Source: Robert J. Casey, The Land of Haunted Castles (New York: The Century Co., 1921), pp. 239-255

Text: They don’t go to the opera.

Luxemburg has no opera.

They go to the cinema!

Luxemburg is by history and environment a cinema in itself,—in the midst of natural grandeur is the omnipresent conspiracy of the story-books.

The larger powers play for a great stake and the existence of this tiny duchy is tolerated for purely strategic reasons. A war is waged and a great army sweeps over it—confident of victory—and back, inglorious in defeat. A charming duchess plays politics and loses. Strangers sit in conference in a strange land and calmly determine the fate of her abandoned throne. The while petty conspirators plan revolutions, installing new governments, reinstating old, vacillating betwixt republic and monarchy, immensely proud of themselves and all unmindful of the exterior forces that work their ruin.

Had the novelists designed this country to suit themselves they could have done no better.

A gendarme—or was it a general?—surveyed all comers with a critical eye from a point of vantage in the shelter of a high battlemented building. There was snow in his cerise plume and frost upon the shoulders of his green overcoat that robbed his silver epaulets of their effect. But in his serene dignity he stood as Ajax might have stood in his celebrated dispute with the lightning.

He was impressive enough to have spoiled the business of many a European moving-picture house and brilliant enough to have attracted great quantities of dimes to the cinema palaces of the United States.

One had only to see the disdainful glance which he bestowed upon the Luxembourgeoise questing the joys of the film to see that he disapproved of such idle pursuits. The grown-ups passed him with haughty antagonism. The children hurried by with sidelong glances as if fearful that this splendid figure might interpose himself between them and the doorway behind which flickered the delectable movies.

Once one had braved the guardian at the gate, the way led up three little stone steps to a door common enough in American cottages of twenty years ago,—three panels of wood, a pane of glass, and a wealth of iron grating.

It didn’t look much like the entrance to a theater, but, for that matter, nothing in Graystork looks like what it’s supposed to be. The house was a narrow, three-story stone affair with slim windows and green shutters. A sign over the door proclaimed it to be a cafe. A second sign, obviously a generation or two younger, conveyed the added information that the cinema might be found here and that English was spoken.

I pushed down on the brass lever—there are no door-knobs in Luxemburg—and stepped in out of the blizzard.

There was an instant impression of bar glass, electric lights, tables, straight-backed chairs, and warmth, with an all-pervading atmosphere of hot rum. Some civilians in velour hats and tight-fitting overcoats looked up from their steaming drinks as we added ourselves to the party.

The Kellner, whose memory of Americans hadn’t been entirely obliterated by the long hiatus in the tourist business, came running over from the cage-like bar to bid us welcome.

But we hadn’t come to study the liquid nourishment of Ettelbruck. A book may be written on that particular subject some day, if some brave soul manages to live through the dangers of personal research. Meerschaart instantly removed Herr Kellner’s doubts concerning the cause of our visit with a question:

“Ou est la cinema?”

Herr Kellner looked shocked, then turned to me.

“You will find the moving pictures,” he said in a good brand of Minnesota English, “at the end of the hallway through that little door.” He indicated a door behind the bar, and added graciously as we started to follow his directions:

“For ten years I lived in the United States.”

We walked behind the bar, and a narrow squeeze it was between the porcelain counter and the shelf of glass-ware. With the venturesome air that befitted the circumstances, I opened the door and crossed the threshold into a cold corridor.

Here was a foyer unique in the world of theatricals. Meerschaart may have been prepared for it—for, after all, his country and this are half-sisters—but nothing in my experience had given me warning. Women’s clothes, some very intimate articles of wearing-apparel, hung upon a row of hooks along one side of the hall. I hesitated a moment.

“We’re breaking into somebody’s bedroom,” I declared.

“Maybe that’s where they have the cinema,” returned the Belgian, in a matter-of-fact tone. “Either there or in the kitchen.”

The atmosphere of the corridor, redolent of garlic and boiled cabbage, seemed to give assurance that supper was to be served somewhere soon, but as yet we had no right to leap at conclusions. Anything might happen before we came to the exit.

Beyond the clothes-hooks was another door. We passed through it into a big bare room with plain white walls hung with ancient champagne advertisements. On the side opposite the entrance was a double doorway curtained with red chenille hangings, and at one side of it was a table where a woman, probably the owner of the clothes in the hallway, sold tickets.

The entrance fee was three francs apiece. The original cost, however, was the only expense that had to be figured in the afternoon’s entertainment. No tip was expected by the “usherette” inasmuch as there was no “usherette,” and there was no charge for the program, that being salvaged from the floor in the vicinity of one’s seat.

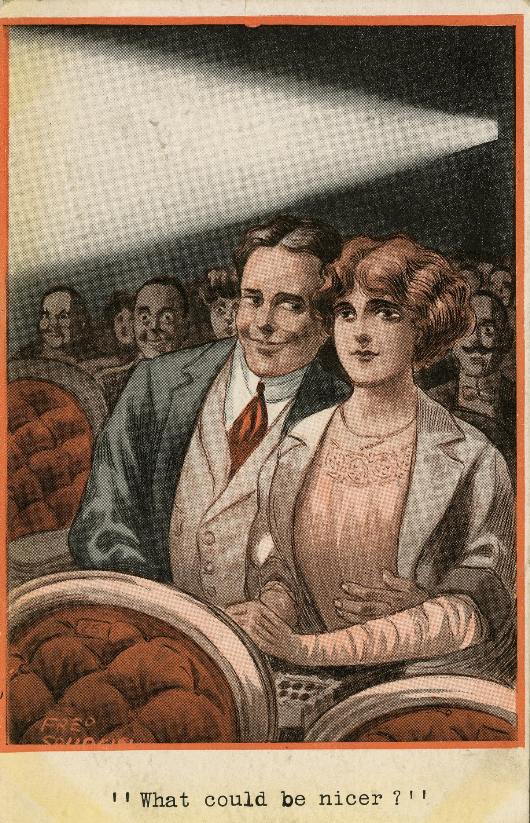

A reel of post-war comedy showing the triumph of President Wilson over a caricature of the kaiser—an animated cartoon of the French school—was just flickering to a close as we entered. The spectators, whom we could not see in the gloom, were dutifully applauding. How much of this frantic enthusiasm was due to inward faith and how much to public policy it would be difficult to say.

National ideas in a country like Luxemburg are bound to change as conditions which affect the national existence are altered. Tastes in moving pictures as in governments are likely to be decided by artillery duels a hundred miles across the frontier.

The lights flashed up and we got a glimpse of what our three francs had brought us to.

We were standing in a sort of low balcony along one side of a rectangular room. The screen was stretched across the corner opposite the door. On the main floor the seating-facilities consisted of two benches and perhaps fifty straight-backed wooden chairs. A bar with china fixtures, similar to the one in the room through which we had passed, occupied one end of the room, leading one to suspect that this place had not always been a temple of the cinema.

It is not altogether correct to infer that all of this was immediately visible. For all the brilliance of perhaps a dozen incandescent lamps, we had been in the place some minutes before the salient features of it began to impress themselves upon us. The atmosphere was a vast, well-nigh impenetrable cloud of tobacco smoke.

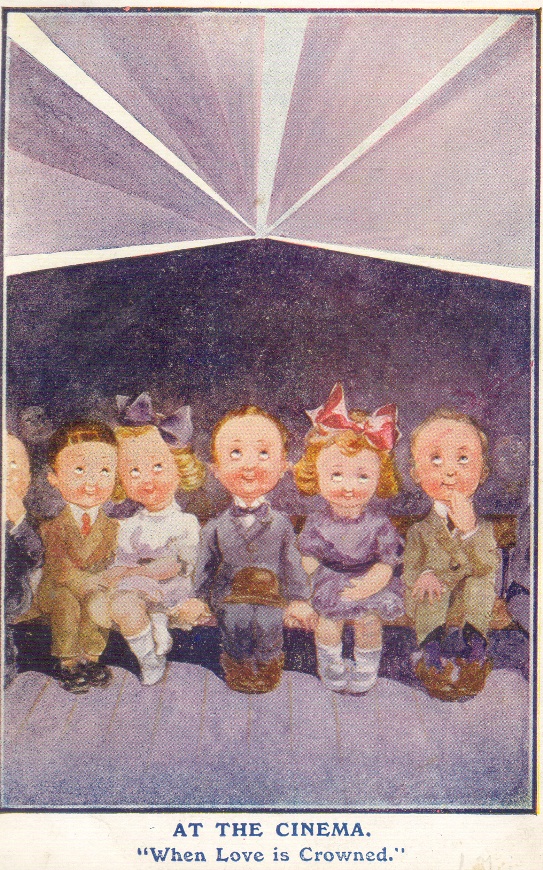

We found some seats on a bench at the edge of the balcony and disposed ourselves as best we could. The seats in the pit were occupied mostly by children, little girls about ten years old predominating, with a scattering representation of adults. There was an incessant chattering among the youthful patrons, but no functionary in brass buttons came to interrupt them. There seemed to be any number of little black velvet bonnets in the house, some of them trimmed with pink ribbons, some with blue. A minority of small boys in the round cap of the French-marine type assisted in the manufacture of the din, making one notable contribution in the way of a fist fight before we had been in the place five minutes.

I took advantage of the wait between pictures to look at the red program.

The information conveyed in three assorted languages was little short of astonishing. I learned from the English part of it that there would be:

MOVING PICTURES

at Sunday

In the Afternoon at 3 o’Clock

at night 8 o’clock

at SATURDAY and MONDAY

at Evening at 8 o’clockECLAIR JOURNAL

The Kaiser and President WilsonSherlock Holmes

the greatest american detektiv in:

ON THE LINE OF THE FOUR

In 2 PartsCasimir and the Fireman

Humorist in 1 actTHE BLACK CAPTAIN

Far West Dramaand

Flottes Orchester

1 Platz, 3 Fr.; 2 Platz, 2 Fr.; 3 Platz, 1.50 Fr.

And there were further words in German to the effect that children would be admitted to matinee performances at half-price.

It was in the French part of the bill of fare, however, that the true eloquence of the cinema management showed itself. To begin with, the pedigree of the films was presented to the attention of the public. To a stranger in the land, an itinerant who might be interested in the English program, a film would be merely a film. It was in the nature of the tourist to take what one gave him and pay well for the privilege. The native sons, how-ever, must be advised of the quality of the product that they were asked to purchase. Hence they were told with-out preliminary waste of space upon the topics of the pictures that the films were from Paris. To cinema-fanciers who for four long years had gazed upon flickerings from Prussia, the name Paris probably carried a magic appeal.

The kaiser and President Wilson, on this side of the dictionary, were passed over in small type. So was Sherlock Holmes, “the greatest american detektiv.” But Le Capitaine Noir came in for a great deal of publicity of the circus-poster variety.

This feature was billed as “A great drama of adventure in four acts and a prologue,—a number of sensational scenes: Chases on the Plains; the Ambush; The Mark of Fire; The Escape; The Burning Granary.” One would be a sensation-seeker indeed who could wish for more excitement for his three francs.

I suspected from the first that “On the Line of the Four,” however much it might promise as a war picture, was very likely our old friend and neighbor “The Sign of the Four,” and so it was.

The original nationality of the piece was a doubtful matter. There was hardly enough of it left to give one a consecutive idea of the plot, and the French captions were so worn that little was to be gained from them. It may have been an American film of that era when there were no stars. At any rate, no latter-day favorites appeared in it. It may have been English. Certain elements in the “locations” suggested England forcibly. But whatever its pedigree, its days of usefulness were nearly done.

The Anglo Saxons in the house, to whom the name Sherlock Holmes was a sufficient guaranty of story action and plot, could not get very far with the titles in French. Those who had mastered enough of the language to surmount this difficulty were certain to become hopelessly muddled in the aimless mixing of scenes that seemed to be the result of many years of “cut and patch.”

The children, however, enjoyed the piece just as young America used to enjoy pictures of fleeting express-trains and dashing fire-engines. The doings of the “greatest american detektiv” as marvels of mental acrobatics appealed to them not a whit. But the doings of the East Indian murderer with his shiny black hide, his wicked eye, and his deadly poisoned dart, were truly delightful.

“Der Schwarze,” as they nicknamed him, could not so much as twist a finger from the moment of his first entrance into the drama until the last ghostly glimmer of Dr. Watson’s romance, without arousing an excited hum throughout the house.

The children wildly applauded his capture and cast upon him any number of maledictions in German and French. They commented volubly upon the flashes supposed to show the theft of the rajah’s jewels in India, and stood up in their seats and yelled when the Black was shown in the act of shooting the fatal dart.

They may have gathered something from the torn film to give them an inkling of the motive of revenge that underlay the murderer’s desire to kill. But from their point of view the motives were immaterial. This Indian person was downright murderous. They had seen him in his deadly but interesting pastime of shooting poisoned arrows,—truly a reprobate. And he was chased and caught and turned over to the gendarmes. Served him right! A very excellent picture!

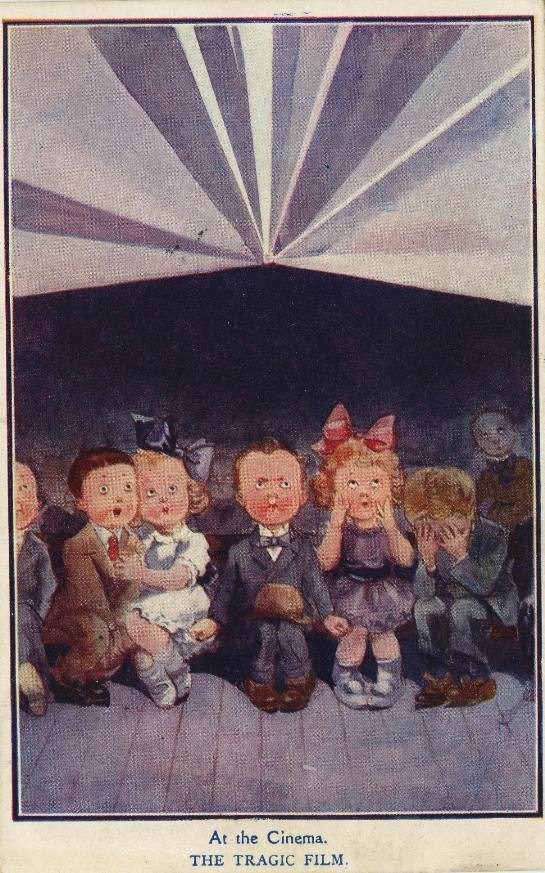

We learned, too, that the burghers are a romantic people, as befits their surroundings and traditions. They sighed with sympathy when Dr. Watson breathed words of love into the ear of Mary Marston. They murmured approbation when he put his protecting arm about her in that tense moment just before the discovery of the murder; and they howled with startling intensity, adults and infants alike, when the film snapped off short before the climacteric embrace.

The flottes Orchester was the greatest disappointment in the show. It failed to arrive. A small boy with a typical toy harmonica attempted to remedy the deficiency with plaintive notes that filtered unpleasantly through the other noises.

Between films we got another glimpse of our surroundings.

On the wall near the entrance there were yellowing posters of past feature pictures. They were uniformly German and slipshod, the type one used to see before the nickelodeons of a decade ago. One bore the title “Schwer Gepruft” and showed a Prussian villain staring through a brick wall at a blonde girl playing a piano. Another was a sketch in black and white advertising “Der Gestreifte Domino.” The domino was a doleful-looking person whose activities in the film were not described.

In a far corner was a French advertisement for “Deux Ames de Poupée” played by a “notable cast of three” from some theater in Paris. None of these posters looked new, though the theater undoubtedly had been in use during the German occupation. This led us to believe that any films shown in Luxemburg since the autumn of 1914 must have been worn-out stock, hastily salvaged from the waste-heaps to struggle through four years more of life. The conviction remained with us even after the proprietor had assured us that a Copenhagen distributor had given him a choice of first-run productions during the entire period in which the French supply was unavailable.

The adventures of the Black Captain started inauspiciously. The picture was improperly framed during the first few seconds and the lower half appeared on top and the upper half below, as is the universal custom with unframed cinema.

Immediately the ensemble of spectators yelled out, “Hoch!” with a unanimity that shook the ancient rafters.

The film presently slid into its proper groove, and, save for the normal clatter of the children and their parents, quiet was restored. To a visitor the incident was worthy of note as something odd in the system of communication between the house and the management.

It has its points of superiority over the good old American custom of kicking chair backs, whistling, and foot-stamping, as any one will admit. It is no easier on the ears, perhaps, but its effect is quicker. No operator, not even a German operator, can stand the concerted shrieking of half a hundred excited youngsters.

The prologue of this “adventurous picture”—the words are those of the opening caption—extended through about a reel and a half of the total four. Whether out of deference to an artistic color scheme or not we cannot say, but Monsieur Violet, a French actor, was cast in the role of Capitaine Black. The girl in the piece, whose name we have forgotten, and the deep-dyed villain who stole her love, were the only important figures in the story aside from the colorful captain. The lady appeared to be at least as old as the film, which was old enough, and had a sharp nose a trifle too long for her own good. But she suited the spectators in the seventy-five centime seats, and from that time forward we knew that the picture was going to be well received.

Monsieur Violet, as the Duke of Chablis, is in love with Miss Arabella, a circus rider. He marries her, much to the grief of his best friend,—another duke whom, for the purpose of identification, we shall call the Duke of Ornans.

After the inevitable elopement of Lady Arabella with the Duke of Ornans, Monsieur Violet meets the wrecker of his home and kills him in a duel. The two former friends become reconciled in the death scene and the wrecker, after the fashion of wreckers, warns the wronged husband to beware of the woman who is “the cause of it all.”

The husband encounters the faithless wife as he is carrying the body of the betrayer into the chateau whither the erring couple have fled. It is a strong scene in many ways, about as well acted as it is original, with many flashes of raised fists and kneeling supplication. Here the prologue ends in a hysterical burst of recrimination and anathema.

None of this was in keeping with the moral code of Luxemburg, where marriages are pretty sure to be permanent. But it was romantic, passionate, bombastic, and was applauded with shouts.

The next scene showed the arrival in America of the Lady Arabella, who had journeyed into the Far West to claim an estate left her by the traitorous friend.

And it was truly a wonderful America in which she found herself.

An official with a uniform like that of a milkman carried her suit-cases from an unfamiliar railway platform to a stage-coach. The coach was a long, slim thing like the French army’s “Fourgon, Mile. 1887.” It was drawn by three horses and greatly resembled the American vehicle it was supposed to represent in that both of them had wheels.

In the meantime the Duke of Chablis had become the chief of a band of Mexican outlaws, and, under the name of the Black Captain, was spreading terror along the borders of the United States,—a splendid revenge for a husband whose home had been wrecked, but a bit hard on Texas or New Mexico.

The Luxemburgers could not understand this idea of vengeance. But theirs not to question why. It was action they wanted and action they got.

The bandits attacked the stage-coach.

Artful bandits they were. They kept themselves informed of the movements of the coach by a clever system of espionage. If the girl had only noted the dark figure at the corner of the station platform, what excitement she might have saved herself! She would have recognized him at once for a foe. For he was attired in a fedora hat with a feather in it, and even a timid European knows that the Indians who have for their tribal insignia the fedora hat are the most bloodthirsty of all.

Of course there was a battle. It wasn’t a very good battle at first, because both sides failed to show any marksmanship until they warmed up to their work. But after about a kilometer of chase things were different. Nearly everybody on both sides dropped dead at once. It was a thrilling climax.

The few passengers left alive clambered out of the coach to permit themselves to be robbed, the Lady Arabella confronting the mysterious Black Captain. And the house actually approached silence. One could have heard an anvil drop, so quiet was that tense moment when he lifted his mask and showed the once trusted but treacherous love, his sneering lips and hate-filled eyes.

He was very deliberate about it,—always the gentleman, the duke, outlaw or not. He was so deliberate that he turned his back upon her momentarily and she escaped.

The outlaws held a brief conference and leaped to horse in pursuit as she sped down the glistening road.

The house had a wild time about it.

American moving-picture men used to hold long news-paper debates concerning the propriety of applauding the silent drama. But I have never yet seen a decision relative to the etiquette of starting a riot at a thrilling moment. The young Luxemburgers stood up in their chairs and howled.

The people of the grand duchy are not so volatile as those of France. Superficially they bear a closer resemblance to their German neighbors. But they stand proved a race apart to one who has ever seen them at the cinema. They feel deeply and express themselves energetically regardless of time or place. They leap from stolidity to intense animation with the quickness of a flash of light.

The girl outdistanced all the bandits save the Black Captain, and this relentless pursuer chased her through a few Italian villas and other little-known parts of Mexico. Just as he caught up with her the film broke and the cheering spectators subsided with a deep sigh.

That gave us a chance to escape without being trampled upon and we made the best of our opportunity.

It was snowing when we reached the street. The braided gendarme stood as we had left him, his silver epaulets glistening like diamonds with the frost.

Comments: Robert Joseph Casey (1890-1962) was an American journalist and soldier, who served during the First World War and went on to write several books on his travels around the world. The Land of Haunted Castles documents a tour of Luxembourg not long after the war, with this visit to a film show taking place in the town of Ettleburck. The Sherlock Holmes film referred to is unclear but it may have been the American film Sherlock Holmes Solves The Sign of Four (1913), produced by Thanhouser and featuring Harry Benham as Holmes. The French film may be Le capitaine noire (1917), though this did not feature a M. Violet in the cast. However it was produced by the French Éclair company, as was the Éclair Journal newsreel and the ‘Casimir’ series of comedies listed on the programme. There was an Éclair series of Sherlock Holmes films, but none was based on ‘The Sign of the Four’.

Links: Copy at Hathi Trust