Source: Mrs Robert Henrey, The little Madeleine: the autobiography of a young French girl (New York: Dutton, 1953), pp. 199-200, 204-205

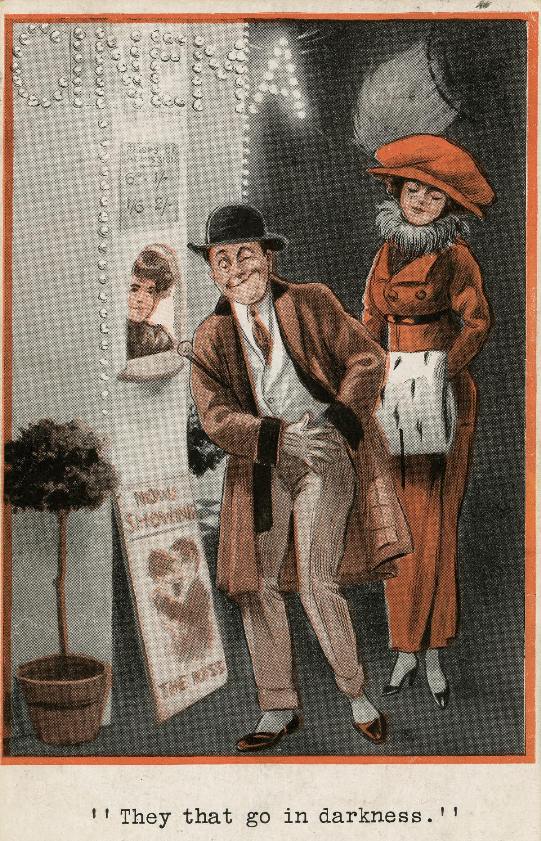

Text: Mme Maurer, grateful and generous, found a charming way to say thank you. Immediately after lunch on my half-holiday she, my mother, and I would go to the cinema in the Avenue de Clichy, where the programme included a film in several episodes, with Pearl White, and a Max Linder comedy. The programme started at two, and as soon as I heard the bell announcing the approach of the great moment my excitement was immense. Pathé Journal began with a flickering news-reel. Weary soldiers in long files marched down the lines. Lloyd George and Clemenceau danced across the screen with unbelievable speed. King George V and his good-looking son, the Prince of Wales, shook hands with soldiers and climbed over trenches and barbed wire. The cinema seemed to soak all these famous men and incidents with an oblique and incessant rain.

My mother found in these visits to the cinema her first moments of genuine pleasure. We would discuss what we had seen, thinking all the week about the next episode. A little later the great Gaumont Palace was opened in the Place Clichy. Then it was a different matter. The most famous cabaret singers in Paris were engaged to appear in the intervals, and the auditorium, full of soldiers and officers of every nation, made our hearts beat with patriotism.

[…]

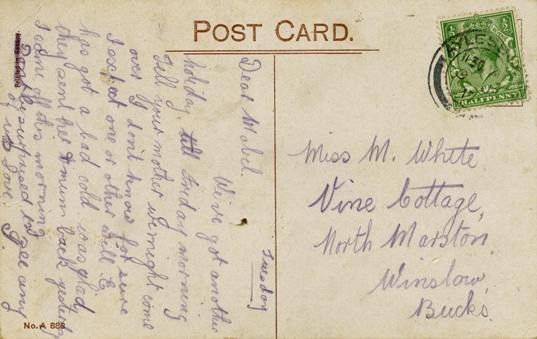

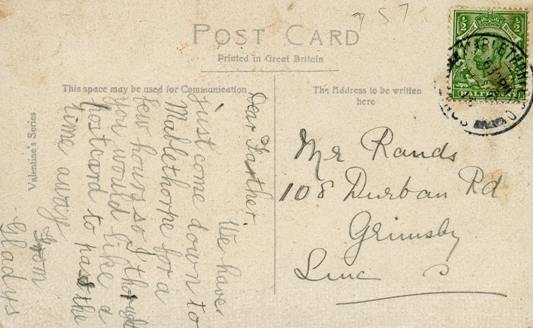

When my father was on a night shift my mother, Marguerite Rosier (we had now forgiven her for running away from the man with the knife), and I went to a cheap cinema in the Boulevard National, arriving half an hour before the performance started, to be sure of having the best seats.

Our cinema smelt of garlic and peppermint drops. Palm-trees stood on either side of the stage, their branches casting uneven shadows on the white screen like giant spiders. Excitedly we waited. In spite of our love for Pearl White we had not quite cured ourselves of thinking of the cinema in terms of the age-old theatre, and we had gone instinctively to the front of the stalls where, after a while, we would see appear from behind a curtain a little hunchback woman with a big white head surmounted by a number of diamanté spangled combs. She would slip her rheumatic knees under an upright piano and begin a Strauss waltz. The apache boys from the fortifications who were here in large numbers whistled the accompaniment, while putting an arm round the shoulder of a girl, getting into position to unbutton the blouse and fondle her breasts. These were the girls who worked for them as prostitutes on the outer zone, drawing men with alluring gestures, like Circes, near to the wall where the apache lay in waiting with his knife. All the boys wore their caps and sometimes their red scarves. A few moments later came a small dark man holding a violin case tightly under his arm, and as he made his way towards the hunchback his journey was followed by loud whistles and exclamations of ‘Hurry up, maestro! You’re late, brother! Let’s go and sleep with his wife while he scratches a tune on his fiddle!’ The fiddler, pale and without any sign of fluster, removed a black hat, placing it carefully on the edge of a chair, folded his overcoat, took up the hat which he would then place on top of the folded overcoat, and delicately brush the dandruff from his narrow shoulders. At last he opened the case, holding the violin under an arm whilst he put a handkerchief under his chin. The audience invariably cried out: ‘The little old man is going to weep!’ Then dolefully: ‘Don’t worry, daddy, you’ll see her again, your girl friend!’ Now at last, with a sign of his bow to the hunchback, he would begin to play. The lights would go out. The screen flickered.

By the time the big film started this chaffing audience was settling down to the charms of Mary Pickford with her blonde curls. The love-story was getting the better of these boys and girls from the fortifications who, for all their naughtiness, were just sentimental children. At this magnificent moment, after all the fatigues of the long day, after school, after queueing, after playing in the street, exhausted, I fell fast asleep on my mother’s shoulder! This happened every time we went to the cinema. Before setting out in the evening I would say: ‘If I go to sleep you will wake me up, won’t you, mother?’ She promised. Indeed she did wake me, but after rubbing the sand out of my eyes and trying to unravel the plot, I fell asleep again, and my mother, transported to a land of make-believe, was far too interested in the romance to keep on pinching my arm. I would sulk on the way home, and childishly threaten to tell my father where we had been. My mother answered patiently: ‘To-morrow I will describe the whole episode to you while you are sewing, and next time you really must try to keep awake!’

Comments: Madeleine Henrey (1906-2004), who mostly published as Mrs Robert Henrey, was a French author of popular memoirs. Her son, Bobby Henrey, played the child lead in the film The Fallen Idol (UK 1948). The Gaumont Palace, located at Place Clichy, Paris, opened in December 1907, ahead of Henrey’s First World War period memories. It was the largest cinema in Europe, seating over 6,000.

Links: Copy at Hathi Trust