Source: ‘College senior, a girl of 22 years, of native white parentage’, quoted in Herbert Blumer, Movies and Conduct (New York: Macmillan, 1933), pp. 213-217

Text: Considerably influenced by the gospel of H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan, I have for the past few years held the complacent attitude that “the movies were made for morons,” that they were an inferior order of entertainment, and that I was possessed of an intellect decidedly too keen to be swayed by such a low order of art. But as I detach myself from this groundless generalization and consider objectively my motion picture experiences, it appears that, on the contrary, I am at least temporarily very acutely affected.

The movies could not have wielded a very great or enduring influence over me, however, for the reason that I have never been a chronic devotee. All the eighteen years of my life I have lived in a small town whose only picture palace was a small, dark, ill-ventilated hole, frequented by every type of person. As I was rather frail, and an only child, my mother regularly discouraged attendance there; I do not recall ever seeing a movie unaccompanied by one of my parents until I was eleven years old. The theater was called the Critic, a name indicative of the types of shows presented to attract the ardent Baptist population.

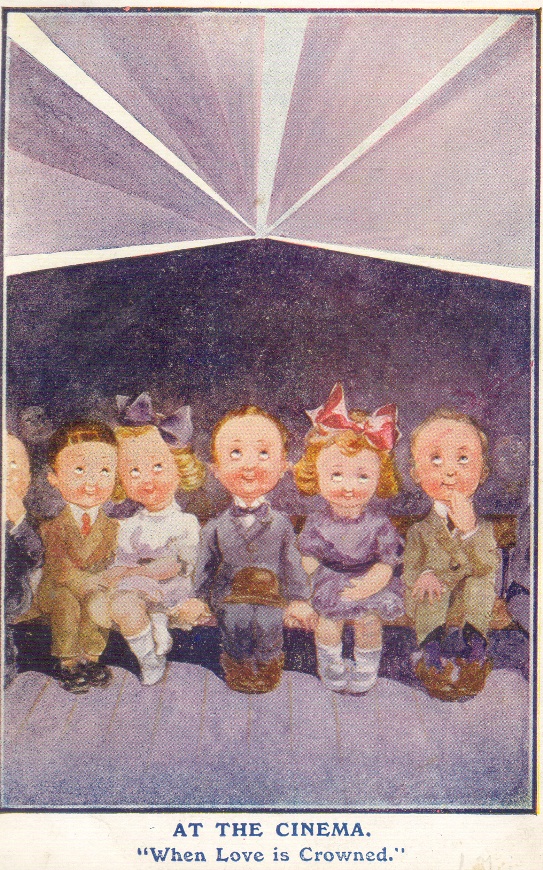

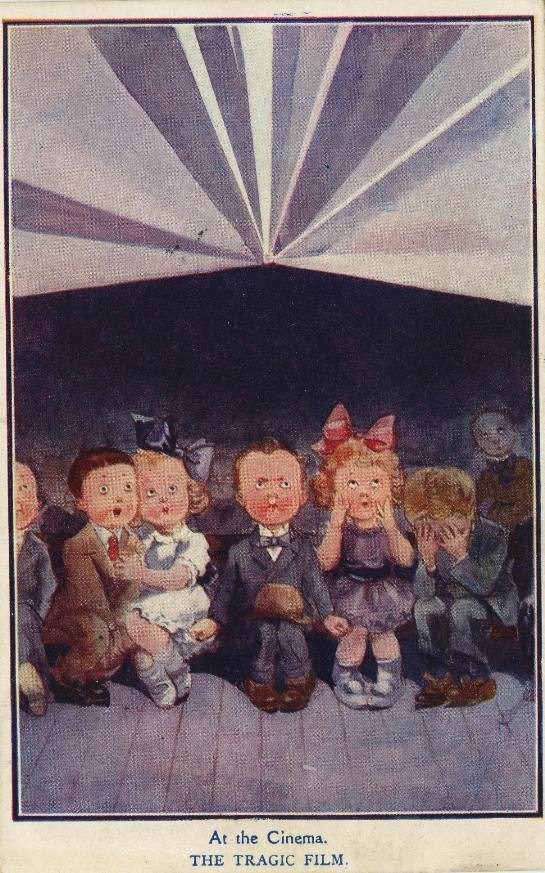

My first recollection of a movie is still a very vivid one. I could not have been more than five at the time, when Mother took me to a matinee to see Charlie Chaplin. We arrived early, just in the middle of a “serial,” which was shown in weekly installments. It was called “The Claw,” and revolved about a villainous character whose right hand was replaced by an iron hook. I can still see this claw reaching out from behind a bridge to grab the heroine. Even the following antics of the famous comedian failed to soften my terrified impressions, and for weeks after I slept with the light on at night and peered carefully under the bed each morning before setting foot on the floor.

I also remember seeing at a later date other “serials” in one of which a mother and her child, shipwrecked, drifted about the Atlantic Ocean clinging to a log, while the struggling husband and father drowned before their eyes; and in the other of which occurred a forest fire. All my earliest impressions were those of fear – very real and vivid.

A little later on, however, between the ages of about six and nine, the movies began to work their way into our play. At one period, our favorite game was “Sandstorm,” an idea derived directly from some desert picture now forgotten. The two little boys with whom I played and I would hide in our caravan, the davenport, and watch the storm sweep over the horizon. When it reached us, we would battle our way through it, eventually to fall prostrate in the middle of the room, where we would lie until the storm blew over. Then we would get up and start the game over.

Another popular pastime, which was undoubtedly affected by certain “Western” pictures was “Cowboy.” My father had at one time lived on a coffee plantation in Mexico and owned and provided us with all the necessary regalia – ten-gallon hats, spurs, ‘kerchiefs, and holsters. The pistols which went with the outfit we were not allowed to have, but carried instead carved wooden guns. Stories of Father’s own (fictitious?) experiences were combined with movie scenarios to form what was for two years our great game. I do not recall any specific instances of our imitating the two-reelers, but I do know that Father obtained and autographed for us greatly cherished photographs of the inimitable William S. Hart.

After I entered school, my tastes changed rapidly from the hairbreadth, wild and woolly Westerners and slap-stick comedies to more sentimental forms. Until the time I entered Junior High, I was interested in the actresses, the heroines. I preferred them sweet, blonde, and fluffy – everything that I was not. I doted on misty close-ups of tear-streamed faces. In the sixth grade, my best friend and I were constantly imitating Mary Miles Minter and Mary Pickford, respectively. Later on I became, in turn, Alice Calhoun and Constance Talmadge, but my friend remained true to her first crush. In classes we wrote notes to each other, and signed them “Mary,” “Alice,” or whatever names we had at the time adopted.

After the seventh grade, however, my attentions again shifted, this time to the male actors. I had become boy-conscious, and, affecting an utter disdain toward all boys of my acquaintance, I took delight in the handsome and heroic men of the screen. I liked nearly all of them, as long as they were neither too old nor too paternal (like Thomas Meighan), but I especially favored Charles Ray, Harrison Ford, and, above all, Wallace Reid. He epitomized all I thought young manhood should be clean, good-looking, daring, and debonair. All the girls of my age and most of the boys liked him. We saw such pictures as “Clarence,” “The Affairs of Anatole,” and “Mr. Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford.”

As a young high-school student, I attended the movies largely for the love scenes. Although I never admitted it to my best friend, the most enjoyable part of the entire picture was inevitably the final embrace and fade-out. I always put myself in the place of the heroine. If the hero was some man by whom I should enjoy being kissed (as he invariably was), my evening was a success and I went home in an elated, dreamy frame of mind, my heart beating rather fast and my usually pale cheeks brilliantly flushed. I used to look in the mirror somewhat admiringly and try to imagine Wallace Reid or John Barrymore or Richard Barthelmess kissing that face! It seems ridiculous if not disgusting now, but until my Senior year this was the closest I came to Romance. And then I fell in love with a boy that looked remarkably like

Dick Barthelmess.

I liked my movies pure Romance: beautiful heroines in distress, handsome gallants in love, gorgeous costumes, and happy endings. “When Knighthood Was in Flower,” “Robin Hood,” “Beau Brummel,” and “Monsieur Beaucaire” were favorites, although as a rule I didn’t like screen versions of books I had read and loved. (“The Three Musketeers” was an example of an adored book grossly insulted.) In a life which was monotonous with all the placidity of a Baptist small town, these movies and books were about all the excitement one could enjoy.

I never liked pictures with a moral, unless it was so subtly expressed that I was unaware of its preaching. Such movies as “The Ten Commandments,” and more recently the “King of Kings,” impressed me as gorgeous spectacles, but too flagrant in their moralizing, so that in parts I was bored to the point of antagonism. A renovated production of “Ten Nights in a Barroom” was so bad it bordered on a screamingly funny burlesque. Just recently, however, I saw “White Shadows in the South Seas,” and was surprised to discover how deeply I was affected by the propaganda.

Over-sexed plays were always more or less repulsive. I remember especially “Flesh and the Devil” with the Garbo-Gilbert combination and an older one starring Gloria Swanson and Valentino. I liked neither. The former embarrassed and the latter bored me.

I have always been unrestrained in my emotions at a motion picture. My uncontrollable weeping at sad movies has been a never-ending source of mortification. I recall first shedding tears over the fate of some deserted water-baby when I was about eight years old, and I have wept consistently and unfailingly ever since, from “Penrod and Sam” to “Beau Geste.” The latter, which I liked as well as any picture I have ever seen, caused actual sobbing both times I saw it. I weep at scenes in which others can see no pathos whatsoever. Recently I have refused to see a half-dozen notably sad shows because of their distressing effects.

I do not believe the movies have ever stimulated me to a real thought, as books have done. Neither have they influenced me on questions of morals, of right and wrong. They have given me a more or less fluctuating standard of the ideal man – in general, the good-looking, dreamy, boyish type – and the kind of lover he must be – sincere, thoughtful, and tender. They have given me my ideas of luxury – sunken baths, silken chaises-lounges, arrays of servants and powerful motors; of historical background – medieval castles, old Egyptian palaces, gay Courts; and of geographical settings – the moonlit water framed in palms of the South Seas, the snow fields of the far North, the Sahara, the French Riviera, and numerous others. I suppose they have from time to time influenced my conception of myself; although I was not aware of this until recently when I saw “A Woman of Affairs,” the film version of Michael Arlen’s “Green Hat.” For days after I was consciously striving to be the “Gallant Lady”; to face a petty world squarely and uncomplainingly; to see things with her broad, sophisticated vision; even to walk and to smoke with her serene nonchalance. I, too, wished to be a gallant lady.

On the whole, I doubt if the movies have wielded much of an influence on my life; not because they were incapable of it, but because they have had too little opportunity. In my youth, my family discouraged attendance at the local cinema, and as I grew older, I formed other interests. Since the first of October, I have seen no more than ten pictures. Two of these impressed me immensely; three of them I could not sit through. Last year I used to go mainly to hear the organ music, but with the advent of the Vitaphone, this attraction is dispensed with. I dislike the stage shows presented at the leading theaters, and also the “talkies.” I usually attend a movie for rest and relaxation, and a bellowing, hollow voice or a raucous vaudeville act does not add to my pleasure. I like my movies unadulterated, silent, and far-between.

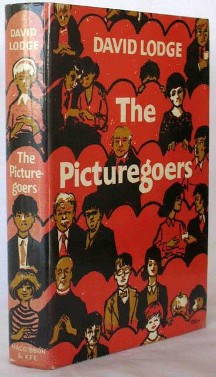

Comments: American sociologist Herbert Blumer’s Movies and Conduct presents twelve studies of the influence of motion pictures upon the young, made by the Committee on Educational Research of the Payne Fund, at the request of the National Committee for the Study of Social Values in Motion Pictures. The study solicited autobiographical essays, mostly from undergraduate students of the University of Chicago, and presented extracts from this evidence in the text. This extract comes from Appendix C, ‘Typical Examples of the Longer Motion Picture Autobiographies’.

Links: Copy at Internet Archive