Source: Anon., ‘Kinoplastikon: As Seen From the Stalls’, The Bioscope, 8 May 1913, p. 391

Text: The cinematograph industry, from its very inception, has been so prolific of novelties and sensations, that we have now grown almost accustomed to living in a condition of perpetual astonishment. The biggest surprise of all, of course, was the cinematograph itself, but since then we have had colour films. speaking films, singing films – in fact, films of almost every character it is possible to imagine or desire. Celluloid has become the embryo of a new universe, which seems to contain everything that was in the old world, and a great deal besides that the old world never dreamed of.

One of the latest wonders to come forth from the inexhaustible womb of the moving picture camera is kinoplastikon, the remarkable “living, singing, talking camera pictures,” of which, as our readers will remember, an enthusiastic description was given in our issue of March 20th. by our special correspondent, Mr. John Cher, who saw them in Vienna, before they had been brought to this country. As most people know, they have now come to England, and are to be seen each night in the west-end of London, at the beautiful Scala Theatre, where we had the pleasure of making their acquaintance the other evening.

Kinoplastikon pictures are certainly very surprising when you first set eyes on them, especially when they come, as they do at the Scala, in the middle of a programme of ordinary cinematograph films. The curtain goes up, and the stage is revealed, bare, to all appearance, of everything but a conventional set. Then, suddenly, you hear the grating of a gramophone beginning to work. The orchestra strikes up in accompaniment. And, without warning, two white pierrots dance on from the wings – as naturally and as easily as though they were beings of real flesh and blood. They give a xylophone duet – their instrument apparently resting on a table which has been placed there beforehand, in full view of the audience, by a solid human attendant – and then, their performance finished, they skip off the stage to make their bows in answer to the riotous storm of applause which marks the conclusion of their “turn.” Five other pictures follow, one of them a flute solo and the other vocal performances.

The appearance of these amazing spirit creatures is curious. They resemble the figures of an ordinary cinematograph film, cut away from their original background with a pair of scissors, and set to caper and gesticulate, their vitality unimpaired, upon a wooden stage. Some of them are in black and white only; others are coloured artificially.

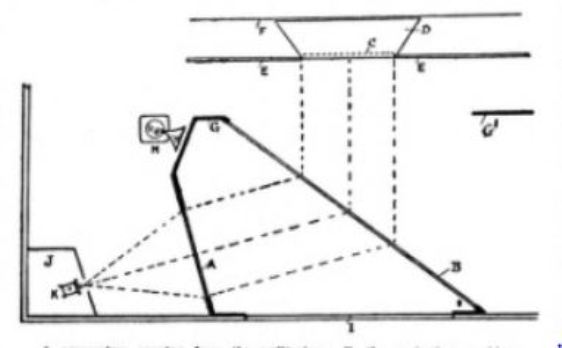

To offer any explanation of how Kinoplastikonis “worked” would be imprudent without investigating it more closely – and we have not yet had an opportunity of examining these “picture people,” except at a respectful distance from the auditorium. Speaking without prejudice, one would imagine that they are related, more or less nearly, to the famous ghosts of the late lamented Professor Pepper, the maker of mirror miracles. They are advertised as being presented “without a screen”; one rather fancies, however, that the screen is invisible, as, on the left-hand side of the stage, the creatures disappeared a trifle before they reached the wings. In, mid-air, also, are occasionally noticed white spots, which seemed to suggest scratches upon a black film.

Kinoplastikon produces a stereoscopic effect, because the figures in its films stand in the middle of an ordinary stage, and thus really have space before and behind them, In themselves, however, they are not stereoscopic, a fact which was observable in the last film shown, where a woman stood in front of several other people, the latter appearing unnaturally small and out of perspective, as is the case in an ordinary photograph.

It is difficult to make speculations about the future of Kinoplastikon without knowing more of its modus operandi. Even if it accomplishes nothing more than the sort of thing which may be seen at the Scala, however, it may always be safely relied upon to make a novel and effective item in a variety programme. And it certainly constitutes a remarkably fine example of the “talking picture.”

Comments: Kinoplastikon was a means of showing coloured motion pictures, with sound, in stereoscopic relief. The original system was the invention of the German film pioneer Oskar Messter, who named it ‘Alabastra’. Based on the ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ stage illusion, whereby seemingly life-like images could appear on stage via reflected projection from a mirror, Messter extended the idea to employ motion picture film, hand tinted and with musical accompaniment. An adaptation of Alabastra was exhibited in Vienna under the name Kinoplastikon, subsequently appearing in Britain in 1913 at the Scala Theatre, London. The films were produced in a studio lined with black velvet (the actors had to be dressed entirely in white) on the roof of the Scala theatre, with synchonrised sound-on-disc accompaniment using Cecil Hepworth’s Vivaphone system. The director was Walter Booth. As the reviewer suspected, a screen was used, though hidden from view.

Kinoplastikon excited much comment, with suggestions that it was the future of entertainment, but as Hepworth observes in his autobiography, Came the Dawn, “It suffered, I suspect, from the usual fate which almost always dogs the steps of any ghost-illusion. Very few people are interested in an illusion of that kind as an illusion. They may think it is clever but do not bother to wonder how it is done; they don’t even care. Unless it tells some story, or belongs to some story which cannot well be told without it. it very soon ceases to intrigue them”. Kinoplastikon was exhibited in Austria, Britain, France, Russia and the USA, but it swiftly disappeared.