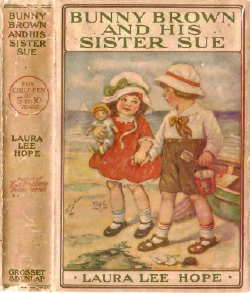

Source: Laura Lee Hope, extract from Bunny Brown and his Sister Sue (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1916)

Text: Just beyond the corner there was a moving picture theatre, lately opened. Mrs. Brown and Aunt Lu had taken Bunny and his sister there once or twice, when there was a fairy play, or something nice to see, so Bunny and Sue knew what the moving pictures were like.

Text: Just beyond the corner there was a moving picture theatre, lately opened. Mrs. Brown and Aunt Lu had taken Bunny and his sister there once or twice, when there was a fairy play, or something nice to see, so Bunny and Sue knew what the moving pictures were like.

“Oh, let’s just go down and look at the picture posters outside,” said Bunny, as they stood on the corner, from where they could see the theatre.

“All right,” said Sue quickly.

In front of the moving picture place were some big boards, and on them were pasted brightly colored posters, almost like circus ones, telling about the moving pictures that were being shown inside. There was a picture of a man falling in the water, and another of a railroad train. Bunny loved cars and locomotives.

Not thinking anything wrong, the two tots ran across the street, looking carefully up and down first, to see that no automobiles were coming. They crossed safely.

A little later they were standing in front of the moving picture theatre, looking at the gay posters.

“Wouldn’t you like to go in?” asked Bunny.

Sue nodded her curly head.

“Maybe Aunt Lu will take us,” she said.

“We’ll ask her,” decided Bunny.

Then they heard, from down the side street, the sound of a piano. It came from the moving picture place, and the reason Bunny and Sue could hear it so plainly was because the piano was near a side door, which was open to let in the fresh air.

“Let’s go down there and listen to the music a minute,” Bunny said. “Then we’ll go back and tell Aunt Lu.”

“All right!” agreed Sue.

A little later the two were standing at the open, side door of the place. They could hear the piano very plainly now, and, what was more wonderful, they could look right in the theatre and see the moving pictures flashing on the white screen.

“Oh! oh!” murmured Bunny. “Look, Sue.”

“Oh! oh!” whispered Sue. And then Bunny had a queer idea.

“We can walk right in,” he said. “The door is open. I guess this is for children like us – they don’t want any money. Come on in, Sue, and we’ll see the moving pictures!”

Bunny Brown and his sister Sue walked right into the moving picture theatre. The door, as I have told you, was open, there was no one standing near to take tickets, or ask for money, and of course the children thought it was all right to go in.

No one seemed to notice them, perhaps because the place was dark, except where the brilliant pictures were dancing and flashing on the white screen. And no one heard Bunny and Sue, for not only did they walk very softly, but just then the girl at the piano was playing loudly, and the sound filled the place.

Right in through the open side door walked Bunny and Sue, and never for a moment did they think they were doing anything wrong. I suppose, after all, it was not very wrong.

Bunny walked ahead, and Sue followed, keeping hold of his hand. Pretty soon she whispered to her brother:

“Bunny! Bunny! I can’t see very good at all here. I want to see the pictures better.”

“All right,” Bunny whispered back. “I can’t see very good, either. We’ll find a better place.”

You know you can’t look at moving pictures from the side, they all seem to be twisted if you do. You must be almost in front of them, and this time Bunny and Sue were very much to one edge.

“We’ll get up real close, and right in front,” Bunny went on. Then he saw a little pair of steps leading up to the stage, or platform; only Bunny did not know it was that. He just thought if he and Sue went up the steps they would be better able to see. So up he went.

The screen, or big white sheet, on which the moving pictures were shown, stood back some distance from the front of the stage. And it was a real stage, with footlights and all, but it was not used for acting any more, as only moving pictures were given in that theatre now.

Sue followed Bunny up the steps. The pictures were ever so much clearer and larger now. She was quite delighted, and so was her brother. They wandered out to the middle of the stage, paying no attention to the audience. And the people in the theatre were so interested in the picture on the screen, that, for a while, they did not see the children who had wandered into the darkened theatre by the side door.

The music from the piano sounded louder and louder. The pictures became more brilliant. Then suddenly Bunny and Sue walked right out on the stage in front of the screen, where the light from the moving picture lantern shone brightly on them.

“What’s that?” cried several persons.

“Look! Why they’re real children!” said others.

Bunny and Sue could be plainly seen now, for they were exactly in the path of the strong light. There was some laughter in the audience, and then the man who was turning the crank of the moving picture machine began to understand that something was wrong.

He stopped the picture film, and turned on a plain, white light, very strong and glaring, Just like the headlights of an automobile. Bunny and Sue could hardly see, and they looked like two black shadows on the white screen.

“Look! Look! It’s part of the show!” said some persons in front.

“Maybe they’re going to sing,” said others.

“Or do a little act.”

“Oh, aren’t they cute!” laughed a lady.

By this time the piano player had stopped making music. She knew that something was wrong. So did the moving picture man up in his little iron box, and so did the usher – that’s the man who shows you where to find a seat. The usher came hurrying down the aisle.

“Hello, youngsters!” he called out, but he was not in the least bit cross. “Where did you get in?” he asked.

By this time the lights all over the place had been turned up, and Bunny and Sue could see the crowd, while the audience could also see them. Bunny blinked and smiled, but Sue was bashful, and tried to hide behind her brother. This made the people laugh still more.

“How did you get in, and who is with you?” asked the usher.

“We walked in the door over there,” and Bunny pointed to the side one. “And we came all alone. We’re waiting for Aunt Lu.”

“Oh, then she is coming?”

“I don’t guess so,” Bunny said. “We didn’t tell her we were coming here.”

“Well, well!” exclaimed the usher-man. “What does it all mean? Did your Aunt Lu send you on ahead? We don’t let little children in here unless some older person is with them, but -”

“We just comed in,” Sue said. “The door was open, and we wanted to see the pictures, so we comed in; didn’t we Bunny?”

“Yes,” he said. “But we’d like to sit down. We can’t see good up here.”

“No, you are a little too close to the screen,” said the usher. “Well, I’d send you home if I knew where you lived, but–”

“I know them!” called out a woman near the front of the theatre. “That is Bunny Brown and his sister Sue. They live just up the street. I’ll take them home.”

“Thank you; that’s very kind of you,” said the man. “I guess their folks must be worrying about them. Please take them home.”

“We don’t want to go home!” exclaimed Sue. “We want to see the pictures; don’t we, Bunny?”

“Yes,” answered the little fellow, “but maybe we’d better go and get Aunt Lu.”

“I think so myself,” laughed the usher. “You can come some other time, youngsters. But bring your aunt, or your mother, with you; and don’t come in the side door. I’ll have to keep some one there, if it’s going to be open, or I’ll have more tots walking in without paying.”

“Come the next time, with your aunt or mother,” he went on, “and I’ll give you free tickets. It won’t cost you even a penny!”

“Oh, goodie!” cried Sue. She was willing to go home now, and the lady who said she knew them – who was a Mrs. Wakefield, and lived not far from the Brown home – took Bunny and Sue by the hands and led them out of the theatre.

The lights were turned low again, and the moving picture show went on. Bunny and Sue wished they could have stayed, but they were glad they could come again, as the man had invited them.

Comments: Laura Lee Hope was a pseudonym used by American book publisher the Stratemeyer Syndicate to produce books for children, including Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, and Bunny Brown and his Sister Sue. The latter series, aimed at young children, was published 1916-1930.

Links: Copy on Project Gutenberg