Source: Eric Sykes, If I Don’t Write It, Nobody Will (London: Fourth Estate, 2005), pp. 78-80

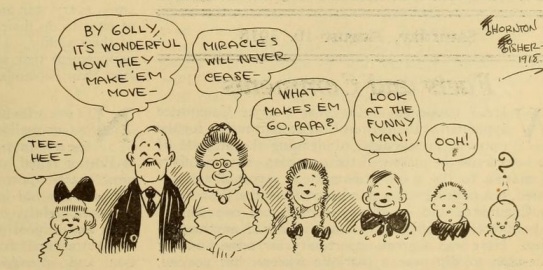

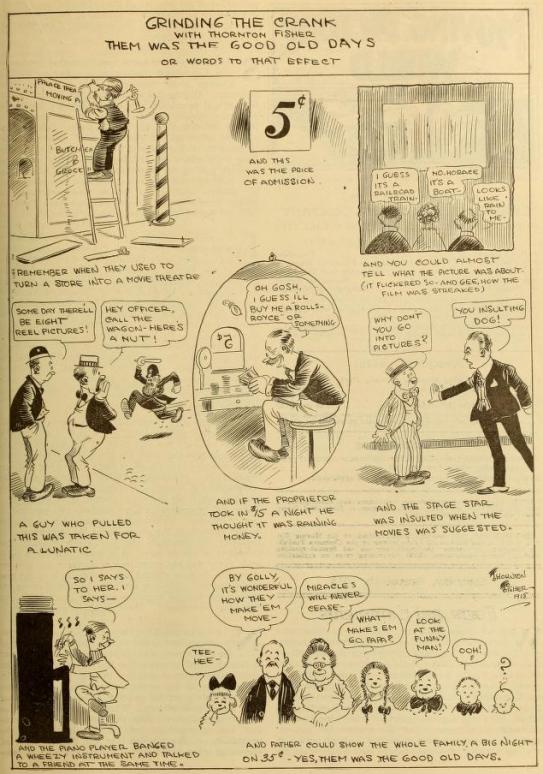

Text: If the world was not exactly our oyster, it was most definitely our winkle. Our main Saturday night attraction was the Gaumont cinema at the end of Union Street. As for the films, the question we first asked ourselves was, ‘Is it a talkie?’and the second ‘Is it in colour?’ This didn’t bother us a bit; it was Saturday night, hey, lads, hey and the devil take the hindmost.

The Gaumont cinema was a large, luxurious emporium showing the latest films and up-to-date news, not forgetting Arthur Pules at the mighty Wurlitzer. For many Oldhamers the perfect panacea for the end of a stressful working week was a Saturday night at the pictures. Just relaxing into the armchair-like seats was an experience to savour. Uniformed usherettes busily showed patrons to their seats; one usherette stood against the orchestra pit, facing the audience with a smile as she sold crisps, peanuts, chocolates and soft drinks from a tray strapped round her shoulders; another usherette patrolled the aisles, selling various brands of cigarettes and matches from a similar tray. There was a general feeling of content in the audience, excitement slowly rising under subdued babble of conversation. The audience were the same people who had gone off to work during the week in overalls, dustcoats, ragged clothing and slightly better garb for office workers, but at the Gaumont cinema they had all, without exception, dressed up for the occasion. All the man wore collars and ties and the ladies decent frocks and in many cases hats as well. What a turnaround from my dear-old Imperial days; no running up and down the aisles chasing each other and certainly no whistling, booing or throwing orange peel at the screen during the sloppy kissing bits. In all fairness, though, I must add that it was only at the Saturday morning shows and we were children enjoying a few moments not under supervision or parental guidance. In fact when I was old enough to go to the Imperial for the evening films the audience even then dressed up and enjoyed the films in an adult fashion.

Back to the sublime at the Gaumont cinema; as the lights went down, so did the level of conversation. A spotlight hit the centre of the orchestra pit and slowly, like Aphrodite rising from the waves, the balding head of Arthur Pules would appear as he played his signature on the mighty Wurlitzer. He was a portly figure in immaculate white tie and tails, hands fluttering over the keys and shiny black pumps dancing over the pedals as he rose into full view, head swivelling from side to side, smiling and nodding to acknowledge the applause; but for all his splendid sartorial elegance, having his back to the audience was unfortunate as the relentless spotlight picked out the shape of his corsets. Regular patrons awaited this moment with glee, judging by the sniggers and pointing fingers. We were no exception; having all this pomp and circumstance brought down by the shape of a common pair of corsets on a man was always a good start to the evening’s entertainment.

At this point the words of a popular melody would flash on to the screen – for instance, the ‘in’ song of the day, ‘It Happened on the Beach at Bali Bali’ – and, after a frilly arpeggio to give some of the audience time to put their glasses on, a little ball of light settled on the first word of the song. In this case the first word was ‘It’; then it bounced onto ‘Happened’; then it made three quick hops over ‘on the Beach at’; then it slowed down for ‘Bali Bali’. The women sang with gusto and the men just smiled and nodded.

Happily this musical interlude didn’t last too long. Arthur Pules, the organist, was lured back into his pit of darkness and the curtains opened on the big wide screen. The films at the Gaumont were a great improvement on the grainy pictures at the Imperial, and so they should have been: after all, the film industry had made great strides in the eight years since John and I had sat in the pennies, dry mouthed as the shadow moved across the wall to clobber one of the unsuspecting actors.

After two hours of heavy sighs and wet eyes ‘The End’ appeared on the screen and the lights in the auditorium came up, bringing us all to our feet as the drum roll eased into the National Anthem … no talking, no fidgeting, simply a mark of respect for our King and Queen.

Comments: Eric Sykes (1923-2012) was a British comic actor and writer, who wrote and performed widely over many years for film, television and radio, including the 1970s sitcom Sykes. He was born and raised in Oldham, Lancashire, and at the time of this recollection was in his mid-teens, having left school aged fourteen. John was his half-brother. The Gaumont cinema in Oldham was at corner the King Street and Union Street, having been re-built as a cinema in 1937 out of an earlier theatre.