Source: John Durrant, extract from ‘The Movies Take to the Pastures’, Saturday Evening Post, 14 October 1950. pp. 25, 85, 89

Text: For the fifth year in a row now movie attendance has been going down, down, down like Alice’s plunge to the bottom of the rabbit hole in her Wonderland adventure. The cinema dive, though, is no dream. It is real, and the industry is chewing its nails, wondering whether to blame its favorite whipping boy, television; the 20 per cent Federal tax on tickets; strikes and war fears; Hollywood’s pinkish tint, or too-good weather, which is supposed to keep the customers away from the movies. Whatever the causes, attendance has been slipping away steadily, although recent figures indicate that the decline may now be slowing up. Tbere is, however, one phase of the industry which has been running contrary to the general trend and bringing smiles to an increasing number of exhibitors.

It is the drive-in business, which has expanded phenomenally since the end of World War I. At the time of Pearl Harbor, for instance, there were less than 100 “ozoners” in the country. None was built during the war, but by 1947 there were 400, double that number the following year and now there are a probable 2200 in the United States and forty in Canada.

As one movie mogul famous for his malapropisms said, “They are sweeping the country like wildflowers.” And Bob Hope recently commented, “There will soon be so many drive-ins in California that you’ll be able to get married, have a honeymoon and get a divorce without ever getting out of your car.”

Hope is not exaggerating too wildly. Here, for instance, are some of the things you can do at various ozoners without taking your eyes off the screen or missing a word of dialogue: You can eat a complete meal, get your car washed and serviced, including a change of tires, have the week’s laundry done, your shopping list filled and the baby’s bottle warmed. All this while the show is on.

It’s a cinch to attend a drive-in. You buy a ticket without getting out of your car, drive to one of the rows and take a position on a ramp which causes the car to tilt slightly upward at the front end. Alongside there’s a speaker, attached to a post, which you unhook and fasten to the inside of your car window. Volume can be controlled by turning a switch, and although at first it may seem odd to be hearing sounds from a speaker next to your ear, with the action on the screen a couple of hundred yards away, the illusion is acceptable. If you want to leave in the middle of the show you replace the speaker in the post and drive forward over the ramp and make for the exit. Thus, there is no climbing over the laps of annoyed spectators as there is in the conventional theaters.

If Hope thinks that California is becoming overcrowded with drive-ins, be should visit Ohio and North Carolina, where every cow pasture is crowned by a screen. North Carolina, about one third the size of California in both population and area, boasts 125 ozoners to California’s ninety-five. Ohio has 135. While Califomia’s theaters are larger and hold more cars, the concentration of so many ozoners in the two other states is way out of proportion to their size. Why, no one knows. But the business is full of oddities. Texas, as you might expect, leads the country with some 200 theaters. Then come Ohio, North Carolina and Pennsylvania in that order, followed by California, where the drive-ins operate the year round and everybody owns a car.

Due to the rapidity of construction – and closings, in some regions – the business is in a constant state of flux, and figures are changing daily. One thing is apparent, however, and that is that the trend is up and the saturation point has not yet been reached. When it comes – movie people put it at 3500 drive-ins – it is anybody’s guess whether there will be like the miniature-golf-course fiasco in the 30s, or a gradual leveling off, with the best-run theaters surviving.

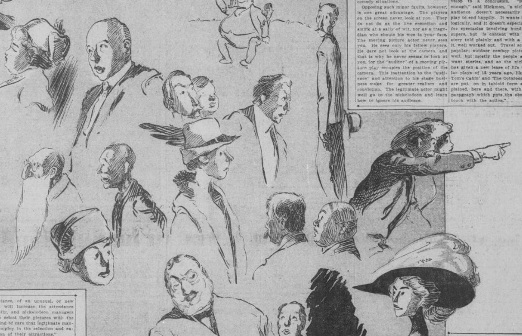

Most conventional theater owners, who despise the ozoners and battle them at every turn, say the thing is a fad, that it’s going too fast and, anyway, the places are no more than parking lots for petters. Variety, the bible of show business calls them “passion pits with pix.” Needless to there are no figures on petting frequency in drive-ins, but I can offer the result of a one-man nonsnooping survey made by myself. I talked with dozens of exhibitors, and all firmly stated that no more went on in the cars than in the rear seats of the conventional theaters. All were quite touchy on the subject, by the way. Only one said he had ever had a complaint in that direction from a patron.

Leon Rosen, who has managed both types of theaters for the Fabian Theaters, a chain of eighty conventionals and seven drive-ins in the Middle Atlantic states, told me that more than 3,000,000 people have attended the ozoners he’s managed and he has never received a single complaint. He could not say the same for his indoor theaters. “Sure, a fellow slips his arm around his girl in the drive-ins,” he said. “The same as in the regular theaters or on a park bench. No more than that. And there’s one thing you don’t get in the drive-ins that you get inside. That’s the guy on the prowl, the seat changer who molests lone women. There’s none of that in the drive-ins.”

Still, the bad name persists and is kept alive by gents’-room gags which probably stem from the prewar days, when drive-ins were completely blacked out and circulating food venders and ushers were a rarity. But what disproves the cheap gags more than anything else is the type of audience that fills the drive-ins today. It is by far a family audience, with a probable 75 per cent of the cars containing children who, incidentally, are let in free by most drive-ins if they are under twelve. This is the main reason the ozoners have been so successful – their appeal to the

family group. They are the answer to parents who want to take in the movies, but can’t leave their children alone at home. No baby sitters are needed. And the kids are no bother to anyone in the audience. There’s no vaulting of theater seats, running up and down the aisles or drowning out the dialogue by yapping.

A workingman told me that the drive-ins had saved his family from a near split-up. He didn’t like the movies, he said, and his wife did. The result was a battle every Saturday night, when she wanted to see a movie and he refused to go. Saturday night was his beer night, and no movies were going to interfere with it. His wife went anyway, and he stayed home sipping beer and keeping an eye on Junior. But this didn’t work out. The weekly argument went on, and the breach between them got wider. Then, one Saturday night, he agreed to take in a drive-in with her, provided he could take a long a couple of bottles of beer. After that everything was solved. They now go every Saturday night. She sits in the front seat with Junior and watches the flickers. He sits in back alone, with his beer in a bucket of ice, and pays little attention to the movie as he sips the brew and smokes cigars with his legs crossed. Now everybody is happy and there’s no more talk of a split-up.

After the war, the drive-ins began to go all out for the family trade. The so-called “moonlight” flooding of the parking area and aisle lighting came in, and exhibitors built children’s play areas, with swings, slides, merry-go-rounds and pony rides. Some installed miniature railroads which hauled kids over several hundred yards of track. Picnic grounds, swimming pools and monkey villages appeared in the larger theaters. While the youngsters disport themselves at these elaborate plants, their parents can have a go at miniature golf courses and driving ranges or they can play shuffleboard, pitch horse-shoes and dance before live bands.

That is the trend now in the de luxe drive-ins, ones with a capacity of, say, 800 cars or more. They are becoming community recreation centers, and the idea is to attract people two or three hours before show time. It gives the receipts a boost and the family a whole evening’s outing, not just three hour sat the movies, according to the new school of exhibitors. Many old-time managers disagree.

“This carnival stuff cheapens the business,” one told me. “And the biggest mistake the drive-ins made was to let kids in free. They can’t go to the indoor houses for nothing, so a lot of people think we show only rotten pictures and they stay away.”

The manager touched a sore point here. The films shown in the ozoners are in the main pretty frightful. Most are third-run pictures, rusty with age. Drive-in exhibitors are not entirely to blame for this. Film distributors point out that their first loyalty is to their regular customers, the all-year conventional houses, and the ozoners must wait in line or pay through the nose.

It doesn’t seem to make much difference what kind of pictures are shown, because drive-in fans are far less choosy than the indoor variety. A large part of them never have been regular indoor movie-goers, and almost any picture is new to them. The ozoners have struck a rich vein of new fans. Leading the list are the moderate-income families who bring the kids to save money on baby-sitters. Furthermore, they don’t have to dress up, find a parking place, walk a few blocks to a ticket booth and then stand in line. The drive-ins make it easy for them and for workers and farmers, who can come in their working clothes straight from the evening’s chores, and for the aged and physically handicapped. They are a boon to the hard of hearing and to invalids, many of whom never saw a movie before the drive-ins. They draw fat men who have trouble wedging themselves between the arms of theater seats, and tall men sensitive about blocking off the screen from those behind. Add the teen-agers to these people, and you have a weekly attendance of about 7,000,000, an impressive share of the country’s 60,000,000 weekly ticket buyers …

Comments: Drive-ins were introduced in the United States in 1933.

Links: Complete article on Saturday Evening Post site