — he’s got a valise in his hand — he must be going away — they’re shaking hands with him — he’s saying something —

“I WILL FIND HER FOR YOU IF I HAVE TO SEARCH ALL NEW YORK.”

He’s off — there he goes through the gate — they’re waving good-bye — flick — it’s a railway depot — flick — it’s New York — say! That’s the Grand Central Depot! See the people buying tickets! My! isn’t it lifelike? — and there’s John — he’s got here all right — I hope he finds her room —

The picture changed — where is it now? Oh, yes, I see — Madeline and the Roo — outside a street entrance to some place — he’s trying to get her to come in — what’s that on the door? Oh, yes, DANCE HALL — Flick, flick!

Well, say, that must be the inside of the dance hall — they’re dancing — see, look, look, there’s one of the girls going to get up and dance on the table.

Flick! Darn it! — they’ve cut it off — it’s outside again — it’s Madeline and the Roo — she’s saying something to him —my! doesn’t she look proud —?

“I WILL DIE RATHER THAN DANCE.”

Isn’t she splendid! Hear the audience applaud! Flick — it’s changed — it’s Madeline’s room again — that’s the landlady — doesn’t she look hard, eh? What’s this — Flick!

“IF YOU CANNOT PAY, YOU MUST LEAVE TO-NIGHT.”

Flick, flick — it’s Madeline — she’s out in the street — it’s snowing — she’s sat down on a doorstep — say, see her face, isn’t it pathetic? There! They’ve put her face all by itself on the screen. See her eyes move! Flick, flick!

Who’s this? Where is it? Oh, yes, I get it — it’s John — at a police station — he’s questioning them — how grave they look, eh? Flick, flick!

“HAVE YOU SEEN A GIRL IN NEW YORK?”

I guess that’s what he asks them, eh? Flick, flick —

“NO, WE HAVE NOT.”

Too bad — flick — it’s changed again — it’s Madeline on the doorstep — she’s fallen asleep — oh, say, look at that man coming near to her on tiptoes, and peeking at her — why, it’s Edward, it’s the Roo — but he doesn’t waken her — what does it mean? What’s he after? Flick, flick —

Hullo — what’s this? — it’s night — what’s this huge dark thing all steel, with great ropes against the sky — it’s Brooklyn Bridge — at midnight — there’s a woman on it! It’s Madeline — see! see! She’s going to jump — stop her! Stop her! Flick, flick —

Hullo! she didn’t jump after all — there she is again on the doorstep — asleep — how could she jump over Brooklyn Bridge and still be asleep? I don’t catch on —or, oh, yes, I do — she dreamed it — I see now, that’s a great scheme, eh? — shows her dream —

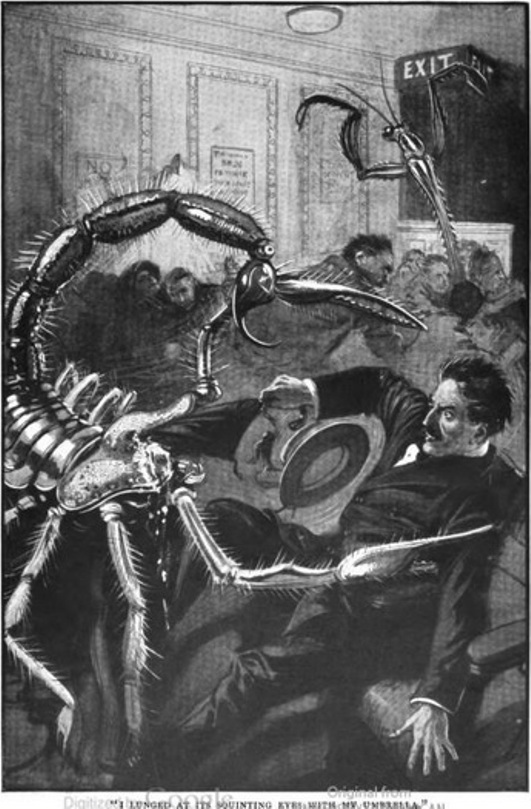

The picture’s changed — what’s this place — a saloon, I guess — yes, there’s the bartender, mixing drinks — men talking at little tables — aren’t they a tough-looking lot? — see, that one’s got a revolver — why, it’s Edward the Roo — talking with two men — he’s giving them money — what’s this? —

“GIVE US A HUNDRED APIECE AND WE’LL DO IT.”

It’s in the street again — Edward and one of the two toughs —they’ve got little black masks on — they’re sneaking up to Madeline where she sleeps — they’ve got a big motor drawn up beside them — look, they’ve grabbed hold of Madeline — they’re lifting her into the motor — help! Stop! Aren’t there any police? — yes, yes, there’s a man who sees it — by Gee! It’s John, John Holdfast — grab them, John — pshaw! they’ve jumped into the motor, they’re off!

Where is it now? — oh, yes — it’s the police station again — that’s John, he’s telling them about it — he’s all out of breath — look, that head man, the big fellow, he’s giving orders —

“INSPECTOR FORDYCE, TAKE YOUR BIGGEST CAR AND TEN MEN. IF YOU OVERTAKE THEM, SHOOT AND SHOOT TO KILL.”

Hoorah! Isn’t it great — hurry! don’t lose a minute — see them all buckling on revolvers — get at it, boys, get at it! Don’t lose a second —

Look, look — it’s a motor — full speed down the street —look at the houses fly past — it’s the motor with the thugs — there it goes round the corner — it’s getting smaller, it’s getting smaller, but look, here comes another my! it’s just flying — it’s full of police — there’s John in front — Flick!

Now it’s the first motor — it’s going over a bridge — it’s heading for the country —s ay, isn’t that car just flying —Flick, flick!

It’s the second motor — it’s crossing the bridge too — hurry, boys, make it go! — Flick, flick!

Out in the country — a country road — early daylight — see the wind in the trees! Notice the branches waving? Isn’t it natural? — whiz! Biff! There goes the motor — biff! There goes the other one — right after it — hoorah!

The open road again — the first motor flying along! Hullo, what’s wrong? It’s slackened, it stops — hoorah! it’s broken down — there’s Madeline inside — there’s Edward the Roo! Say! isn’t he pale and desperate!

Hoorah! the police! the police! all ten of them in their big car —see them jumping out — see them pile into the thugs! Down with them! paste their heads off! Shoot them! Kill them! isn’t it great — isn’t it educative —that’s the Roo — Edward — with John at his throat! Choke him, John! Throttle him! Hullo, it’s changed — they’re in the big motor — that’s the Roo with the handcuffs on him.

That’s Madeline — she’s unbound and she’s talking; say, isn’t she just real pretty when she smiles?

“YES, JOHN, I HAVE LEARNED THAT I WAS WRONG TO PUT MY ART BEFORE YOUR LOVE. I WILL MARRY YOU AS SOON AS YOU LIKE.”

Flick, flick!

What pretty music! Ding! Dong! Ding! Dong! Isn’t it soft and sweet! — like wedding bells. Oh, I see, the man in the orchestra’s doing it with a little triangle and a stick — it’s a little church up in the country — see all the people lined up — oh! there’s Madeline! in a long white veil — isn’t she just sweet! — and John —

Flick, flack, flick, flack.

“BULGARIAN TROOPS ON THE MARCH.”

What! Isn’t it over? Do they all go to Bulgaria? I don’t seem to understand. Anyway, I guess it’s all right to go now. Other people are going.

Comments: Stephen Leacock (1869-1944) was a Canadian humorist who was probably the most popular comic writer of his day. In the printed text the mock intertitles are presented in boxes.

Links: Copy on Internet Archive