Source: Alan Bennett, extract from ‘Going to the Pictures’, Untold Stories (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), pp. 466-469 (originally published, in shorter form, as ‘I know what I like, but I’m not sure about art’ in The Independent, 24 May 1995, based on a lecture given at the National Gallery on this date)

Text: Floundering through some unreadable work on art history, I’ve sometimes allowed myself the philistine thought that these intricate expositions, gestures echoing other gestures, one picture calling up another and all underpinned with classical myth … that surely contemporaries could not have had all this at their fingertips or grasp by instinct what we can only attain by painstaking study and explication, and that this is pictures being given what’s been called ‘over meaning’. What made me repent, though, was when I started to think about my childhood and going to a different kind of pictures, the cinema.

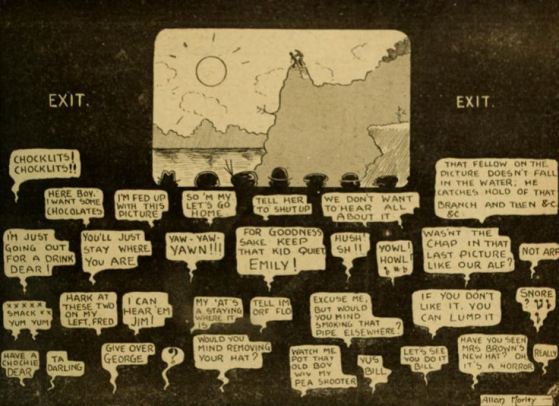

When I was a boy we went to the pictures at least twice a week, as most families did then, regardless of the merits of the film. To me Citizen Kane was more boring but otherwise no different from a film by George Formby, say, or Will Hay. And going to the pictures like this, taking what was on offer week in week out was, I can see now, a sort of education, an induction into the subtle and complicated and not always conventional moral scheme that prevailed in the world of cinema then, and which persisted with very little change until the early sixties.

I’ve been trying recently to write about some of the stock characters of films of that period and I’ll talk about two in particular in the hope that I can relate one sort of pictures to the other.

A regular figure in films of that time was a middle-aged businessman, a pillar of the community, genial, avuncular, with bright white hair, and the older ones among you will know immediately the kind of character I mean if I should you this actor. His name is Thurston Hall, and this is another actor, Edward Arnold. Their names are unimportant but they were at that time instantly recognisable. I certainly knew at the age of eight that as soon as this character or this type of character put in an appearance he was up to no good.

The character speaks:

I am not an elaborate villain, nor is my spirit particularly tormented; crime in my case is not a substitute for art. It is just that my silver hair and general benevolence, invariably supplemented by a double-breasted suit, give me the appearance of an honest man. In the movies honest men do not look like honest men and suave is just another way of saying suspect. Bad men wear good suits; honest men wear raincoats, and so untiring are they in the pursuit of evil that they sometimes forget to shave.

The converse of this character, though he is seldom in the same film, would be the man who has been respectable in himself once but who has made one big mistake in his life – a gun-fighter, say, who has killed an innocent man, a doctor who bungled an operation – and who by virtue of his misdemeanour (and the drink he takes to forget it) has put himself outside society.

Thomas Mitchell was such a doctor in John Ford’s Stagecoach, and though such lost souls are more often come across in westerns they turn turn up in the tropics too, their frequent location the back of beyond.

The character speaks:

In westerns I will generally team up with the tough wise-cracking no-nonsense lasy who runs the saloon, who in her turn, inhabits the audience’s presuppositions about her character. They know that a life spent in incessant and lucrative sexual activity has not dulled her moral perceptions one bit. They remember Jesus had a soft spot for such women, and so do they.

I am frequently a doctor, in particular a doctor who at a crucial turn of events has to be sobered up to deliver the heroine’s baby or to save a child dying of diptheria. Rusty though my skills are, I find they have not entirely deserted me and I am assisted in the operation by my friend the proprietress of the saloon. She is tough and unsqueamish and together we pull the patient through, and having performed a deft tracheotomy my success is signalled when I come downstairs and say, ‘She is sleeping now.’

He concludes:

But though I rise to the occasion as and when the plot requires it, there is never any suggestion that I am going to mend my ways in any permanent fashion. Delivering the baby, flying the plane, shooting the villain … none of this heralds a return to respectability, still less sobriety. I go on much as ever down the path to self-destruction. I know I cannot change so I do not try. A scoundrel but never a villain, I know redemption is not for me. It is this that redeems me.

Now though this analysis may seem a bit drawn out, the point I am making is that the twentieth-century audience had only to see one of these characters on the screen to know instinctively what moral luggage they were carrying, the past they had had, the future they could expect. And this was after, if one includes the silent films, not more than thirty years of going to the pictures. In the sixteenth century the audience or congregation would have been going to the pictures for 500 years at least, so how much more instinctive and instantaneous would their responses have been, how readily and unthinkingly they would have been able to decode their pictures – just as, as a not very precocious child of eight, I could decode mine.

And while it’s not yet true that the films of the thirties and forties would need decoding for a child of the present day, nevertheless that time may come; the period of settled morality and accepted beliefs which produced such films is as much over now as is the set of beliefs and assumptions that produced a painting as complicated and difficult, for us at any rate, as Bronzino’s Allegory of Venus and Cupid.

Comments: Alan Bennett (born 1934) is a British playwright, screenwriter, essayist and actor. Untold Stories is a collection of essays and memoir, including the section entitled ‘Going to the Pictures’, from which this extract comes. The essay was originally a talk given by Bennett in 1995 while he was a Trustee of the National Gallery in London. His childhood was spent in Leeds.

Links: Copy of Bennett’s original talk ‘I know what I like, but I’m not sure about art’ in The Independent